Shaping The City Through Participatory Design

I recently had the opportunity of talking with the Slovenian architect and artist Marjetica Potrč about her approach to shaping the urban environment. What does she see as the basic elements and issues? What is the social impact of creating a space. What are the implications for education? Working in different geopolitical contexts, Marjetica develops projects that foster greater participation by local communities and promote local knowledge. Her research is situated at the crossroads of activism, urbanism, and anthropology.

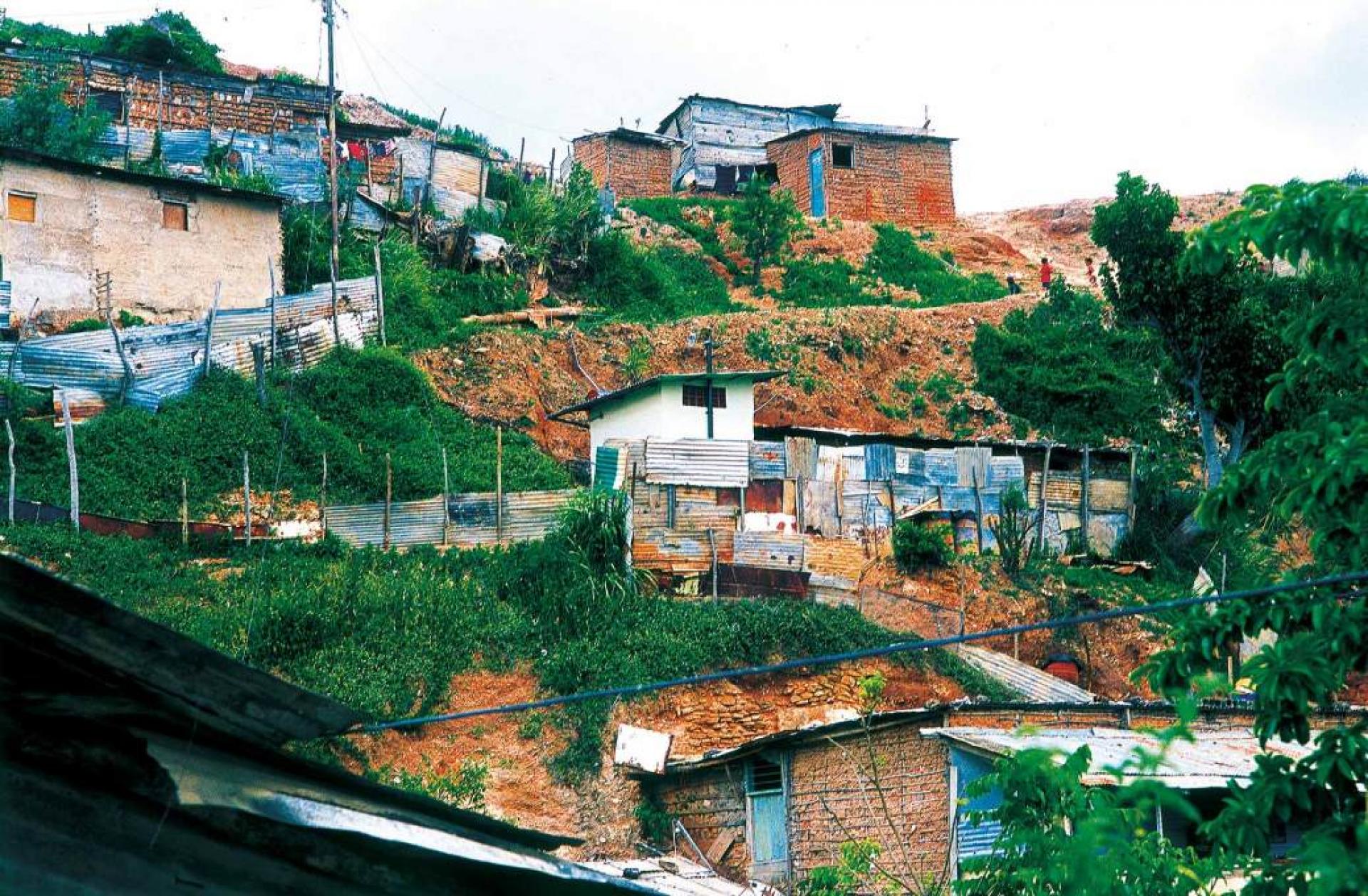

The “Dry Toilet” project (2003) in La Vega barrio, Caracas, was developed by Liyat Esakov and Marjetica Potrč: an ecologically safe toilet was built in a part of Caracas’s informal city that had no access to the water grid. The project was supported by the La Vega community of Caracas, the Caracas Case Project and the Federal Cultural Foundation of Germany, and the Venezuelan Ministry of Environment. | Photo: Andre Cypriano

ELEMENTS

Boštjan Bugaric: Looking at your works, we first encounter strong interdisciplinary approaches in the research and implementation of in situ projects. Your also pointed out that the 21st century challenges of the city lie in its infrastructure. I am wondering how you see the topic of Venice Biennale, which spotlights the fundamentals? What are the fundamentals anyway, and will we need architects, as we know them, in the future?

Marjetica Potrc: Yes, of course, the infrastructure. Think of all the water pipes that need to maintained, or rethought, in our century. Climate change, the awareness of the finitude of natural resources, and the dwindling of state commitments give us an opportunity to rethink those water pipes, since the water supply will change anyway. The main question is: how we will use water? It’s about people. When my team worked on the Dry Toilet project in the Caracas informal city in 2003, we realized that it is more difficult to change human behavior than to construct a building. That was 10 years ago. I see the Dry Toilet project as a good exercise when we think of the upcoming challenges facing urban populations. The dry toilet in the La Vega barrio in Caracas does not need any water to operate; it was constructed with the residents of La Vega barrio on a site where there was no water infrastructure available, so we are talking about an extreme situation. It’s not that there will be no water in the world’s cities of tomorrow - although for Delhi and Beijing, water shortages are already a big problem. The main question is: What is the social contract? Architecture comes afterwards. Can I say that the social architecture is what is most important at this time?

The project “La Semeuse” at Les Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers in the Paris suburbs (2011-ongoing) is a vegetable garden and platform for ecological urban gardening. It was developed by Marjetica Potrč, RozO Architectes (Severine Roussel and Philippe Zourgane) and Guilain Roussel. | Photo © Les Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers

You ask about the Venice Architecture Biennale - I am not a regular visitor to the exhibition. I missed the one this past year. I loved the exhibition “Architecture Beyond Building” curated by Emiliano Gandolfi at the Italian Pavilion in 2011. It was an energetic, imaginative exhibition that showed ideas that many young architects are exploring. Not only were socially oriented projects exhibited, but also works and ideas that demonstrate the redefined role of architects beyond concerns driven by neoliberal economics. The exhibition attempted to go beyond the status quo of an architecture of convenience. Emiliano Gandolfi wrote 'A Possible Manifesto' for the occasion, and it still stands for me.

I stand by socially engaged design. Work made in this direction serves people. I like to think of socially engaged projects as laboratories, as tools for reimagining our life in cities. Cities need small-scale socially engaged projects for the simple reason that the state, and the social state in particular, is withdrawing its support. The questions arise: what is the balance between the top-down organization of cities and bottom-up initiatives? Is the current social contract satisfactory and, if not, in what way will it change? In what way will the laws that lawmakers carefully constructed during the last century be redefined? It has been a long process, but now we know that articulated local communities are welcome to the discussion table. This is important.

In the EU, one of the biggest shifts experienced today is the dissolution of social state and its transformation into a participatory society. “The welfare state of the 20th century is over. The classical welfare state is slowly but surely evolving into a participatory society.” This is what the new Dutch king said in his inaugural address a year ago. From my point of view, I see local communities’ participation in governance as a crucial building block in the construction of society from below, which I see as necessary. Sustainability is local, right? But I find it super interesting that left and right politicians, activists and top-down managers, are talking the same language: it’s about participation! Is participatory budgeting a dirty word, an inspiration, or simply a reality to deal with? I like to tell the story about left- and right-of-center politicians saying basically the same thing. When they came to power, the current right-of-center British government talked about “a ground-breaking shift in power to councils and communities” - a phrase you might sooner expect to hear from Hugo Chavez, the late leftist president of Venezuela. Beyond making strange bedfellows, such enthusiasm for the local pushes us to redefine the meaning of such terms as “social innovation” and “sustainability,” which have been clouded by neoliberal discourse and hijacked by neoliberal practices that try to accommodate the vanishing middle class.

The King’s Cross Pond Club was a public art project, commissioned by King’s Cross Central Partnership as part of the Relay Art Program. OOZE and Marjetica Potrč occupied a temporary site in the midst of the King’s Cross construction site in London and created a micro-ecological environment with a natural swimming pond at its centre. | Photo © John Sturrock

CONTENT

BB: Speaking about architecture that carries social engagement, we could find a different approach of scale. Projects are executed in a smaller scale with bottom-up participation and research into participatory methodologies for social engagement. You talked about four principles of cooperation, can you explain what did you mean by these principles?

MP: Take the Curry Stone Design Prize. This is a platform that makes visible work by designers, architects, activists, etc, who address critical social needs. They believe that design can be a force for improving lives and strengthening communities across the world. The stories of change gathered on the website are powerful statements.

Between the Waters: The Emscher Community Garden' is a water-supply infrastructure line between the Emscher River and the Rhine-Herne Canal. The project is a complete and sustainable water-supply system. It uses only water from the immediate area: the Emscher River, the Rhine-Herne Canal, rainwater and waste water. | Photo © Roman Mensing

Socially engaged design is a borderline discipline that lies between design and sociology, design and environmental science, design and activism, etc. I see it as a crucial discipline because it tests new practices; it tests how we want to live together. It’s never enough to talk. You need to make things together to be able to think differently. You need to perform a ritual of transition; you need to cross a bridge. There is so much work to do, and to do it well you have to explore new possibilities by everyone really. Socially engaged projects are essential because they focus on people. There are many initiatives around the world in this direction, and some of them are highly visible: Architecture for Humanity comes to mind. The societies of the world are, after all, an organism, and they have the power to reimagine the world through new practices when old ways do not work any more.

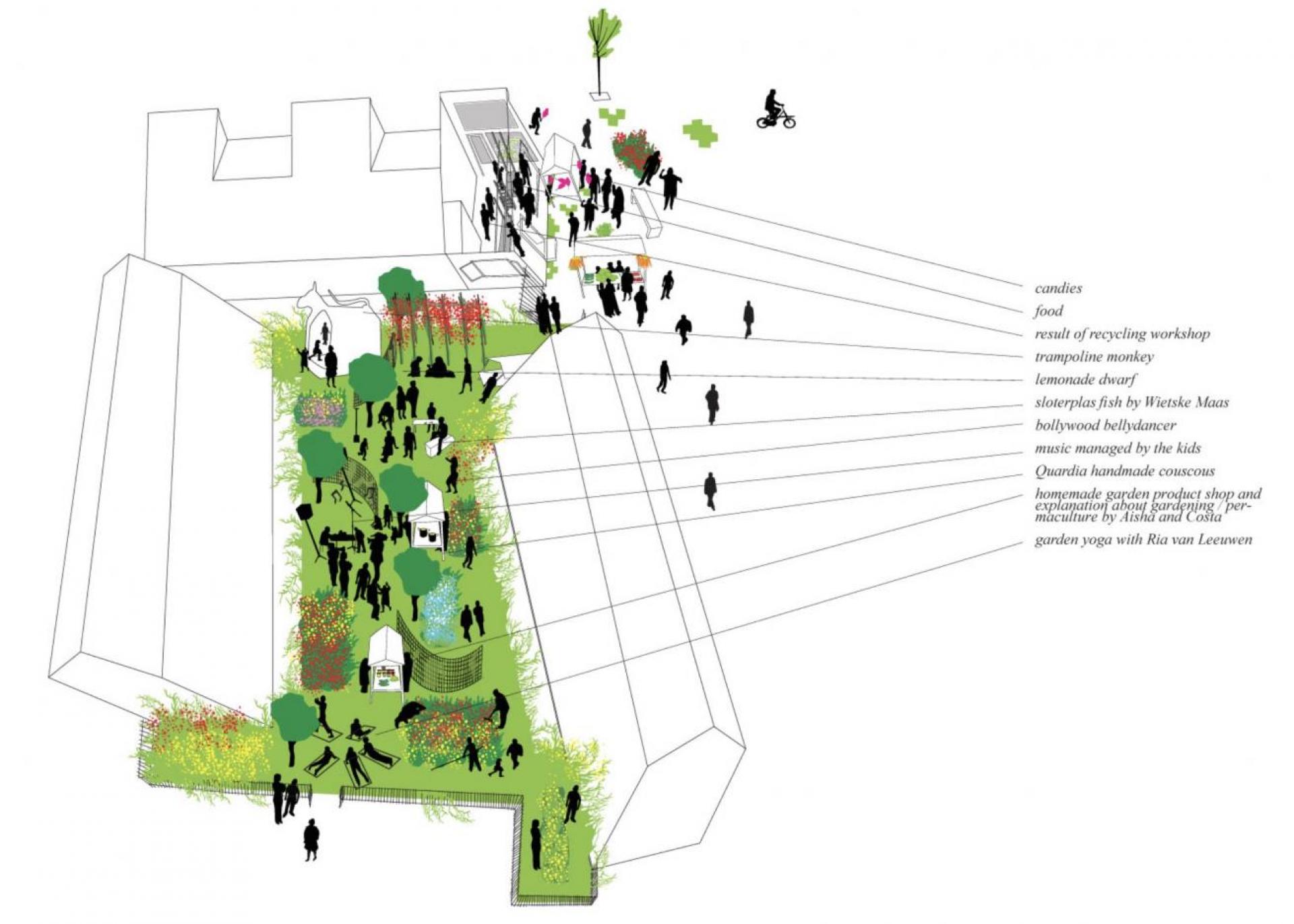

A successful, and somewhat unexpected, argument for the cause comes from community gardens - the strong increase in community gardens in European cities. They are organized and maintained by residents. They are not organized the municipality - although some government agencies are carefully following this development and others are trying to learn from it. What we see at the center of this effort for community gardens is participatory design. It would be interesting to find out what the failures, the limits, of community projects are now that the practice has established itself. The Prinzessinnengarten in Berlin comes to mind.

We tend to forget that participatory design is not a new discipline. It is an old discipline. It was pushed under the rug for a while but it is again in focus. The projects we develop in my participatory practices class at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg - the class is called Design for the Living World - follow four principles of participatory design. They are quite simple: listening to and talking with residents before making a definite plan; involving the community in the decision-making and design processes; involving the community in the construction process and transferring the responsibility for the developed project to the community in order to leave behind a sustainable work that benefits the community in the long term.

The four steps have only rarely been put into practice because political decision making is fast but community building is a slow process. Such projects have the potential to change public policy. Jeanne Van Heeswijk and her collaborators did just that with their involvement in the Market of Tomorrow project of 2008, which was an effort to revitalize Rotterdam’s Afrikaandermark. The challenge is how to connect participatory projects on a larger, legislative scale. Cities need this practice.

SOCIAL

BB: In your recent works you enter the field of community gardens and the urban commons in order to apply Lefebvre’s idea of the Right to urban topics. You worked on the Soweto Project in South Africa with your students from the Design for the Living World class for two and a half months. You have said that the project is about place-making and that place-making is a slow process. Only in such a way can residents have a better understanding of the project. But sometimes this also leads to failure. How do you respond when failure occurs in the work process, when the residents are not ready to participate?

MP: There are no residents who do not want to participate. But there are many flawed participatory strategies that turn residents away. In the projects we do in our class, we don’t just drop something on a community. We work in collaboration with the residents to develop a project that benefits the community. From the beginning we say: “This is not our project. This is your project.” The thing that is most important for the success of a project is to empower the residents to take over the project themselves. Residents who take over the project do not need us anymore - this is a successful project.

The diagram of the community garden and community kitchen in Amsterdam. | Diagram © OOZE

The Soweto Project I worked on with my students and Soweto residents earlier this year is a good example. The Soweto Project developed over the course of two months in early 2014 in two Soweto neighborhoods - Orlando East and Noordgesig. In Orlando East, the Design for the Living World class and the local residents turned a former public space that had been used as a dumping ground into a community-organized public space called Ubuntu Park. Together, we built a stage, braai-stands (barbecue stands), tables and benches. To open Ubuntu Park, and to celebrate the community, we organized the Soweto Street Festival. In Noordgesig, we helped develop two vegetable gardens at Noordgesig Primary School. In all these endeavors, we followed the principles of participatory design.

“The Noordgesig Primary School Vegetable Gardens” (2014) was part of the Soweto Project by Marjetica Potrč and Design for the Living World, her class at HFBK Hamburg. The project was made at the invitation of Nine Urban Biotopes – Negotiating the Future of Urban Living, a project by urban dialogs Berlin, and supported by the Culture Program of the European Union and HFBK Hamburg. | Photo © Maria Christou

Ubuntu Park is community-organized public space in a Soweto neighborhood. The residents have formed two representative bodies, the Ubuntu Park Committee and Environ Ubuntu Park Projects. They have taken on practical responsibilities. They are planning future engagements and new partnerships. By engaging and empowering the community, the project became an initiative for sustainable living. It addresses such issues as security (the park is free of crime and drugs, so children can play here and residents can socialize); maintenance of the area by the residents themselves; food security - getting local residents involved in vegetable gardening; and the creation of an arts and culture program for the park stage. Also, as a collaboration with the city’s social development department, the park can serve as a prototype for the kind of neighborhood development that’s not a “hands out” but a “hands up” approach. The social development department and the mayor’s office want to change the culture in government agencies that are sclerotic and corrupt. They see Ubuntu Park as a prototype that demonstrates in practice how the city grows from its neighborhoods. In that sense, Ubuntu Park is a relational object that residents use to transform their city.

Two months after we left Soweto we received a letter from Themba Skosana, an Ubuntu Park Committee member, who told us that a new representative body called Environ Ubuntu Park Projects had been formed. Unlike the Ubuntu Park Committee, which looks after the maintenance and organization of the park, Environ Ubuntu Park Projects seeks to build new partnerships with the broader Soweto and Johannesburg communities and beyond. The new partnerships will help the community raise money and negotiate their interests with government institutions.

Ubuntu Park is part of a social agreement the community has made among themselves. If for some reason the agreement collapses, the park will probably become a no man’s land again. Before it became Ubuntu Park, the site had been a dumping ground for more than 40 years. But so far, no dumping has occurred in the new park. The social agreement is still holding.

“Soweto: Ubuntu Park” (2014) was also part of the Soweto Project by Marjetica Potrč and the students of Design for the Living World. | Photo © Radoš Vujaklija

EDUCATION

BB: We started our conversation with the topic of architecture without an architect. Education about space in general should be a right for everybody, especially because in the future we will be faced with many new situations like climate refugees, migration camps, urban food production, and others, which will require informal education to understand how it is possible to work in the field of place-making. You said that you teach students how to learn with/from people. Could you explain this position a bit more?

MP: Well, I like to say that a university is a learning and teaching platform; it is an association of students and teachers, in the classical understanding of the university. It is a laboratory for developing new practices, beyond being an academic institution that dwells on already established knowledge. For me, the focus on social architecture and open-source architecture makes sense; it answers the call of our time.

“Soweto: Ubuntu Park” (2014) – The Soweto Street Festival. | Photo © Terry Kurgan

As we know, ninety-four percent of the architecture around the world is not built by architects. So it makes sense to reimagine the school. My students talk about their role as mediators and collaborators. We believe that participatory projects, which gather and use knowledge across disciplines, can be catalysts of change. Together, we create tools that communities use to make a better place for them to live. Along the way we have developed a vocabulary to explain the practice, with such terms as “relational objects” and “performative actions.” With Ubuntu Park, for example, the stage we constructed with residents was a relational object. The Soweto Street Festival was an example of performative action. Let me explain.

The construction of the platform stage and the cultural programming connected with it represent an example of place-making - a process through which a group gains recognition in society by creating a physical space for themselves. That’s why the platform captured the imagination of the residents and, in a way, expresses the whole idea of Ubuntu Park. The platform was first used at the Soweto Street Festival, and there have been other cultural programs since; for example, we heard that the stage is used regularly for dance practice, singing, and poetry readings with schoolchildren as after-school activities. The stage has become a symbol for a new appreciation of the local culture and an affirmation of the community’s identity.

The platform was built with a minimal budget, which proved to be an exercise in giving value to human resources. It was built with no permit, on a no-man’s land that existed beyond the enforcement of municipal regulations. In this vacuum, the non-space became a site of possibilities, where the community could imagine a new kind of public space: a community-organized public space.

The Soweto Street Festival was a performative action made by and for the people who live in Soweto. The strength of a performative action is its role as a mirror. When residents took part in the festival, they saw an image of themselves that was one of openness, curiosity, happiness, playfulness, and strength. The mirror said: “This is who we are.” It was the embodiment of a possibility, of a positive transition from the status quo and decades of inaction, when the site was just a dumping ground.