Sitopia: Shaping Our Future Through Food

To eat and to dwell are two fundamental human needs, satisfied respectively by food and architecture. Despite their importance for human lives and the mutual deep connection, we still rarely see the two phenomena discussed and considered together. The FoodCAMP series at Prague’s CAMP - Center for Architecture and Metropolitan Planning was searching for answers to the question How can food make our cities better?

Building sitopia: MVRDV’s masterplan for Almere Oosterwald. | Photo ©MVRDV

The curator of the event Lucie Kohoutová explained that she “wanted to tackle the intricate synergies of culinary and urban worlds from different vantage points, from city identity through urban farming to quality architecture of food-related venues.” Lucie said that was also very important to pick an adequate keynote, framing how and why food matters to our city lives. She chose Carolyn Steel, an architect and leading thinker on the relationship of food and the city, also known by her book Hungry City. Carolyn has summed up her Prague’s lecture only for Architectuul below.

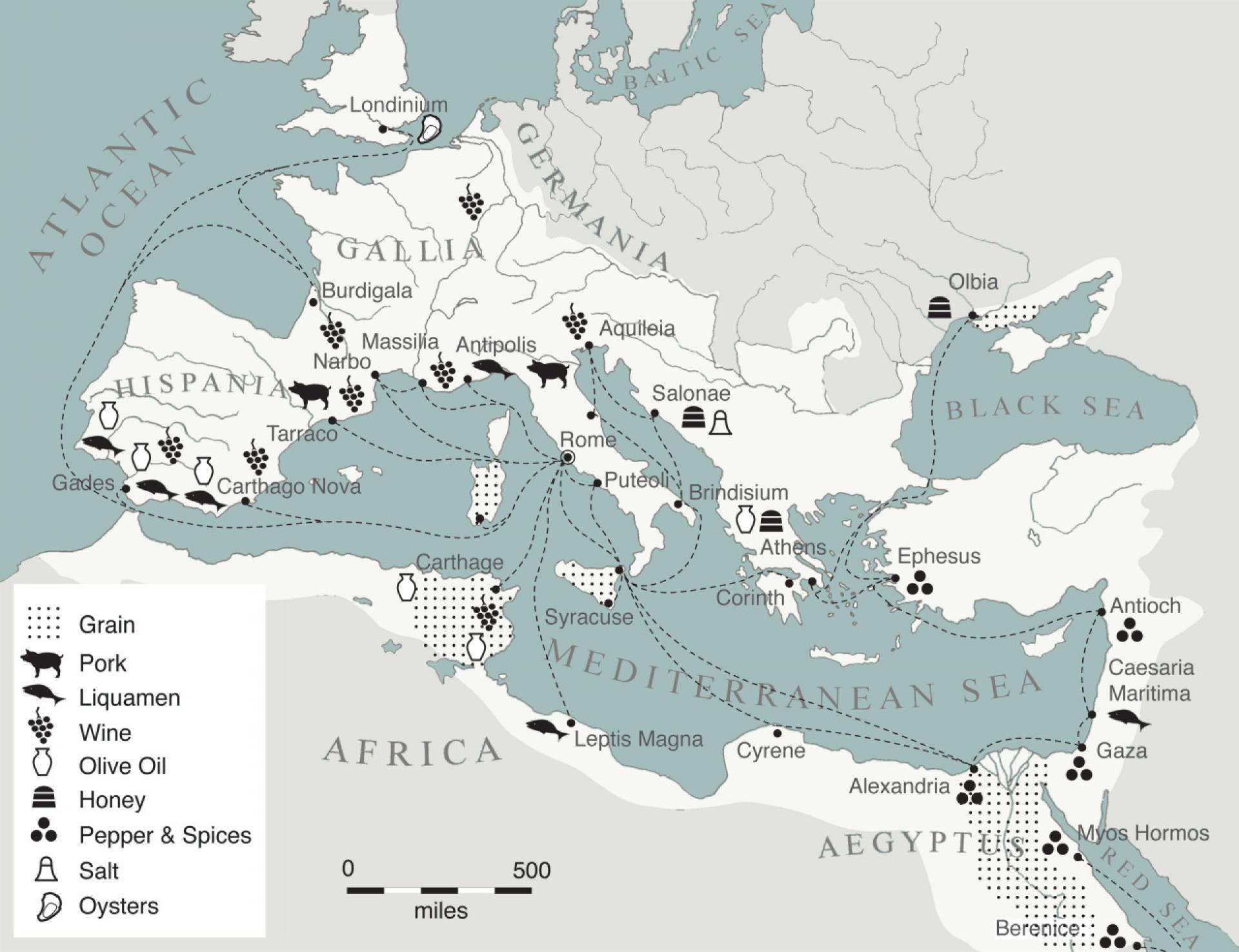

Roman Food Miles: the food supplies of Ancient Rome. | Photo © Carolyn Steel

How will we eat in the future? Will meat be grown in labs and vegetables in vertical farms, or will we see a resurgence of regenerative, organic farming? Whatever the answers, one thing is clear: our choices will be pivotal to our chances of thriving on a hot, overcrowded planet.

Living in a modern city, it can be hard to grasp quite how profoundly food shapes our world. Industrialisation has obscured the vital connections between city and country that are fundamental to urban civilisation. Yet the food on our plates is more than mere nourishment: it is an emissary from distant lands that have often been plundered to the point of exhaustion to provide us with that essential foundation of modern industrial society, cheap food.

A city shaped by food: seventeenth-century London’s food markets and supply routes. | Photo © John Ogilby: A Large and Accurate Map of the City of London (1676); London and Middlesex Archaeological Society (1894)

Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Allegory of the Effects of Good Government: a rare example of the city and the country in harmony (1338). | Photo via Palazzo Pubblico, Siena. (Bridgeman Art Library)

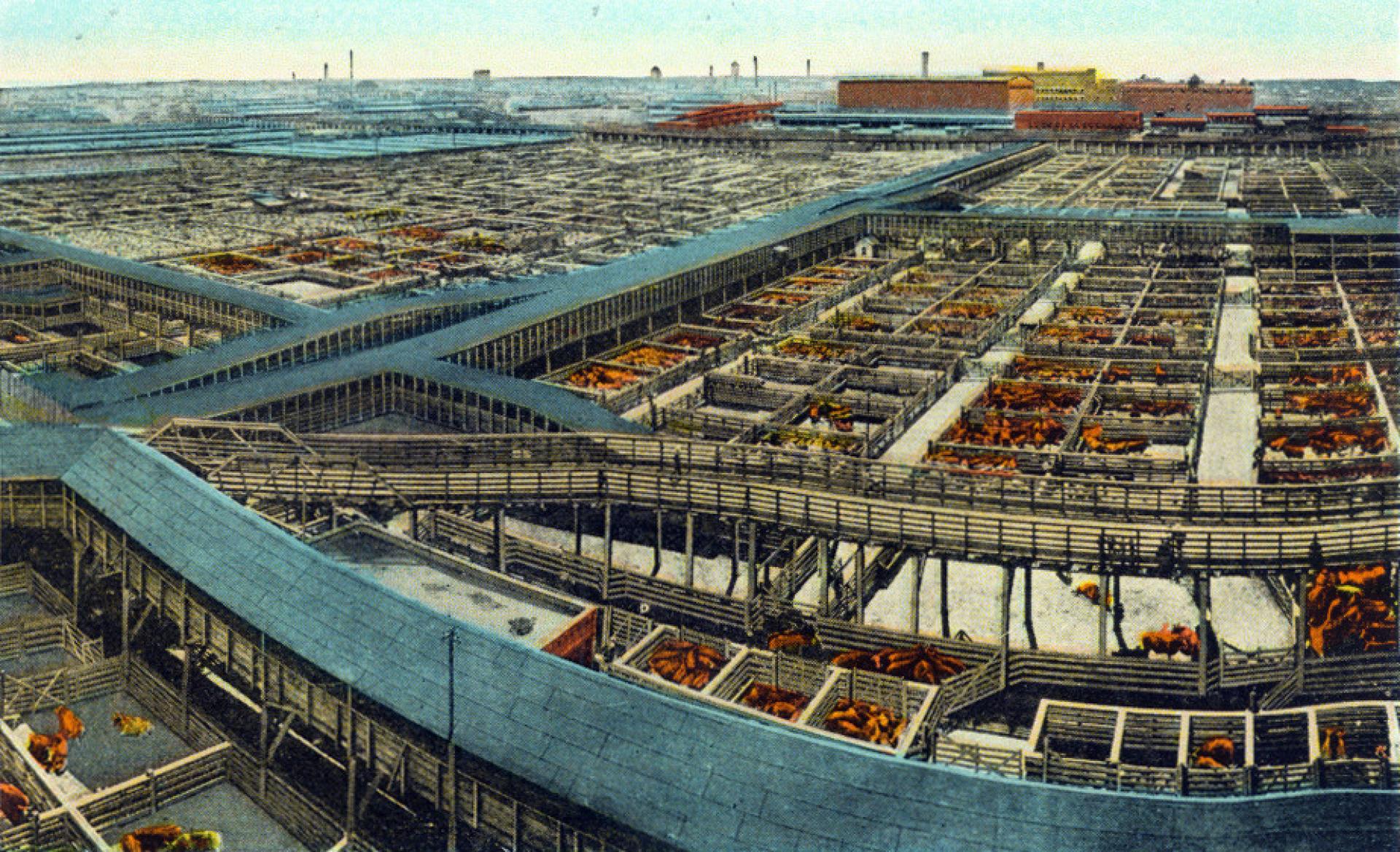

Our way of life is predicated on the stuff, yet a moment’s reflection should tell us that no such thing could exist. Food consists of living things that we kill in order to live; to expect it to be cheap is thus to cheapen life itself. This paradox lies at the heart of our modern dilemma: our way of life is based on the assumption (posited by Adam Smith and others) that although nature is the source of all our wealth, it comes for free – one that we now know to be false. Indeed, the various externalities of cheap food – climate change, deforestation, mass extinction, pollution, water scarcity, soil degradation, obesity and diet-related disease – suggest that, were we to internalize such costs, industrial food would become instantly unaffordable. Which begs the question: what would happen if we were to do precisely that?

The short answer is that there would be a revolution, not just in the way we eat, but in how we live. Our habits, values, politics and economics – indeed, our very idea of a good life – all depend on the fallacy that we’ve solved the problem of how to eat. Any attempt to revalue food will thus be met with stiff resistance, not least among politicians. Yet such a move is arguably the single most powerful thing we could do in order to transition from our inequitable, unhealthy, unsustainable societies towards far fairer, healthier, more resilient ones. Whether or not we realise it, we live in a world shaped by food: a place I call Sitopia (from Greek sitos, food + topos, place). By revaluing food and harnessing its power for good, we can create a better world.

The birth of cheap meat: Chicago’s Union Stockyards in 1880. | Photo © Postcard, unknown origin

Food’s power wasn’t lost on our ancestors; on the contrary, it dominated their lives. Feeding cities in the pre-industrial era was hard, not least due to the difficulties of transporting food over long distances to arrive in an edible state. Although grain (the staple of all cities) had a reasonable shelf-life, it was heavy and bulky in relation to value. For this reason, most cities remained small. The exceptions were maritime capitals such as Rome and London, whose ability to import food from overseas allowed them to grow to an inordinate size. Whatever their scale, all pre-industrial cities were highly productive: households kept pigs, chickens or goats and human and animal manure was used to fertilise surrounding market gardens, orchards and vineyards.

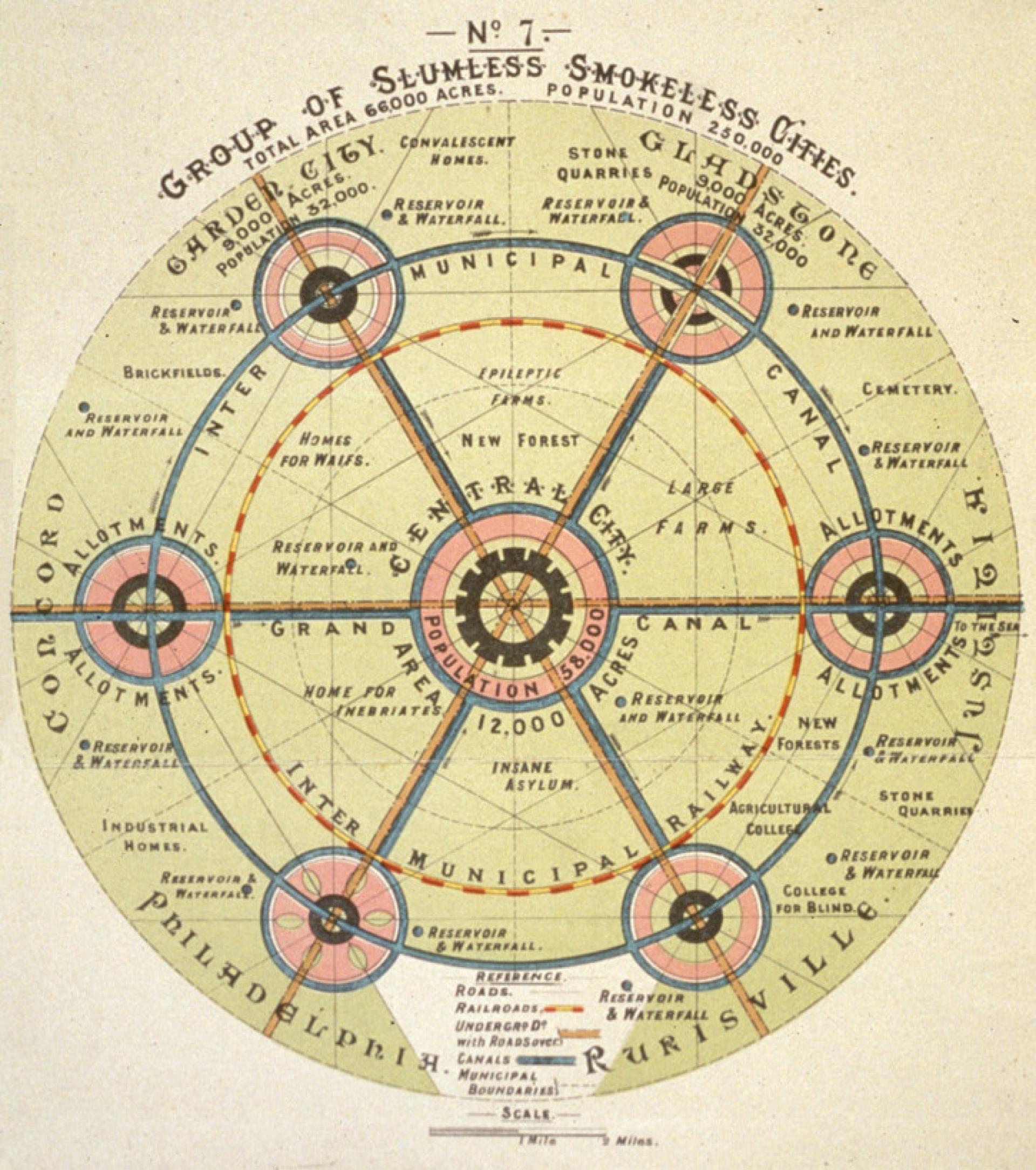

For Plato and Aristotle, such self-sufficiency was the ideal for the polis (city-state). Both men preached the principles of oikonomia (household management): the idea that each urban citizen should feed his family from his own farm. Scaled up, such an arrangement would render the polis self-reliant and politically independent. The ideal polis should thus remain relatively small; an idea echoed by both Thomas More in his Utopia of 1516 and by Ebenezer Howard in his 1902 Garden Cities of To-Morrow.

Reviving oikonomia in Howard’s Garden City. | Photo via Ebenezer Howard, Garden Cities of Tomorrow, Sonnenschein Publishing (1902)

Conceived at a time when the need to conserve resources and recycle nutrients was obvious, such utopian models are once again highly relevant, describing the more localised, steady-state economies we shall need in order to thrive in coming decades. By revaluing food – putting the oikonomia back into economics – we can build more liveable, resilient societies based, not on consumption, but the joys of community, productivity and contact with the natural world. Domestic life would once again revolve around kitchens, gardens and shared meals, markets and highstreets would flourish, gardens and balconies burst with produce and networks of producers and suppliers reconnect cities with their hinterlands. Instead of battling nature, farmers could work with it, replacing industrial feedlots and ‘Big Ag’ monocultures with a variety of mixed-use, agro-ecological farms and rewilded land.

The future of food? Richard Ballard, co-founder of Growing Underground, London’s first vertical farm. | Photo © Carolyn Steel (2018)

Such a vision may sound utopian, yet across the world it is already happening. As millions in the global Food Movement recognise, the era of cheap food is over. The good news is that it is not too late: by putting food back at the heart of our vision, we can build a flourishing sitopian future.

—

Written by Carolyn Steel

Carolyn Steel (MA (Hons) Cantab Dip Arch RIBA) is a leading thinker on food and cities. Her 2008 book Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives describes how food is key to the ‘urban paradox’ at the core of civilization, and her concept of sitopia (foodplace) has gained widespread recognition as a tool with which to address the dilemmas of 21st century dwelling. A Director of Kilburn Nightingale Architects in London, Carolyn has been a visiting lecturer at Cambridge and Wageningen Universities and taught design for a number of years at Cambridge and London Metropolitan Universities and the London School of Economics. She writes regularly on food, architecture and urban design, has presented on BBC TV and was a columnist for Building Design. She is in worldwide demand as a public speaker, with appearances including TEDGlobal, The World Planning Day International Conference, The Netherlands Environment Assessment Agency, The Swiss Youth Forum, Princeton University (New York), The Parabere Forum, MAD Academy (Copenhagen), Domus Academy (Milan) and the Melbourne Design Festival.