Two Parallel Poles

Contemporary architectural thought in Bosnia and Herzegovina brings about a synthesis of modern and traditional thought which is related to the country’s historical experiences. After First World War Bosnian architects developed a very specific architectural language.

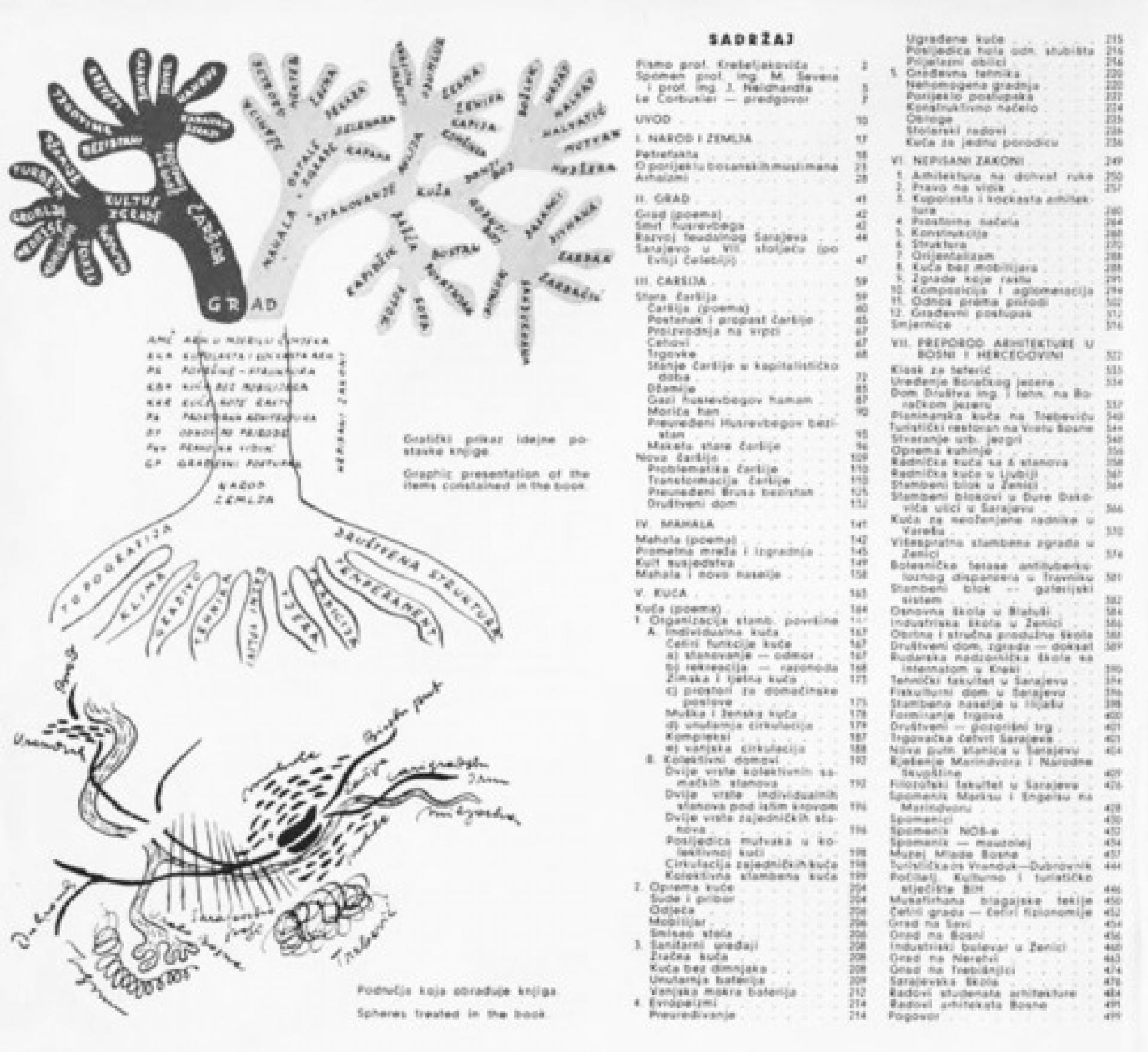

Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity; Index of the book by Neidhardt and Grabrijan, 1957; scan from the book

The foundations of modern tendencies have been inscribed in the work of many local architects, among them H. Baldasar, M. Baylon, J. Finci, D. Grabrijan, L. Kabiljo, R. Kadić, M. Kadić, D. Smiljanić, I. Reis and E. Šamanek which were all trained in Central Europe. Their works promoted an international functionalism which went hand in hand with high social awareness. The meeting of Western and Oriental cultures create a unique approach which respected local cultural traditions and combined it with the postulates and principles of Modernism. [1]

But the most important contribution cme from Juraj Neidhardt, a student of Peter Behrens and Le Corbusier. He arrived in Sarajevo from Zagreb in 1938 and created the theoretical basis for Bosnia’s take on Functionalism. In 1957, together with Dušan Grabrijan, he published a book: Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity.

Grabrijan and Neidhart stress that the architecture of Bosnia “is about two fields of influence – eastern and western – that in this ambiance seek reconciliation. Here we see the intertwining of the western influence with the eastern emotional… Because the opposites attract, it is no coincidence that the Oriental so adores technology and that the Westerner is so attracted by eastern architectures. We want to forge a synthesis of the rational and emotional, we care about harmonious contemporary architecture, which will match new needs, new materials and technologies and will be, in our language, understandable to our people.”[2]

The book is a vision of the modern Bosnian city based on cultural identity and continuity. Urban form is always linked to the social context.[3] As they were both aware of regional architectural movements around the world they wanted to initiate a Yugoslav one based on traditional Balkan architecture. With this book they develop a dictionary of architecture elements and building types for a modern Bosnian city.

In the preface to this book Le Corbusier wrote: „This book has helped me to dispel an ambiguity against which I have been fighting all my life: lazy people always appeal to folklore and copy forms grown out of a definite ethical outlook, a way of life and technique which are very specific, exactly defined and in most cases, thoroughly out of date. (…) There is still another method of continuity- a continuity of spirit and continuity of evolution, including also revolutions that may mark the way. (…) MM. Grabrijan and Neidhardt have felt all this. The extraordinarily copious book they are publishing needs no commentary. These pages will eloquently speak of their sentiments, their technique, their aesthetics etc. For me personally, who have visited Yugoslavia forty years ago and loved its landscape, its houses and its people, it has been a great pleasure to find in this book by MM. Grabrijan and Neidhardt the modern spirit of the world harmoniously united with the things I had retained in a pleasant memory.“[4]

Time period from late 60s to mid- 80s presents a mature contemporary architecture production in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In that period Sarajevo Architectural School was established, that has been characterized by existing of two parallel pole of architectural thoughts and approaches. Institutional generation of architects which present the first pole (A. Džuvić, E. Jahić, M. Ovadija and A. Polić) were profiled to develop regional expression with their distinctive contemporary artistic expression. The second pole is more internationally oriented and merely manifested by public buildings (I.Štraus, B. Bulić, D. Đapa, Z. Janković, M. Kušan, H. Salihović, H. Muhasilović, M. GVozden, B. Krupjel, at al.) Specific place is occupied by Zlatko Ugljen with his research approach towards a new discourse of multilayered reinterpretation of space.

The principal symbolic elements of Šerafudin White Mosque by Zlatko Ugljen have a fresh folk art character. The Aga Khan Award for Architecture jury found it “full of originality and innovation (though with an undeniable debt to Ronchamp), laden with the architect’s thought and spirit, shared richly with the community, and connecting with the future and the past”.

Ugljen Ademović, Turkusić, Ibrišimbegović (2012) stress that varying local sociopolitical constellations cause change in the appearance of the urban context thus integrating its concrete intentions into emerging architecture. This is most visible in small countries in which transitional processes are still very much present. “The aforementioned transition present in Bosnia and Herzegovina has marked transition from social to private ownership in all segments of life and also marked the space and its architectural articulation.”[5]

International University of Sarajevo as a part of the first tendency in the construction of Bosnia and Herzegovina.| photo via Skyscrapercity

Authors single out three current tendencies in the construction of redefining cultural identity of Bosnia and Herzegovina: “The first is political-ideological oriented and starts from primordial notions of identity construction- while rejecting modern heritage or valorization of the socialist period architecture. The aim is to create a homogeneous cultural identity as an element of social stability and a sense of belonging in the transition process. So constructed cultural identity does not really happen to be neither evolutionary nor conservative but fake, artificial and passive. Second tendency is based on a market-oriented relationship of architecture and society, which unfortunately does not attempt any innovative or even neutral architectural forms that could contribute to the cultural context. On the contrary, visually dominant and spectacular aesthetics of the architectural expression characterize this tendency. In the short term it creates a whole new identity, according to the recipe of generic architecture that ignores the existing cultural values. While on the long term, if there is no rejection of such an identity as an old and already seen, it becomes a nuisance and intrigue. Both are aimed at creating a new identity, first by uncritically and selectively creating architectural collage that is a carrier of eligible cultural values, and the other uncritically and indiscriminately appropriates global trends in architecture.

The third tendency, starting from the value of the truth that is found continuously, in regenerating role of culture through the recognition and preservation of the evolutionary basis for the promotion of cultural diversity, is at least present. One reason for this situation is the fact that this tendency is the most difficult one.“ [6] They stress that this process should engage socially responsible role of architects, which can be realized through an educational process and research.

Avaz Twis Tower in city centre of Sarajevo is an example of the second tendency | Photo via Panoramio

Through the example of the building of the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, built in 1963 Ugljen Ademović, Turkusić, Ibrišimbegović (2012) relate directly to the needs and ways of redefining cultural identity intertwine, as well as the role of architecture in this complex process. “Historical Museum by the period of its creation, in the context of the historical development of Bosnian society, belongs to the period of social transition-when the society, after the World War II, the capitalist system of monarchy exceeded into the system of socialist workers’ self-government within the former Yugoslavia. From the architectural point of doctrine, it is a period in which the creative forces of modernism were already weakened by the functionalist dogma of the (post)industrial society.”[7] Characteristic of this architecture is its specific position within the city’s linear structure, where it works as a joint, a natural link between the historic center and the modern city zone, between the old and the new. On of the author of the building Magaš said, they made a memorial and if they’re lucky, it will remain a monument to a time and to the people to whom it is dedicated. Author believes that if we create an architecture that does not match either our time or function, or the characterization of the construction site, it then gets out of the domain of truth.[8]

Museum is today neglected and ignored as an architectural monument and as cultural and educational institutions. It exists in very poor physical condition, which is a result of the lack of political decisiveness regarding maintenance of the heritage of modernist architecture. Thesis that architecture as a testimony on creativity of humans here falls. “The truth is what was, what is valuable, what we found, which creates our memory, culture, identity and wealth. Without that there is no truth, otherwise there is no identity, no culture, no space, form, history, tradition, that tells the truth of human creative works. And without that truth there is no need for positive, for r-evolutionary, that each local community progressively leads to the progress.”[9]

[1] Ugljen Ademović and Turkušić: Unfinished Modernization- Between Utopia And Pragmatism; Sinteza modernog i tradicionalnog u Bosni; edited by Mrduljaš, Kulić, UHA/CCA, 2012

[2] Neidhardt and Grabrijan: Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity; DZS, 1957, p.14.

[3] Kulić, Mrduljaš, Thaler: Modernism in-between, The Mediatory Architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia; Jovis, 2012

[4] Neidhardt and Grabrijan: Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity; DZS, 1957, p.6.

[5] Ugljen Ademović, Turkusić, Ibrišimbegović: The Process of Redefining Cultural Identity in Societies in Transition; Case Study: Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, publisher, year, p.2.

[6] Ibid, p.3-4.

[7] Ibid, p.7.

[8] Ibid, p.4.

[9] Ibid, p.7.

We are exploring the architecture of the 20th century in Europe. This weekend we are in Sarajevo on the occasion of Days of Architecture for a talk about the Bosnia and Herzegovina built environment. Sunday, 25th of May at Park Hastahana at 12.00 with Elša Turkušić, Sanja and Igor Grozanić, Amir Vuk Zec, Boro Spasojević, Demir Mensur, Vedad Islambegović; moderated by Boštjan Bugarič (Architectuul) and Elša Turkušić (ICOMOSBIH).

Elša Turkušić (M.Sci. architect) works as a Senior Teaching Assistant at the Architectural Design Department of the Faculty of Architecture, University of Sarajevo. She has been dealing with issues in the fields of architectural design, architectural research and the protection of cultural and historical heritage. She is a Bosnia-Herzegovina’s voting member for ICOMOS International Committee on 20th Century Heritage.

Amir Vuk Zec (1957) is president of the Association of Architects of Sarajevo from 1997. He graduated from the Faculty of Architecture Sarajevo in 1980. His projects include numerous shopping centers, residential and commercial buildings in Sarajevo and renovation of Inat house in Baščaršija. He has also worked in Slovenia and Canada. Since 1997 is leading an architectural studio New Way. He is considered one of the most prominent architects in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Igor Grozdanić (1962) and Sanja Galić-Grozdanić (1962) graduated from the Faculty of Architecture in Sarajevo. They started their careers at the architectural office Dom SPI and Arhiform in Sarajevo. During 1993 they worked in Studio Rondina in Lucca, Italy. From 1993-1998 Igor Grozdanic worked for Henn Architekten, and Sanja Galic worked in the architectural office Ebe + Ebe, both in Munich. After practicing architecture in Italy and Germany, they established their architectural office Studio Non Stop in Sarajevo in 1999.

Demir Mensur (1980) graduated at Faculty of architecture in Sarajevo in 2006. He worked and collaborated at Argentaria, Franz Sacher GmbH Munich, Amir Vuk – Zec. He was a project coordinator for IPA-Project "DELTER” for Eptisa Engineering Services / Spain - improving energy efficiency of public buildings in Bosnia and Hercegovina. He was a guest lecturer and teaching assistant at the Faculty of Architecture Sarajevo. His additional activities include exhibitions, graphic design and documentary films.

Vedad Islambegović (1983) is a founding partner of Filter Architecture (an architectural office based in Sarajevo) and an assistant lecturer at the Faculty of Architecture, University of Sarajevo. Currently working on a PHD thesis related to informal, city-forming processes and their socio-political origin.