Othernity

Interview with Dániel Kovács, the curator of the official exhibition of the Hungarian Pavilion at the 17. International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia.

Interior of the Calvinist church of Külső-Kelenföld, Budapest (1981) by István Szabó. | Photo Dániel Dömölky (20209

“In Central and Eastern Europe, modernist post-war buildings - relics of socialist modernism - are in an increasingly threatened position. Their situation in Hungary is becoming more and more politicized: seen as remnants of the communist past, they have no future, and are demolished or refurbished. The architectural heritage of a whole generation is getting lost,” starts the curatorial statement of the team behind this year’s Hungarian Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale. Dániel Kovács, the curator of the pavilion explains that “to this day, theory and practice of our modernist forebears is an important intellectual ammunition for architects, but more importantly, these buildings were once the backdrop of our everyday lives, and they are still objects of personal attachments and memories. Instead of erasing them out of our memory, we should finally come to terms with our past.”

“Othernity – Reconditing Our Modern Heritage”, interior of the exhibition at the Hungarian Pavilion of the 17th International Architecture Exhibition in Venice.| Photo Dániel Dömölky (2021)

The Hungarian project exhibited in this year, titled “Othernity – Reconditioning Our Modern Heritage” tries to look for possible answers. On this occasion the curatorial team of architecture historian Dániel Kovács and architects Attila Róbert Csóka, Szabolcs Molnár and Dávid Smiló invited 12 architectural practices from nine countries of the region with a mission to outline the future of 12 selected modern buildings in Budapest. “They offer different approaches and perspectives, but the collective results make one point clear: in a sustainable and responsible way, our future can only be built on our past,” concludes Kovács. The pavilion features A-A Collective (Poland / Denmark / Switzerland), Architecture Uncomfortable Workshop (Hungary), b210 (Estonia), BUDCUD (Poland), KONNTRA (Slovenia / North-Macedonia / Croatia), LLRRLLRR (Estonia / United Kingdom), MADA (Serbia), MNPL Workshop (Ukraine), Paradigma Ariadné (Hungary), PLURAL (Slovakia), Vojtěch Rada (Czech Republic) and Studio Act (Romania).

In the curatorial statement you are pointing to overcoming the aforementioned neurosis of Eastern and Central European people within sharing the collective optimism phrased by participants; is that the Othernity?

Dániel Kovács: The identity of this region, Eastern Europe, is an unnatural, political one, created by the invading superpower after WW2. They got stuck, Western media started to use it, but became filled with negative connotations. If you think about Eastern Europe, you associate it with slightly uncultured, tribal people, physical workers, and nonintellectuals. In the early 1990s we actually tried to change these connotations and come up with the concept of Central Europe, based on the German concept of Mitteleuropa. But it turned out that nobody was interested in this. We remained Eastern Europeans. Today there is an attempt to re-appropriate this term by our generation, the ones who grew up after the change of the regime. We are trying to fill this with new meanings.

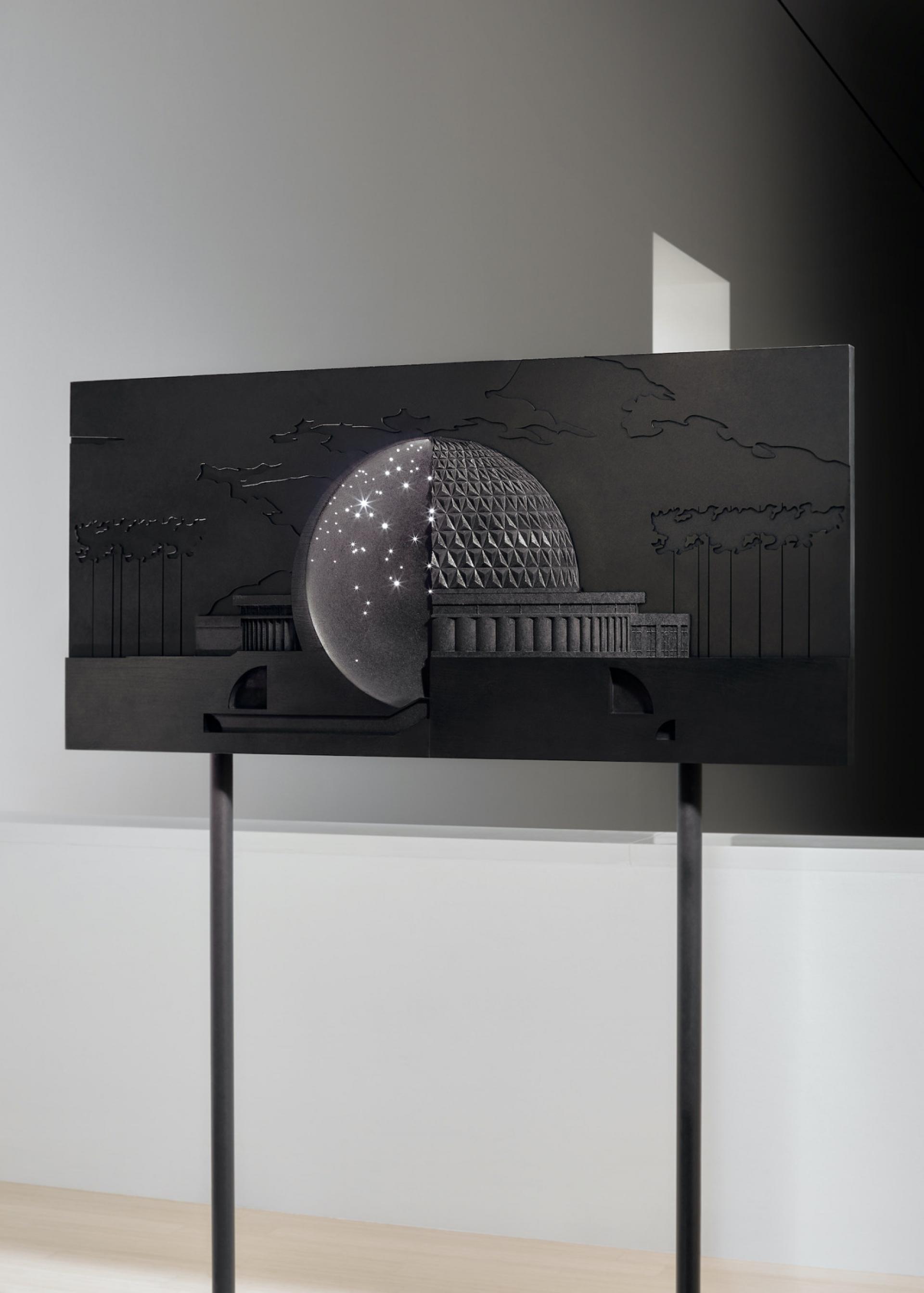

LLRRLLRR: Stars, Dead Bodies and Other Forms That Do Not Change - installation. | Photo Dániel Dömölky (2020)

So in this sense the neurosis is the feeling that our identity was imposed on us from the outside and what we are trying to do with Othernity, an architectural attempt, is to fill it with a certain kind of optimism. The expression of collective optimism came up in our first personal meeting with the participating architects in November 2019. The first time, when we sat down together with architects from 9 different countries in the region, we realized that it is so easy to understand and talk to each other because we share the same backgrounds, the same historical and social experiences. That leads us to define this feeling, this atmosphere as collective optimism that can replace the present neurosis.

Othernity is also a very provocative name, how is your statement accepted by the culture politics in Hungary?

DK: Obviously the whole concept came from a recent problem, modernist buildings are being demolished not only in Hungary but basically everywhere. In this region there is a certain factor that contributes to this process of demolitions and that is the political aspect. Buildings from this period in the region are seen more as relics of this communist past. But everything is over politicised in Hungary, because this is what populist politics do, they overpolitisise every aspect of life. As a gay man I’m laughing all the time when it comes up that I “should keep my private life in my bedroom”. I would like to do it but it is impossible because my bedroom is full of politicians who are trying to control my private life. On the other hand however this is a very clever tool by populist politics, that politicizes everything and forces people to be either indifferent or take up a political point of view.

KONNTRA: Mo·nu·ments - installation | Photo Dániel Dömölky (2020)

What about the Hungarian media?

DK: Unfortunately, the media also takes over this tool from politics. Not only Hungarian but also Western media shows news from Hungary in a strictly political point of view. We are always represented as people in connection with politics and nobody does anything to change this point of view. This is a problem that works against an united Europe. Most of the people from this region don’t feel as part of the united Europe because we are always represented as different. Actually this debate and this situation is very similar to the debate about colonialism and to the representation of African and Asian people. But nobody understands that the same is happening with us Eastern-Europeans. We are represented in a way that we don’t identify with. And we can not do anything about it.

In which sense?

DK: Whenever I am reading English press it is very funny to see how keen they are to use certain foreign language expressions, like for example taoiseach, the name of the prime minister of Ireland or certain expressions from the Maori language in New Zealand. On the other hand whenever they are writing down the name of anybody coming from Eastern Europe, they never use the proper accents and punctuation. Nobody is using the both two accents in my name, as they think it is not necessary. But that is not my name, I want my name back. What the Othernity project is about is that we would like to re-appropriate our identity to fill it with a meaning, which is defined by us. And believe me there is nothing political about it.

To answer your previous question shortly, surprisingly we have no political reactions coming from cultural politics. Obviously the concept was debated in Hungary, but it wasn’t politicised as much as I expected to be.

MADA: 1.250.000 m³ - installation | Photo Dániel Dömölky (2020)

Can the Othernity be perceptive as an utopia that generates new collective ways of living in the region?

DK: I would hope so, obviously, but I don’t expect us to save the world. What I expect and what I am working on is to create discussion. To open up people’s minds, either Hungarians, people from the region or people from other parts of the world. To help them understand these problems and recognize their own problems, reflected by ours. In this sense Othernity is a bigger success than we expected because many people in Venice from different parts of the world came to the curatorial team and examined the problem, discussed its origins and questions engaged in lively discussion. This was great feedback, which we really didn’t expect. So many people would recognise their question and problems in this quite specific attempt.

Participants and curatorial team of the Othernity project. | Photo József Rosta, Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art (2019)

What were the criteria for the selection of twelve practices from the region and how did the process of collaboration run?

DK: First we have chosen the twelve buildings in Budapest and then we researched in our networks for international partners. This was way before the competition because in Hungary the biennial curatorialship is decided by an open competition. When we won our curatorial enrollment we already had everything finished, we even had the first ideas from the architects. This was six months of work before the deadline. As I mentioned we wanted to reach out to those who are in their twenties, thirties, early forties and who grew up and were educated after 1989. They are already citizens of Europe and they identify as Europeans but share the same experiences and architectural heritage. By this they would understand what these buildings in Budapest could mean and could represent for Hungarians and yet they have an objective distance. The original idea was to represent both sides of the story, with the historical aspect, buildings with their documents and the archive materials in one hall of the exhibition building in Venice and on the other hand, the proposals, the twelve new ideas. This created a mirroring structure, which we manage to keep throughout all the exhibition and even the catalogue.

How is modernist architecture accepted by the current Hungarian government?

DK: There is no general view on that. It is true that of the twelve buildings we have chosen, two have been demolished in the past year and one of them was demolished by the government. Another building is currently being considered to be demolished by an independent institution with governmental funds. When I approached them to ask about why this building is being demolished they answered that it is a brutalist building and it was the headquarters of the workers militia, a very communist organization. These kinds of arguments do come back again and again in these discussions, especially if you look in the context of the ongoing reconstruction of the Buda castle. I don’t debate the decision of the government, which is to reconstruct the castle in the pre-war state, against the current state built in the 1950s, 60s and the 70s. There is a certain kind of nostalgia from the part of politics towards the pre-war era and certain kind of hatred towards the post-war era.

Maybe also ignorance and prejudices?

DK: That’s the reason I wouldn’t try to point fingers on responsible parties. This is also a responsibility of the architectural community of the architectural historian community, because we were not able to develop canons, we were not able to come up with what’s good and what’s not good regarding modernism. Behind this inability to say anything out loud is again a general feeling of uneasiness and uncertainty, which is nowaday present in every aspect of our lives. Who is to say that one building is good? Who is to say that we should keep this building instead of the other? There is no hierarchy anymore. What Othernity is trying is to figure out how to keep discussing this topic. To show that architects do have the creative thinking necessary to solve these problems. I think these twelve different approaches in the pavillion really prove that young architects are capable to come up with ideas that can push forward certain problems.

Do you think that architecture and culture fight can change political borders and create new identities in the geopolitical space of Eastern Europe?

DK: This could happen everywhere, not only in Easten Europe, but I wouldn’t use the term fight. I think these are tools to use. It Is not a coincidence that we came up with the expression reconditioning, because it’s a psychological expression and not used in architecture. If we want to change these situations, we need to change our ways of thinking. For that we need to recognise, realise certain very basic problems such as overpolitisizing architecture, dealing with the constructing identity, recognising our neighbours and start to talk to them. If we are able to do that we can change what’s happening and we can affect what’s happening in architecture and culture but only if we are able to recognize these things.

The curatorial team of the Othernity project: Attila Róbert Csóka, Szabolcs Molnár, Dávid Smiló and Dániel Kovács. | Photo Dániel Dömölky (2021)

The Othernity is a new, collaboration-based method, which helps us rethink our practice of heritage protection and, at the same time, it is such an architectural behaviour that can create a more responsible attitude towards profession and society. The Hungarian Pavilion is looking for an answer to the following question: what possibilities does the often disputed and in many ways obsolete heritage of modern architecture hold for the architects of the future?

The curatorial team asked 12 architecture practices from Central and Eastern Europe to recondition 12 iconic modern buildings of Budapest, offering a possible way to reconcile past and future architecture.The selected buildings of Budapest were built during the socialist regime, and in spite of their values, they are in danger today. The invited architects from Central and Eastern Europe know and understand the dilemmas concerning the conservation of the regional architectural heritage, however, they already studied and gained professional experience in the united Europe and one the characteristics of their projects is the experimental attitude pointing towards an international direction, which is accompanied by a fresh visual form of expression.

The exhibition is divided into two spaces: the LAB section documents the historical conditions of the 12 buildings, while the SHOWROOM section presents the 12 contemporary architectural reflections. Othernity is the first exhibition project in the history of the Hungarian Pavilion based on wide-ranging international collaboration. At the same time it is a collaborative practice, research on heritage protection and the expression of our conviction that the architecture of the future can be built on the past in order to reach due resilience, adequate sustainability and strong identity bonds.