Curating An Exhibition In 2020: Handle With Care

Architecture exhibition Handle with Care: Tales of the Invisible opens at the Lisbon Architecture Triennale on October 15, as part of this year’s program of the Future Architecture Platform. To mark the occasion, here’s the interview with Sonja Lakić, architect, researcher and curator of the exhibition.

Preparing the exhibition at Lisbon Architecture Triennale headquarters, August 2020. | Photo © Sara Battesti

As we’re approaching the winter season of the pandemic which has pushed the entire world into various forms and intensities of isolation, it seems like there could hardly be a better time to reflect upon the practice of care and its relationship to architecture. Our rooms are becoming our worlds. When you began dreaming up this exhibition, did you anticipate it opening in this context of increased awareness of the spaces we inhabit?

SL: Absolutely not. The only spaces that curating this exhibition was supposed to unfold in, apart from Lisbon Architecture Triennale headquarters, were, obviously, interiors of Future Architecture platform partners institutions that I was, as it was originally planned, about to visit last spring. I would also add interiors of airports and airplanes to the list. Hotels included. I am still curious about all the breakfasts I missed due to pandemic. I, obviously, ended up making my dreams happen in front of my screen, meeting people sitting in front of their own laptops and/or computer screens, mostly inside their homes around Europe. I vividly remember the variety of blankets, cozy sofas and afternoon naps that violently came to an end due to numerous online meetings across Europe, as well as scaffolding outside an apartment in Turin that reminded me on L’Aquila, where I completed my PhD, planting a garden on a rooftop terrace in Lisbon, dilemmas from Berlin, and, finally, being taken next to a window in Barcelona to clap and support all the caretakers. I dreamt inside all of these homes without stepping inside any of them, appreciating them as the new landscapes of care, and, finally, landed in Lisbon: we are all, obviously, still in the mode of the increased awareness by all means, yet, the exhibition will get you covered from A to Z. It is, after all, handled with care.

Space Which Meditates: Future Architecture Accessories | Photo © Sonja Lakić

How did your background in architectural research and your lasting interest in lived forms of buildings inform your work on curating this exhibition?

SL: I am somewhat a dissident from the discipline: I work visually, yet, I operate at the scale of the everyday, chasing after the non-evident and doing the storytelling by often using the language of urban anthropology and urban ethnography. I do not believe that architecture is only a physical matter: there is more to the story than meets the eye. That being said, there was only one way to curate the “Tales of the Invisible”: zero concrete. Zero final solutions. Hardly any material architecture. From the very beginning, I knew there would be no space for the permanently built structures: instead, I, again, chose to focus on the human clay and bring different people and thinking experiments to light. I searched for different concepts and ideas, digging deep for passion and determination, attempts and failures, individuals and groups that once made the architecture world turn around, traveling back and forth in time, myself unlearning what architecture may (not) be. There is never a wrong moment to celebrate humankind and this exhibition is, to a certain extent, an excuse to do so: a gentle reminder of what still surrounds us and what we are made of, or, at least, once were.

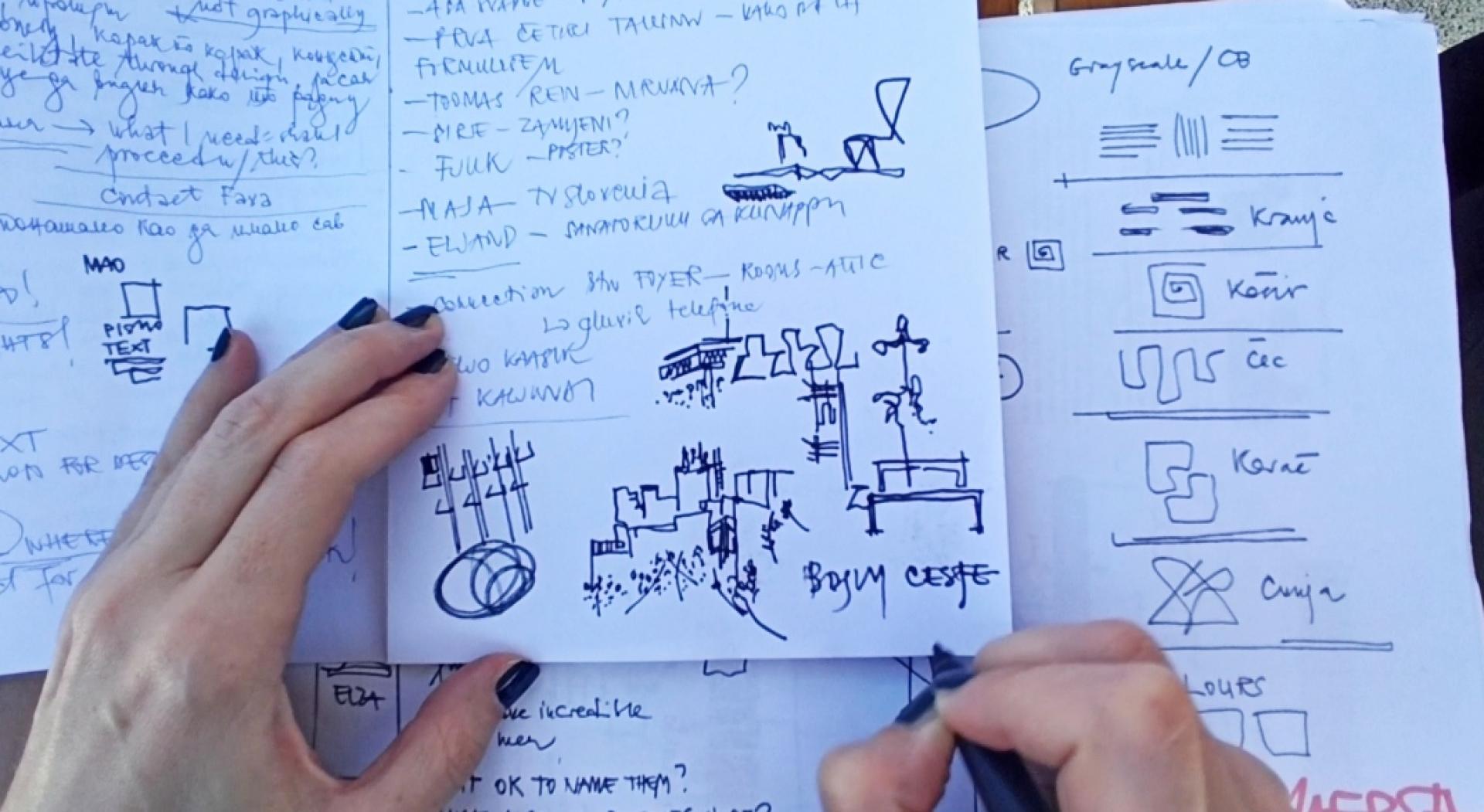

The creative process: keeping it as analogue as possible. | Drawings and photos © Sonja Lakić

In your curatorial statement, you refer to this exhibition as to “homage to the quirks of the human mind”, “a call to re-think where we stand” and “a gentle reminder that life comes before buildings”. Can this be interpreted as an invitation to (re)consider the political role of architecture?

Sl: I, most of all, envisioned the exhibition as a conversation, or, more precisely, a call for heart-to-heart exchange of this kind: my intention and desire is that people experience it and understand it in a variety of ways, yet, in full accordance with who they genuinely are. I never aimed to reach a consensus of any kind since that would mark an end of any debate. I, therefore, thank you for this question: I am more than happy to see that, days prior to the opening, the exhibition already lives its purpose by being interpreted. Thus, to a certain extent, the answer to your question is: yes, this is also an invitation to (re)consider the political role of architecture. What, for example, influenced my curatorial approach is “the awareness to the wonders” that Alberto Pérez-Gómez believes and, moreover, propagates in the book “Built upon Love: Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics”: we, whoever we may (not) be, should develop and nurture this skill that I interpret as “to stop and smell the roses”. This exhibition does this as well. Referring to your question, I have to say that I, obviously, find architecture political and this is, with no doubt, where consensus is inevitable.

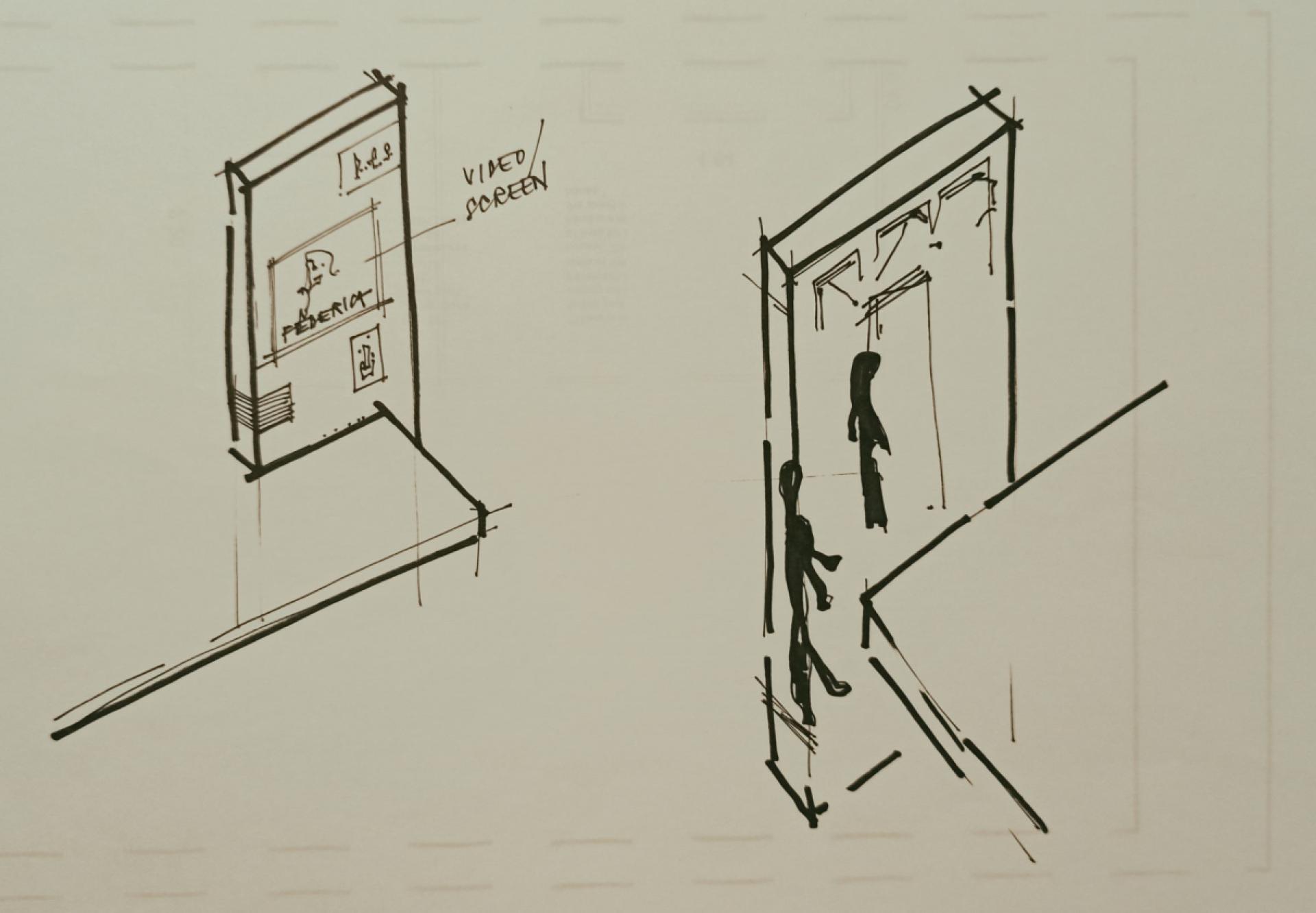

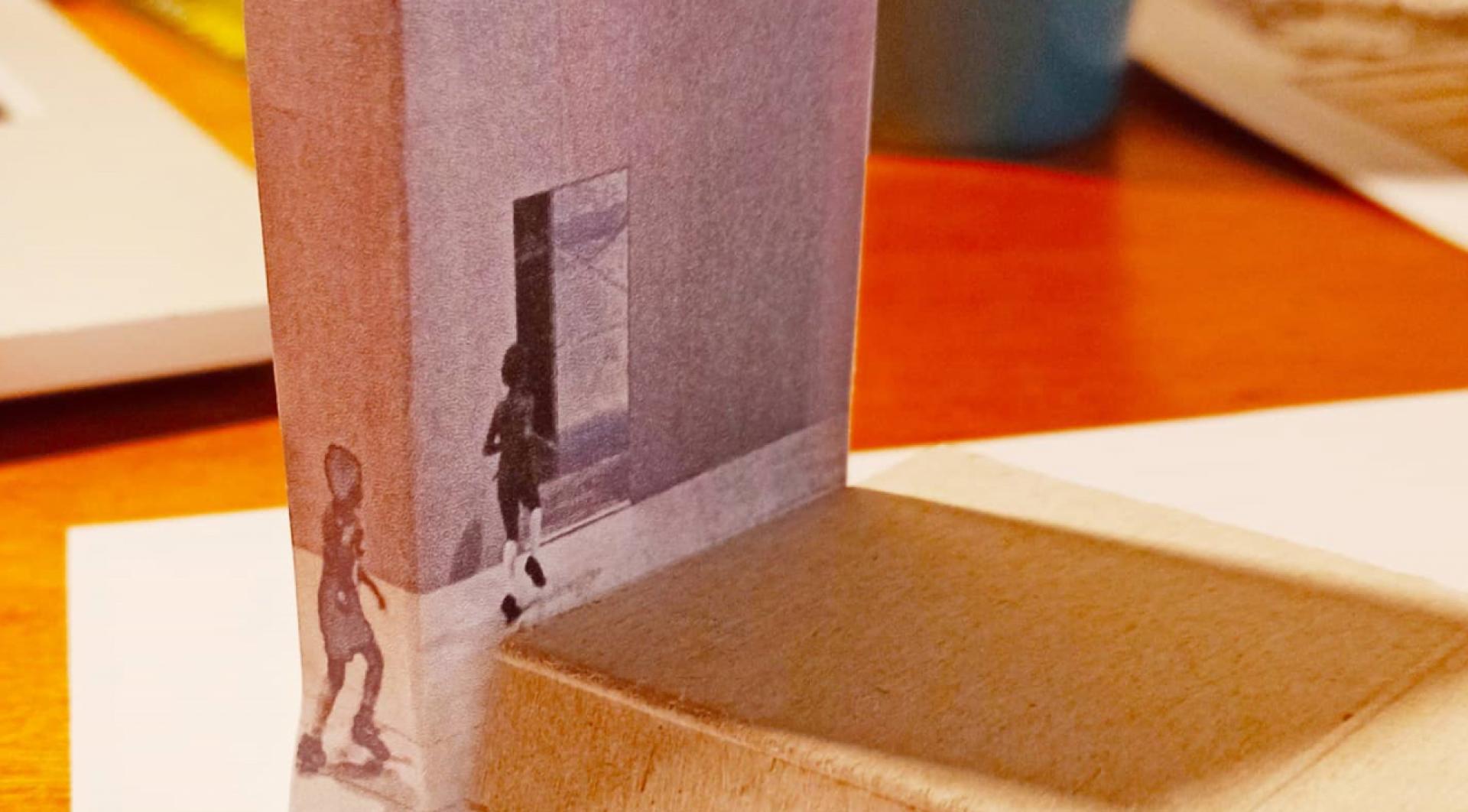

Creating models from a discarded box of chocolate cookies | Photo © Sonja Lakić

Can architecture amplify the human potential for care-giving and care-receiving, and if so, how?

SL: I believe that architecture itself stands for the noble discipline of care. This is why I, once upon a time, decided to study it: I recognised it as an opportunity to care about people while never letting go of mathematics, arts and drawing. For a nerd like me, to be engaged in this wide spectrum of disciplines is even nowadays of crucial importance, and was, therefore, as equally important during the early university days of mine, when I managed to detect traces of psychology and sociology in very few courses I was enrolled in.

Architecture, most of all, is all about a very particular responsibility that first comes with the vision of an architect and next translates to “a program” of how to use a building: this is where one needs to be very careful, while, simultaneously, to care a lot. The program is, say, often a recipe for how to live one’s life, as prescribed by an architect: of course, this rarely happens, for the life itself is not to be tamed. Architecture already amplifies the human potential for care-giving and care-receiving. Or, should I say that there are architects who do so? Maybe that would be more ethical. There are beautiful individual minds and collectives who stand for care by their mere existence, embracing their ethics in their texts and variety of programs. To paraphrase Esra Akcan, one of my favorite minds of all times: architecture can heal. And I believe it should. The process of healing may happen through the process of (un)learning, collaboration with other disciplines, seeing the world through the eyes of the other, while, simultaneously, never ever considering anyone as the other. Same goes for care.

Taking a break in the summer of the 2020: the Sun, the ocean, the drinks, and the disinfectant gel. | Photo © Sonja Lakić

What, however, instantly comes to my mind when thinking about architecture and care, especially the healing process, is whether it is possible for the healing of post-conflict societies, including the country of my origin, that is, the region of former Yugoslavia, to happen via architectural programs that, to put it simply, celebrate life. What if, instead of constantly exposing one to memorabilia that recalls past events and somewhat advocates for the culture of mourning, we take care of people by gently reminding them of all the reasons why it is good to be alive? I am aware that this is somewhat calling for a revolution, yet, this is how “the awareness to the wonders” I previously mentioned may be attempted to achieve, without any actual construction happening: this is where temporary structures, installations and performances and engaging in performative planning and tactical urbanism, could play an important role. We owe it to ourselves, as well as to each of our individual human potentials, regardless of who we as individuals are, to, at least, try, having a little faith in architecture as an event rather than the final say.

Sonja Lakić at Lisbon Architecture Triennale headquarters, August 2020. | Photo © Sara Battesti

The exhibition draws from the collections of the Museum of Architecture and Design in Ljubljana, MAXXI National Museum of 21st Century Arts and the Estonian Museum of Architecture. What does curatorial collaboration with museums scattered across Europe look like in a time of Covid-19?

SL: On the one hand, it resembled any other “new normal” kind of experience and, in that sense, it was not any different from any of the pandemic-imposed daily routine since it evolved around the absence of movement and the impossibility of touch. Simultaneously, it was quite a challenge: can you imagine curating an exhibition without stepping into an institution and getting to see a collection? I did dig deep within myself, looking for answers, and have to admit that, occasionally, it seemed to be a bit of a challenge. However, I have to say that I am immensely grateful to all the people that I crossed paths with and whom I collaborated with on this project: words are not enough to describe how easy and smooth the overall process was and how helpful, patient and caring were partners from Ljubljana, Rome and Tallinn. I learned a lot and indeed grew, yet, not only in professional terms: rather, collaboration with Museum of Architecture and Design in Ljubljana, MAXXI National Museum of 21st Century Arts and the Estonian Museum of Architecture had a profound impact on me personally as well and was, in this sense, a game changer. They were all extremely devoted and committed, helping me connect with architects and scientists that I, prior to this exhibition, have only read about. Oh, I went places I never dreamed of, and I will come back for more, however, in person. Hopefully no more screens.

Lisbon people and their balconies. | Photo © Sonja Lakić

A while ago, you stayed in Lisbon as a visiting researcher at ISCTE-IUL; now you’re back to curate an exhibition commissioned by Lisbon Architecture Triennale. What about the city preoccupies you these days? If Lisbon, as a living archive, could preserve one message from this exhibition, what would you like that message to be?

SL: People. People always preoccupy me regardless of my geographical location. I am currently collaborating with ISCTE-IUL again and am also affiliated with ETNO.URB, so there are many big fishes to fry, and I am extremely happy and beyond excited for this. Of course, I could not help it: again, I observed the Lisbon edition of glazed balconies, and I found that one of them is especially dear to my heart, as it conceals the story about the most notorious apartment in the 1980s neighborhood where I found my home.

As far as the message, I would say it is rather evident: life comes before buildings. People first. Always and forever.

-

by Sonja Dragović

Sonja Lakić (1983) is an internationally trained architect and researcher with a PhD in Urban Studies. Her work evolves around open architecture and dialectical urbanism, with a keen interest in lived forms of buildings hence anthropological and sociological aspects of architectural design and the built environment. Topics of her curiosity that she nurtured in Gran Sasso Science Institute and while briefly appointed as visiting researcher at ISCTE-IUL in Lisbon, include the everydayness of architecture, home(making), housing and informality, buildings as living archives, post-conflict societies. Sonja operates across different disciplines and scales, works visually, and collects oral histories, practicing unconventional ethnography and storytelling mainly through photography.