Pioneer Architects XII

Pioneer Architects is at the hundred anniversary of the Bauhaus dedicated to all women architects and educators who became role models with their pioneer work influenced by the movement.

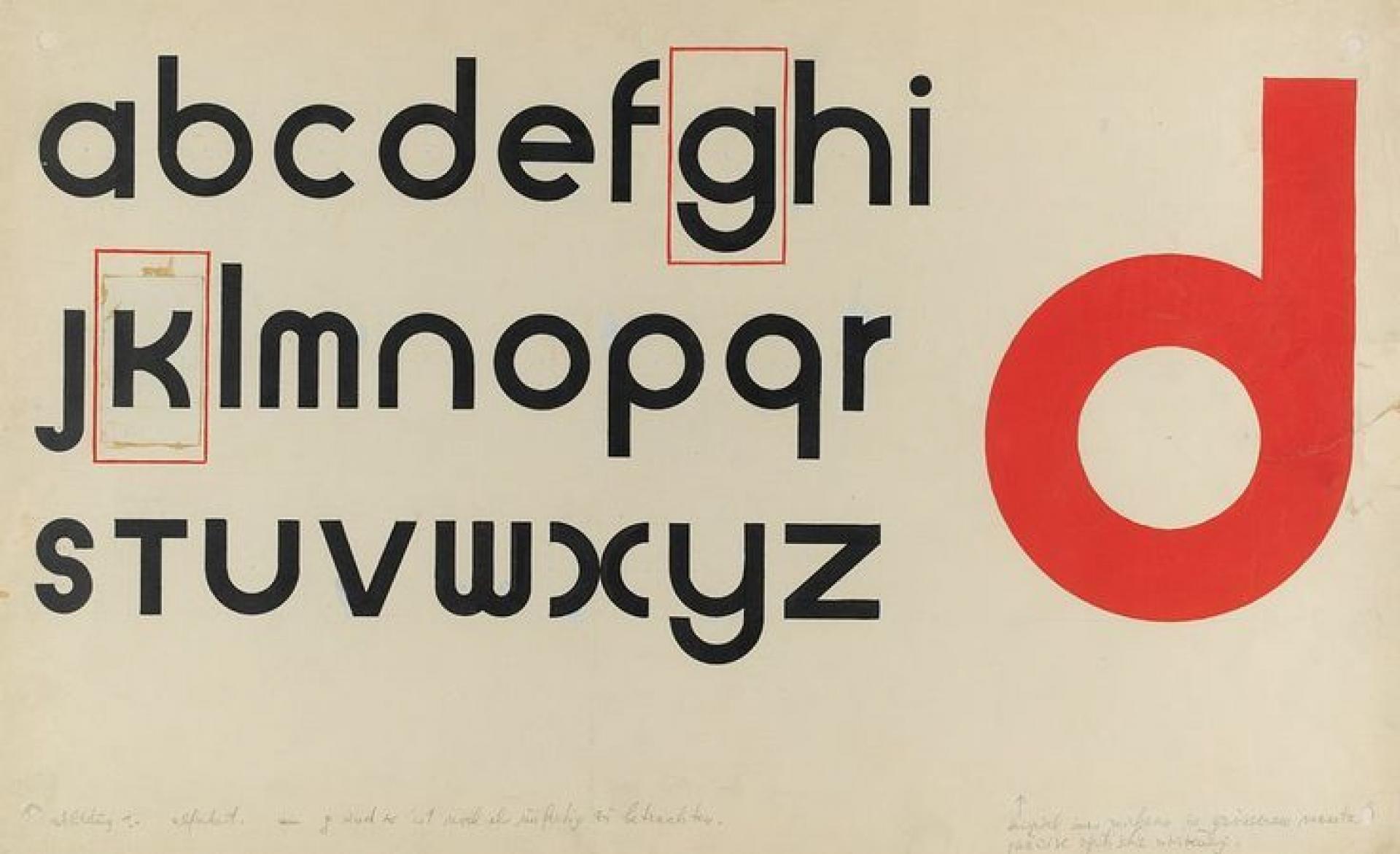

Research in development of universal type by Herbert Bayer (1927). | Photo via Harvard Art Museums; Busch-Reisinger Museum

According to Walter Gropius Bauhaus school need to be open to “any person of good repute, regardless of age or sex.” In this time women couldn’t receive a public education in many fields, so he meant this with good intentions.

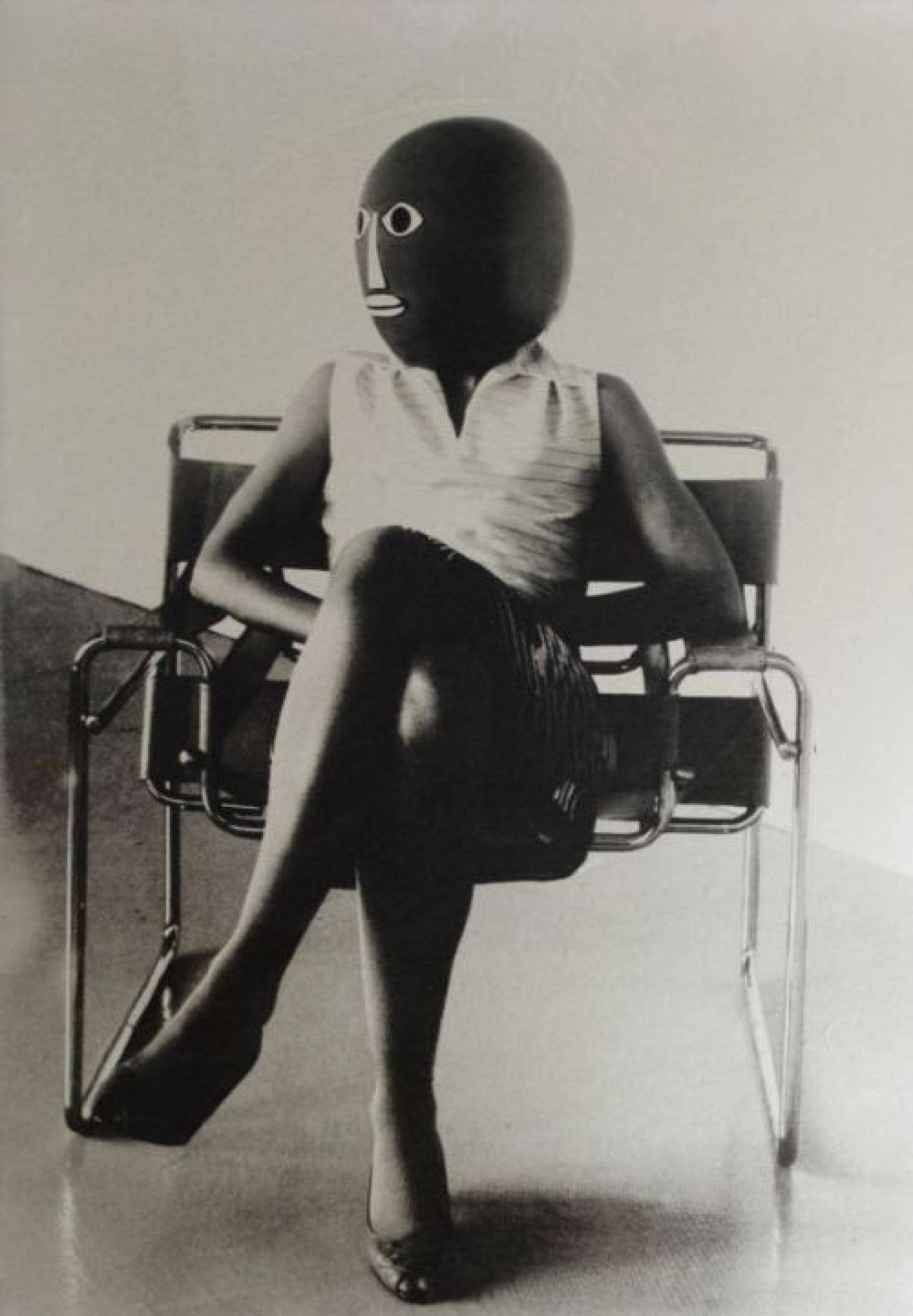

Unknown student in Marcel Breuer Chair. | Photo by Ursula Mayer

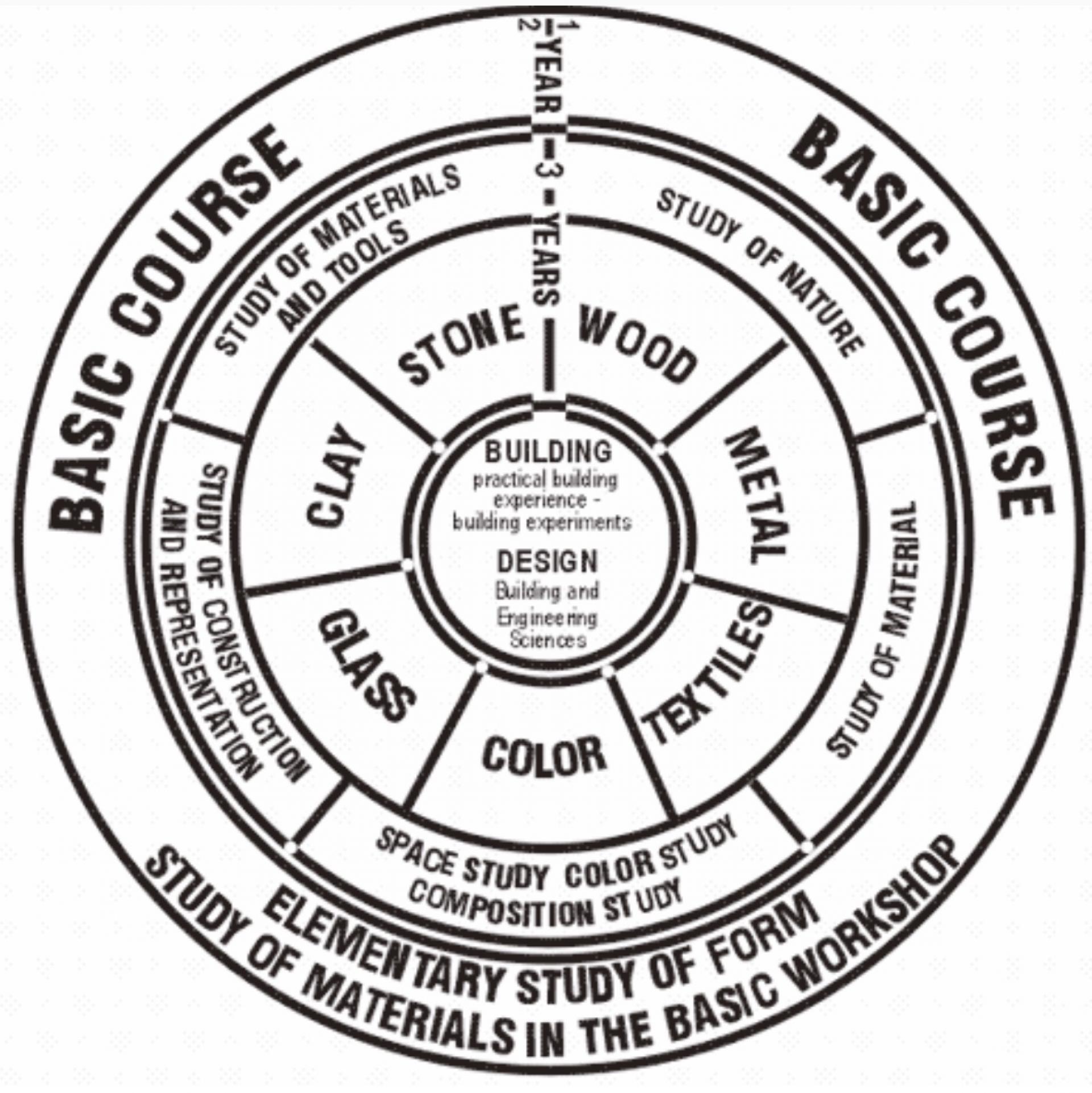

Bauhaus school was creating a nucleus of interdisciplinary innovation, which combined craft and design. Rather than utilizing the traditional model of teacher student relations, Bauhaus fostered community as the foundation of learning. Part of this ideology was also the integration of women artists in this community.

But Gropius also believed that men and women’s brains operated differently, men had the capacity to think in three dimensions while women not. Therefore many of women artists of the Bauhaus movement stuck to practices commonly regarded as women’s work, textiles and weaving. Men, on the other hand, become architects, sculptors and painters.

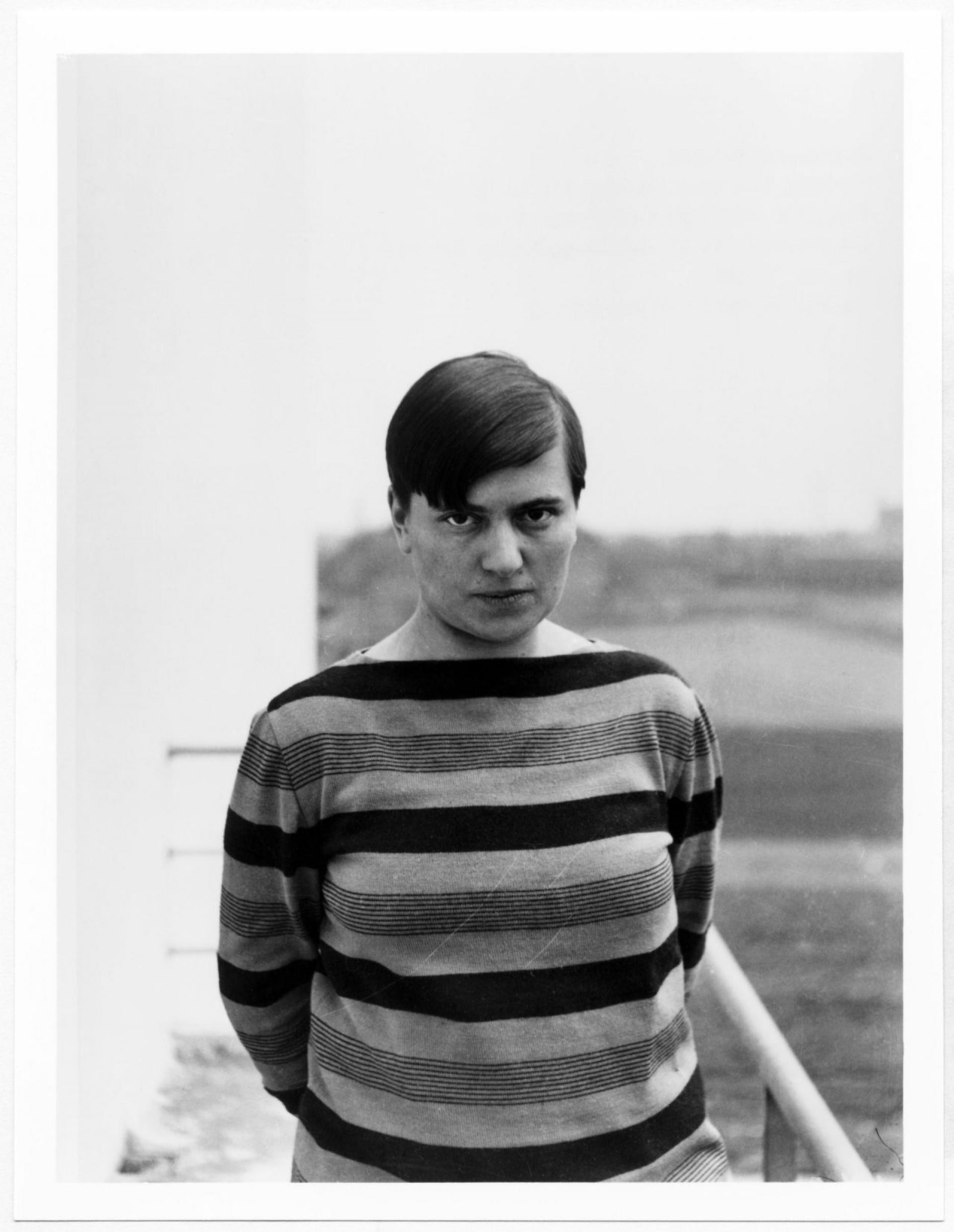

Otti Berger was a textile artist and weaver. | Photo by Julia Moholy-Nagy (1927)

A core member of the experimental approach to textiles, Otti Berger, experimented with methodology and materials during the course of her studies at the Bauhaus to eventually include plastic textiles intended for mass production. Along with Anni Albers and Gunta Stözl, Berger pushed back against the understanding of textiles as a feminine craft and utilized rhetoric used in photography and painting to describe her work. During her time in Dessau, she also wrote a treatise on fabrics and the methodology of textile production, which stayed with Gropius and was never published. Berger is the only designer from Bauhaus who sought patents for her textiles and became a deputy to designer Lilly Reich in the textile workshop at Bauhaus.

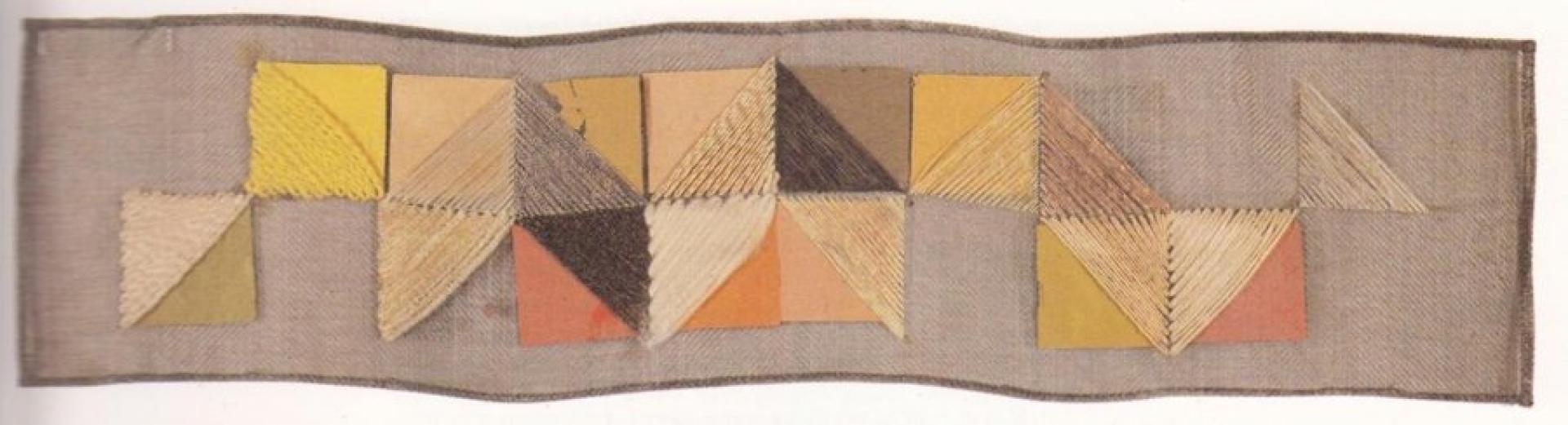

Otti Berger and Atelier Dessau by Lotte Beese (1930). | Photo Jeanine Fiedler

Not allowed to work in Germany under Nazi rule because of her Jewish roots, Berger closed her company down in 1936 and fled to London, where attempts to emigrate to United States to work with her fiancee Ludwig Hilberseimer and other Bauhaus professors failed.

Otti Berger’s Tactile Board (1928). | Image © Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

One of the first women who join the Bauhaus Department of Architecture in 1927 and the first to study with Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer was german architect and urban planner Lotte Stam-Beese. She worked on the reconstruction of Rotterdam after World War II.

Lotte Beese built Pendrecht, the first car-free street in Rotterdam as well the Netherlands (1947). | Photo via Architectureguide

After the second World War the influence of Bauhaus developed in the US. One of the pioneering designer and entrepreneur who created the modern look of America’s postwar corporate office was Florence Knoll Bassett. She studied under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Eliel Saarinen and worked with leaders of Bauhaus, including Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Wallace K. Harrison.

Florence Knoll promoted the Modernist merger of architecture, art and utility in her furnishings and interiors, especially for offices. | Photo © Knoll Archive

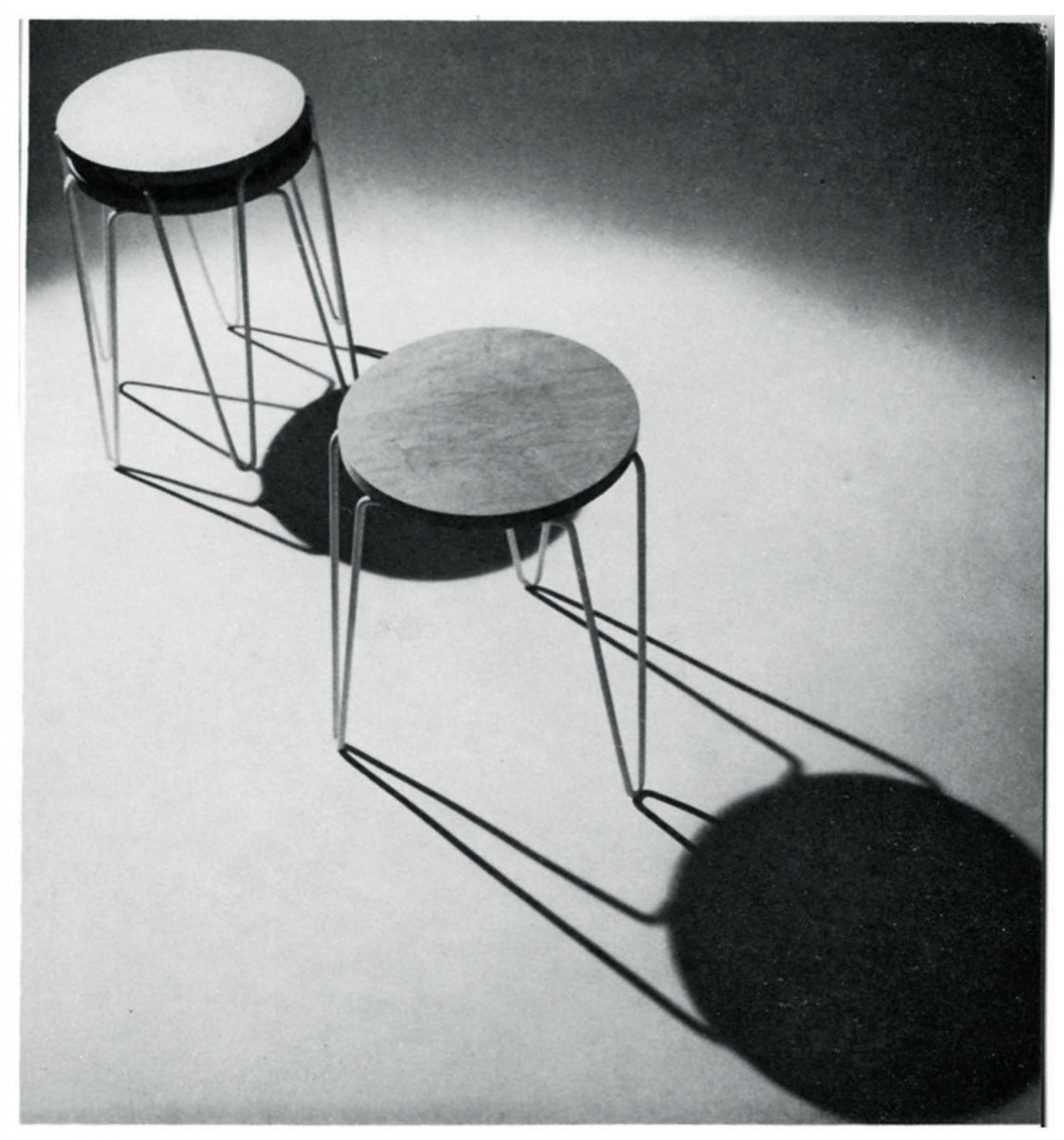

The Hairpin Stacking Stool designed by Florence Knoll. | Photo © Knoll Archive

The influences of Carl Koch, Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe are evident in many of Gertrude Kerbis’s designs. In 1954 she received her master degree from the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Peterhans.

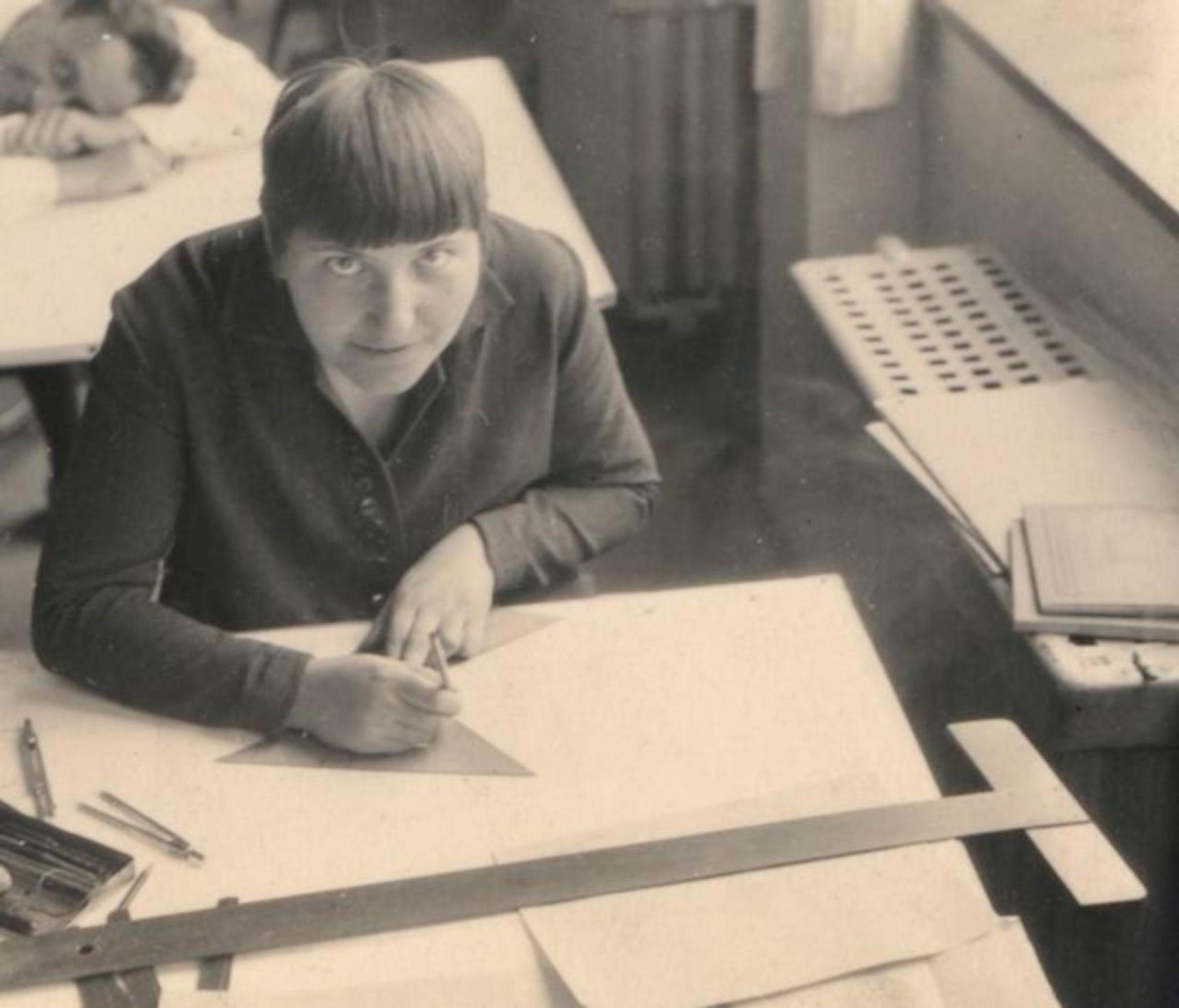

Gertrude Kerbis was a couple of decades ahead of her time; a woman in a sea of men wearing white shirts and ties. | Photo via Vimeo

Kerbis began her career when women at architecture firms were receptionists or secretaries. To change that she founded the Chicago Women in Architecture in 1973. She played a leading role in designing several major examples of American modernism, including the Lustron houses, the US Air Force Academy and the O'Hare International Airport Rotunda.

The dining hall’s interior of US Air Force Academy was column-free with a roof of steel trusses supported by sixteen columns. | Photo via Docomomo

Marianne Brandt, a strong and independent New Woman of the Bauhaus, was one of few women who distanced herself from the fields considered more feminine at the time such as weaving or pottery.

Brandt’s designs for metal ashtrays, tea and coffee services, lamps and other household objects are now recognized as among the best of the Weimar and Dessau Bauhaus. Further, they were among the few Bauhaus designs to be mass-produced during the interwar period, and several of them are currently available as reproductions.

Coffee and tea set by Marianne Brandt (1924). | Photo by Lucia Moholy

The modern women Alexa von Porewski, Lena Amsel, Rut Landshoff, unknown before 1929. | Photo by Umbo and Paul Citroen, Berlinische Galerie.