The Women Housing Architects Of Britain

Although women contributed in many ways to British architecture before the twentieth century, they officially entered the architectural profession only after the First World War. The RIBA did not admit women until 1898, when Ethel Charles (1871-1962) became a member, opening the debate on women’s role in architecture and causing a legalistic and bureaucratic resistance.

Elisabeth Scott’s competition design for the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon (1927) marked the beginning of a breakthrough for women architects. | Photo via Architecture.com - RIBA Collections

Since then, British women architects have fought to redefine their professional identity, gaining access to education and big projects and often demonstrating to be architecturally and socially innovative. Among them, a few remarkable figures worked for local authorities in London and contributed to the public good with bold, progressive and human buildings and their multidisciplinary skills. Mainly involved in housing projects and often collaborating with each other, Elisabeth Denby, Judith Ledeboer, Rosemary Stjernstedt, Kate Macintosh and Alison Smithson can be considered inspiring and unsung pioneers who played a crucial role in social architecture and in the formulation of housing policy.

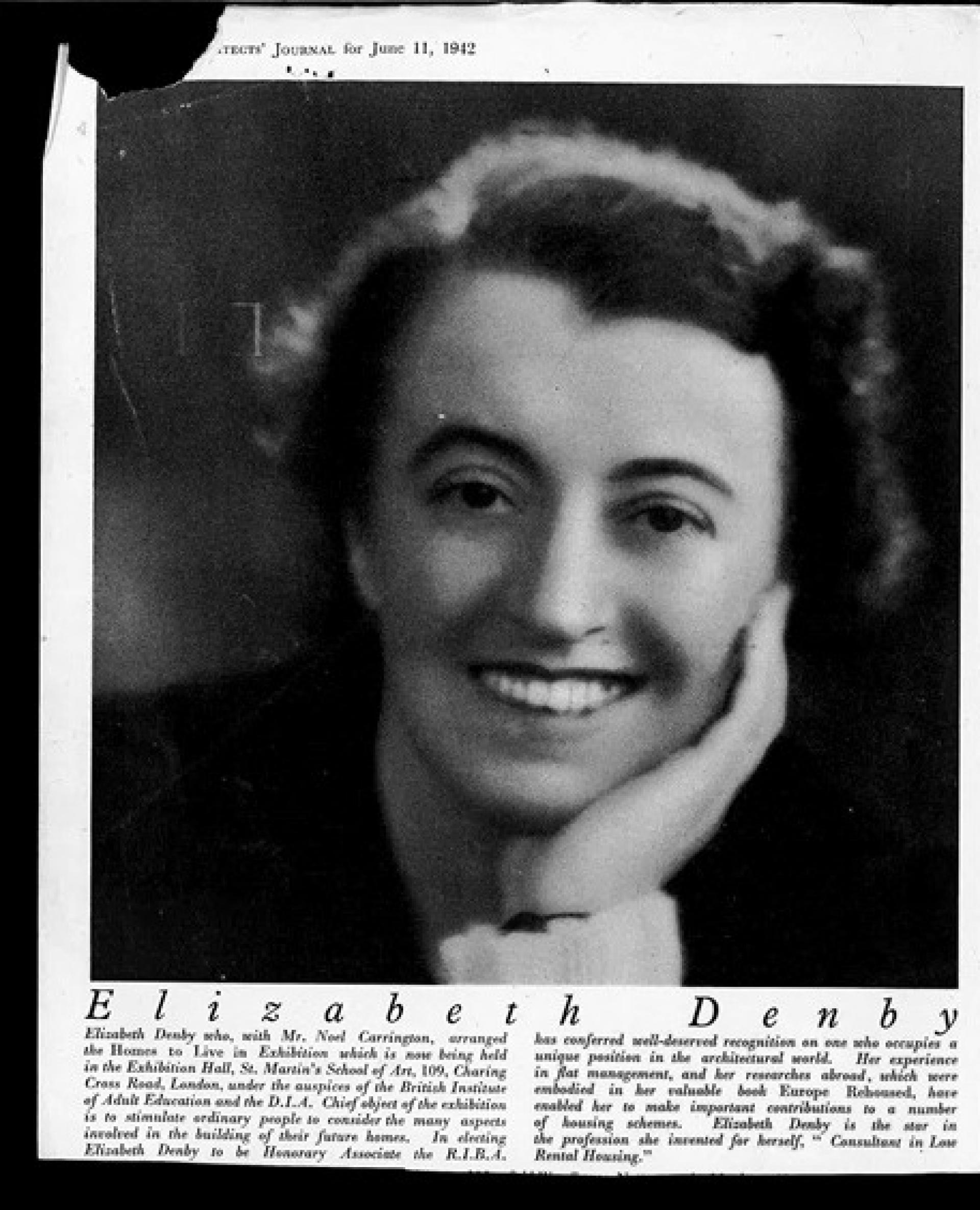

Elizabeth Denby, the England’s Jane Jacobs, was an urban planner, housing consultant and social reformer. | Photo via Architects’ Journal

Elisabeth Denby soon became a champion of urban renewal and a fundamental figure for the development of British housing program. Collaborating with Maxwell Fry who defined her as the leading spirit in housing in the 1930s, she designed several inner city flats where she applied her innovative ideas to respond to residents’ needs. Their Sassoon House has been defined the first modernist workers’ dwellings in Britain.

Denby contributed to the discussion about residential planning with the book Europe Rehoused.

Fry and Denby used Kensal House to put into practice Modernist ideas for social change starting at home, offering carefully-planned flats with generous kitchens, bikes storages, gardens, large balconies and nursery. | Photo by Edith Tudor Hart at RIBA Collections

Elizabeth Denby was on the RIBA Housing Group with Jane Drew, Judith Ledeboer and Jessica Albery. The result of their collaboration was a report published in 1944 where they expressed their views about the future of housing, inviting decision-makers and colleagues to opt for carefully-designed terraced houses and flats instead of inhuman high-density complexes.

Born Dutch-English, Judith Ledeboer was an architect who collaborated with David Booth and John Pickheard. She became another significant voice in housing policy. Astragal, the diarist in the Architects’ Journal wrote in 1934: “In our little world Miss Denby and Miss Ledeboer wield more influence and get more work done than any six pompous and prating males”. In 1941 was the first woman employed by the Ministry of Health responsible for housing. Ledeboer also advised local authorities on the reconstruction of post-war Britain and contributed to the establishment of those space standards that then became mandatory in all public housing.

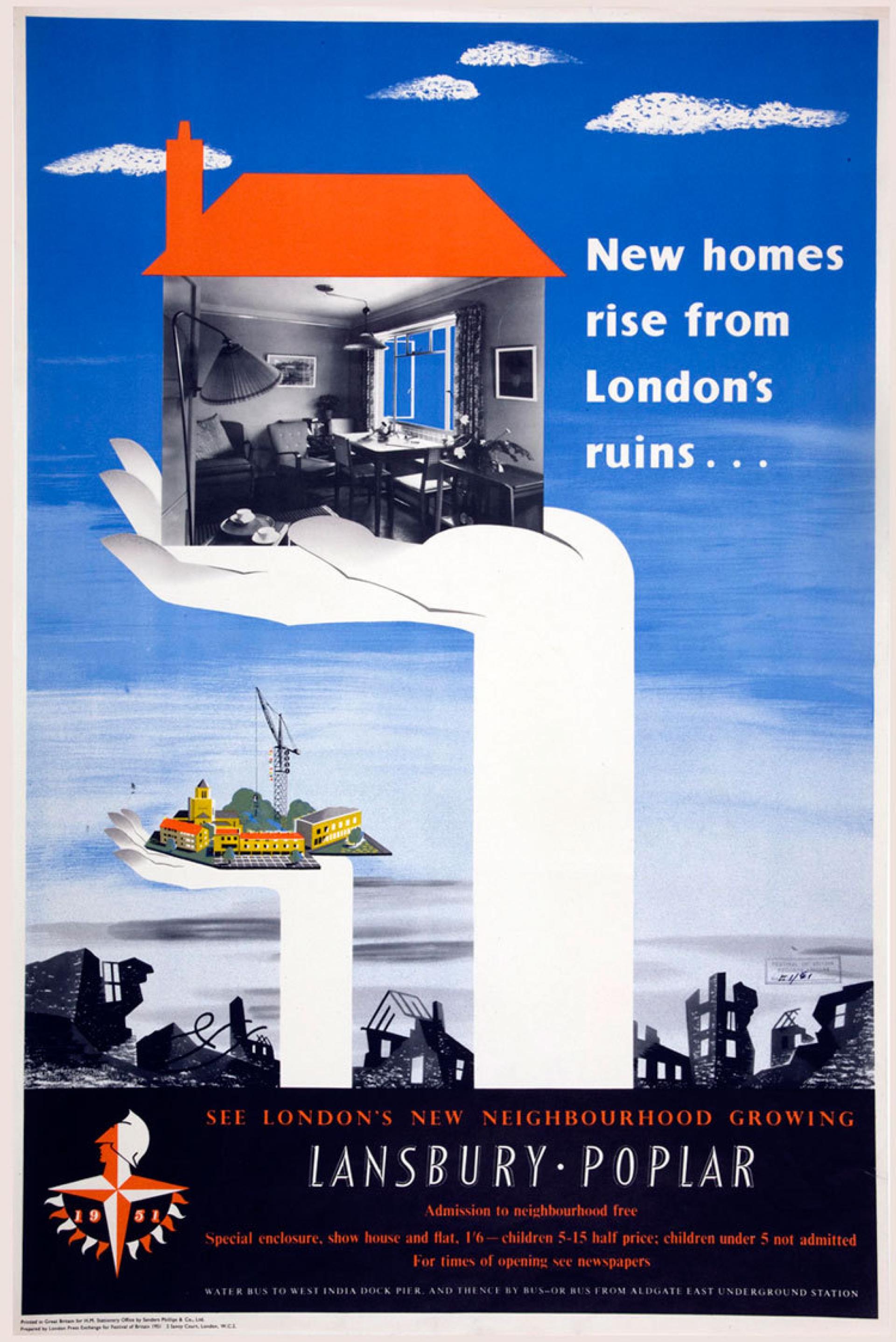

Poster for a new housing estate in Poplar, which is being advertised as a paid attraction during the 1951 Festival of Britain. | Photo by Festival of Britain

Also other women architects worked for the public sector and took crucial roles in Britain’s era of social housing provision with major schemes in the 1960-70s. AA-trained, Rosemary Stjernstedt moved to Sweden to work as town planner and returned to England after Second World War, joining the London County Council in the Housing Division. There, she was the first female architect to achieve Grade I status and she became the first woman to reach senior grade I status in any British council county division in 1950.

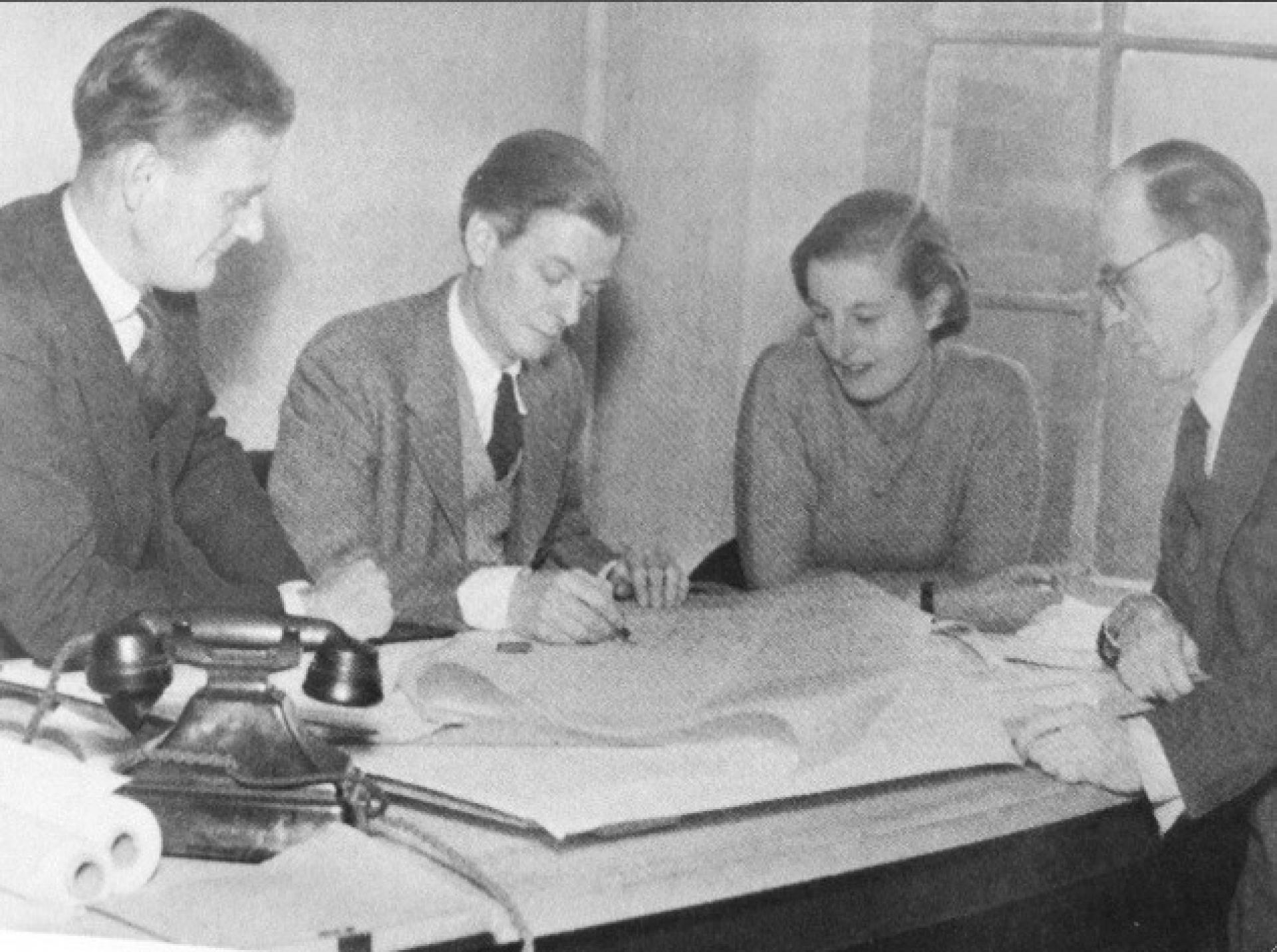

Rosemary Stjernstedt with her fellow architects in the LCC Housing Division (1950). | Image via Guardian

Her best-known project was the Alton Estate, which she designed in the role of the team leader in 1951-55, described by Pevsner as architecture at ease. When London County Council was dissolved in 1964, Stjernstedt started working for Lambeth Borough Council under the guidance of Ted Hollamby, a committed socialist architect and planner.

Alton Estate has over 13,000 residents with the brutalist architecture inspired by Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation. | Photo via The Modern House

Under Hollamby, Lambeth’s architects produced several housing and welfare buildings, making the borough now nationally known for the ambition and quality of its output. In 1968, Kate Macintosh also joined Lambeth’s Architects’ Department where she embarked on 269 Leigham Court Road, a sheltered housing for the elderly. Responsible for some of the most innovative housing schemes commissioned by several local authorities, Macintosh believed that one of the generators of our work was the search for social justice. She was only 26 when she began designing Dawson’s Heights.

Leigham Court Road Robin London. | Photo © Kate Macintosh Archive

Among architects who contributed to London’s social housing, Alison Smithson, born Alison Gills, gave life with Peter Smithson to the New Brutalism and its interest in accommodating and adapting to the real experiences and desires of ordinary people. She worked in the architecture department of the London County Council before starting a practice with her husband in 1950.

Alison Smithson at Hunstanton Secondary Modern School, Norfolk, during its construction. | Photo © Nigel Henderson Estate

If Rosemary Stjernstedt’s Alton Estate was clearly inspired by Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation in Marseille, Alison and Peter Smithson brought to light new theories in antagonism to the Swiss-French master’s principles. As the only woman in Team X, a radical group formed to replace the CIAM philosophies of high modernism, Alison stressed the importance of the real social architecture needs and housing design solutions becoming internationally influential with numerous theoretical writings. Recently, the western block of their famous Robin Hood Gardens complex has been demolished opening a large debate so that now part of the building has been preserved by the Victoria and Albert Museum and was presented at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2018.

In the Robin Hood Gardens the street-in-the-sky concept took form as broad aerial walkways into the long concrete blocks. | Photo © Lorenzo Zandri 2018

These five women are a most representative example of the extraordinary female contribution to social architecture in the United Kingdom in the post-war period when, despite the high pressure of housing needs, they proposed high quality projects designed for people. At a moment when the number of social homes being built in England is at its lowes and local authorities struggle in providing quality housing, we can learn from their experiences, projects and theories, recognising them as best practices and monitors for the current and future challenges.

Pioneer Architects XV by Giorgia Scognamiglio and Lorenzo Zandri