New Digital Architectuul Fellows: DAF

Learning, Interacting and Networking in Architecture, shortly LINA, is a new European architectural platform coordinated by the Faculty of architecture in Ljubljana. A network connecting prominent cultural institutions with emerging practitioners steers the architectural profession towards sustainable, circular and clean practices with highlighting emerging voices. The LINA Architecture Programme is carried out by different architectural museums, universities, research networks, foundations, triennials, biennials, and other European and Mediterranean architectural organizations. It was born from the Future Architecture platform, created by the Slovenian architect, critic and curator Matevž Čelik.

Under the umbrella of LINA Architectuul will give the opportunity to several fellows under the programme Digital Research Fellowship to join the collaborative online architecture publication and work with Architectuul’s editorial team. I had the opportunity to talk with Architectuul’s Digital Research Fellows 2023 Tevi Allan Mensah, Meriem Chabani (New South), Laura Solsona and Eduard Fernandez (self-office).

What is your current focus in architecture?

Allan Mensah: Architecture has changed and it can’t be the same discipline as it has been for decades. We need to understand that architecture doesn’t necessarily mean to build, it can also be a discipline of communication and research. In such a way one of my main focuses is to research how architecture can become a means of communication.

Eduard Fernandez: I believe that an architect nowadays cannot do only one specific thing, and that thing cannot be just building. Bringing in other topics could help the architecture discipline to go further with its role within society, especially to open new conversations in other specific fields. In this sense, it is crucial to demand our public institutions to invest in research and culture through financing and new policies in construction, so this is the way new narratives and approaches can be explored. Our office is, in this sense, multidisciplinary: we enter competitions, we have a few private commissions, but we also do research and teaching.

Meriem Chabani: I prioritize vulnerable bodies and territories following the words of bell hooks by putting the margin at the center. I enjoy questioning power dynamics and stakeholder relations, looking for that space of freedom in-between, where my projects explore human practices to inform spatial resolution. In order to tackle the climate crisis, I also deeply believe in a decolonial approach centering overlooked knowledge, practices and bodies from the Global South.

How is your proposal for LINA dealing with such issues?

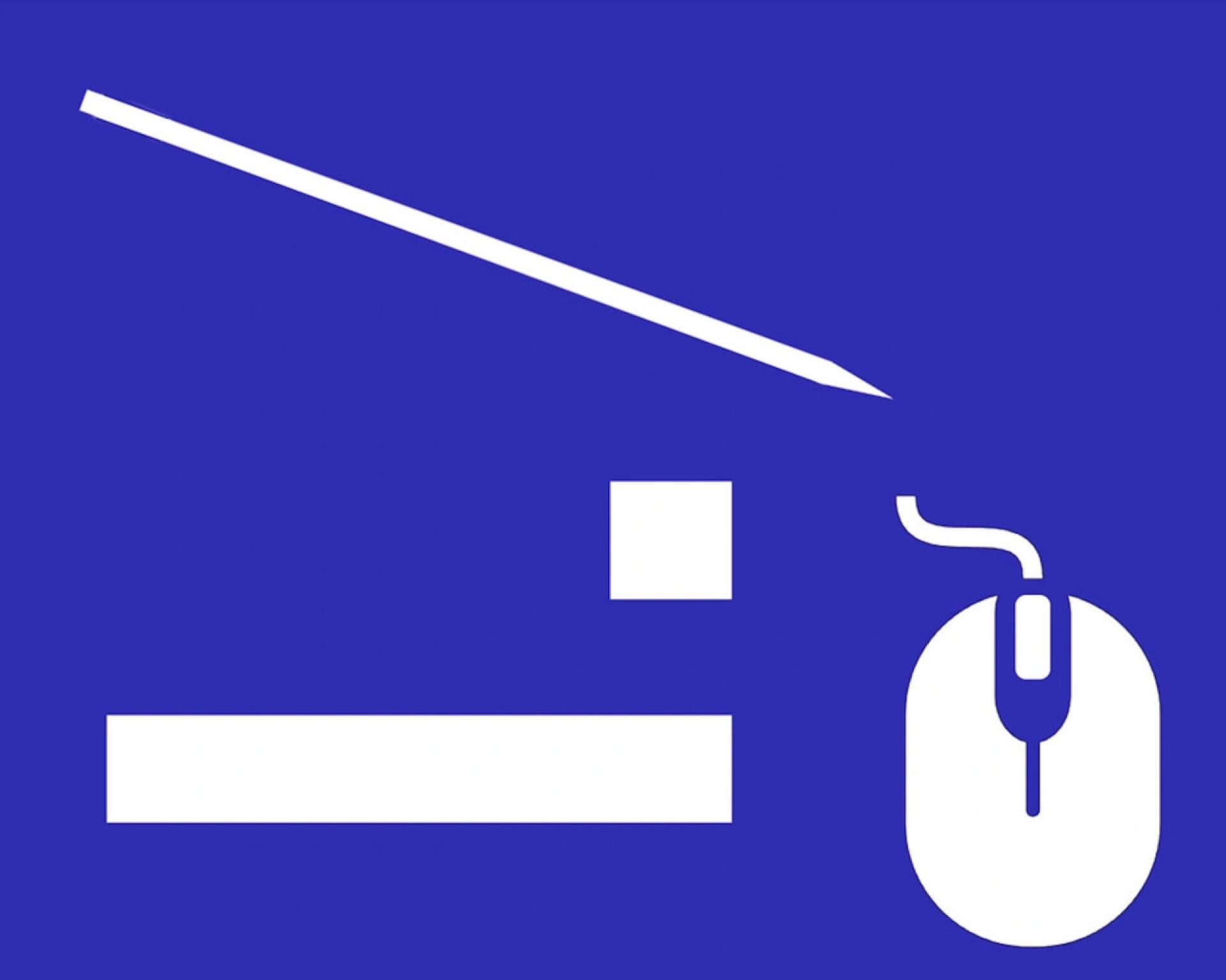

Allan Mensah: My visual research Borderlands has an idea how the border can be a territory of possibility and of opportunity for architecture. In such a way I can propose ideas to change the way people are perceiving different kinds of territories. Being an architect means creating borders every day with every line that you draw. Therefore I started to cut the word “border” in different synonyms, which creates different positions in architecture. In such a way borders can be displacement, thresholds, it can be an invisible, virtual border, a territory of heterotopy, it can also be a synonym of an island.

Island for a moving refuge. | Photo © Tevi Allan Mensah

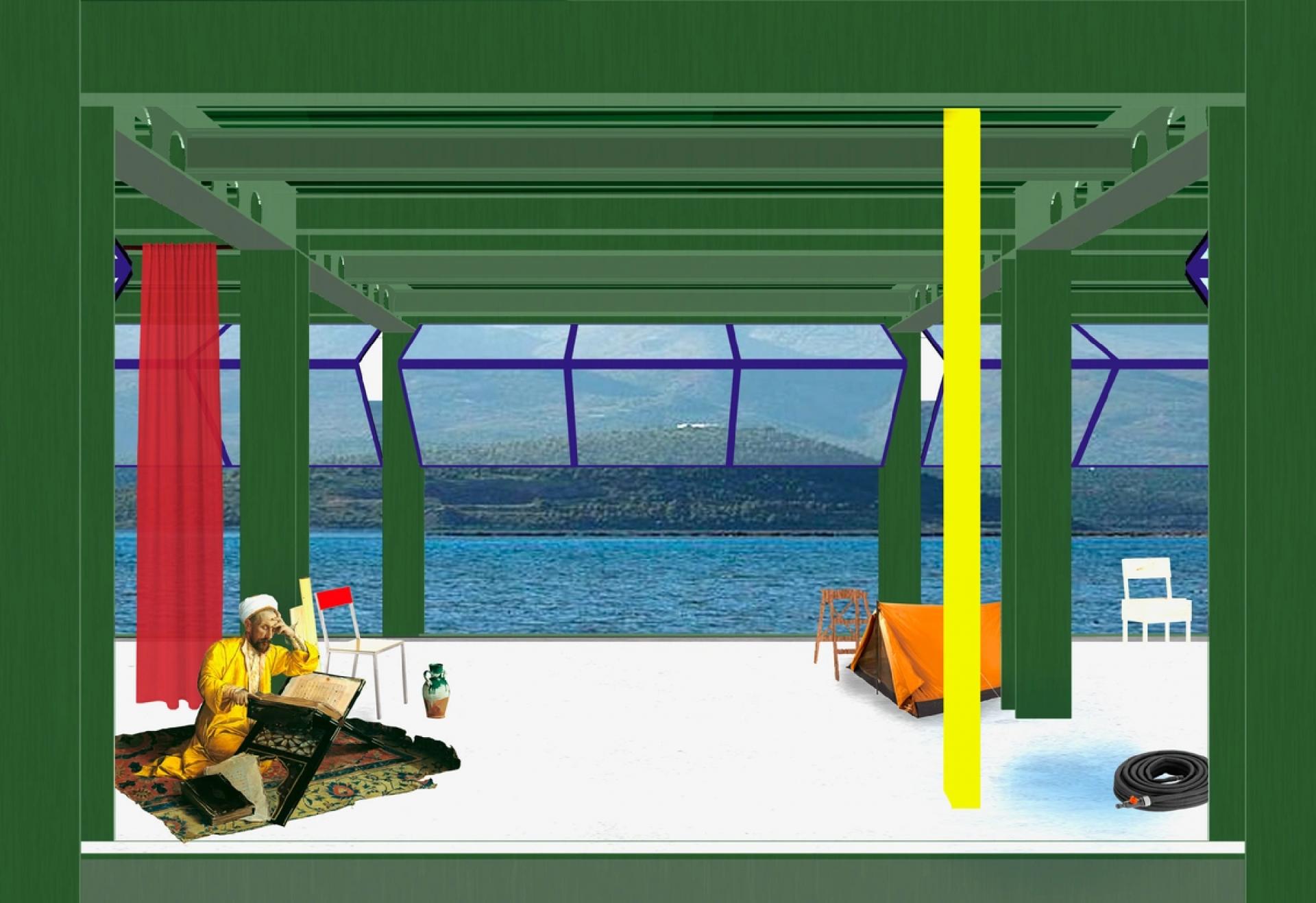

Meriem Chabani: The research Sacred Grounds is a call for cities to reinvest in the notion of the sacred, bringing about processes of care for the built environment. In secular societies, the sacred has all but disappeared from the urban realm. The buildings that embody sacredness - churches, mosques, and other places of worship - are increasingly removed from the city’s landscape, and stand, for the most part, empty. Elsewhere, monuments offer a rigid approach to collective meaning and memory - often shaped by political agendas - but overall, the urban realm in Western cities holds little space for that which cannot be defiled. In a nutshell, Sacred Grounds is about the restoration of a sacred covenant between people and place, to establish a framework for the creation of value outside of market price, fostering truly sustainable cities.

Could the notion of the “un-defileable” hold a vital significance in the age of climate emergency?

Meriem Chabani: An example can be found in the Algerian desert town of Ghardaia. Built on a hill, Ghardaia is an oasis town of brick and packed earth houses overlooking the Sahara. At its base, a few acres of palm trees grow, while at the top, a single palm tree stands across the mosque. For miles, the trees below and the tree above are the only patches of green visible. A few decades ago, the townspeople decided to expand the city outside of its historical walls and build new houses by cutting down the palm grove. In 2008, heavy rainfall resulted in a flood that destroyed hundreds of homes and killed thirty people. The neighboring town of Beni Isguen, which had preserved the trees growing on its border, was not affected. As a result, in Ghardaia and surrounding towns, the fundamental importance of the palm tree has been re-established. As Muslims, the inhabitants do not worship idols - to them, there is no god but God. Yet the palm trees, if they are not holy, are definitely sacred.

A prototype at CIVA Brussels, 2022. | Photo © New South

The story of Ghardaia teaches another lesson: to build a sanctuary isn’t to separate it from the urban landscape; it is simply a way to define, collectively, a priority that is absolute. From this perspective, sacredness could be an economic principle: by design, the sacred is what lies outside of the reach of human exchanges. If translated into the language of contemporary architecture, the sacred is outside of the grasp of unchecked real estate development.

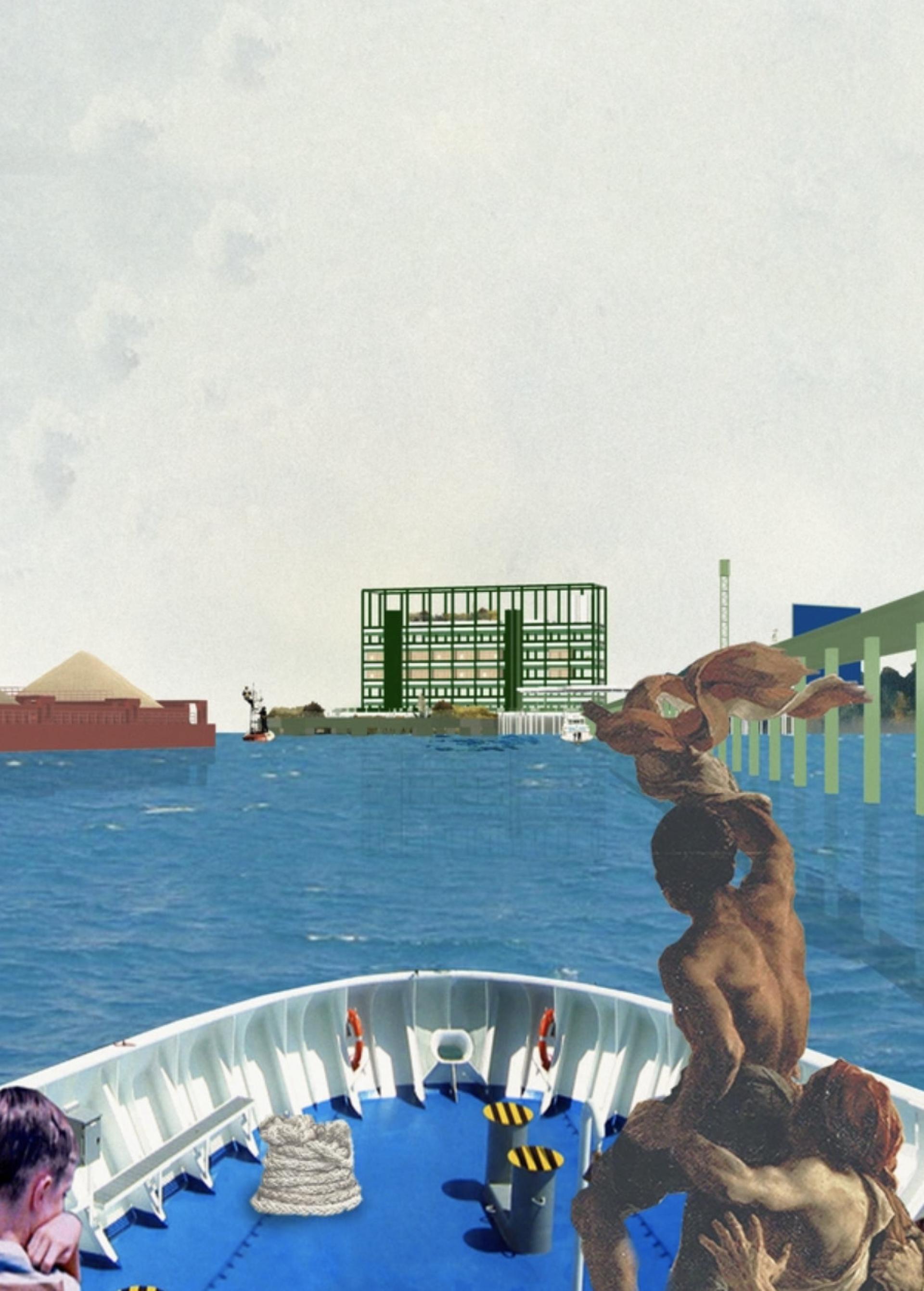

How did participation in LINA influence your work?

Laura Solsona: When Eduard and I moved back from Australia, where we worked for four years, we applied to LINA with the aim of establishing a network of people with similar interest in the European context. We believe LINA can offer us the opportunity to get involved in contemporary research projects and collaborate with peer architects from different disciplines. The research project Infrastructures of Resistance with use for the application to the LINA open call was produced in 2021 at the University of Technology Sydney. As tutors we did a design studio that investigated alternative forms of ownership to collective housing. Now the next step is to keep developing the project in other European contexts.

Project of the student Boris Mandić from Infrastructures of Resistance studio, University of Technology Sydney. | Photo © self-office

What do you expect from LINA?

Allan Mensah: Well, to be showcased on a European scale is for me a big opportunity because it offers me new connections and the possibility of creating my own network. LINA also changed the format of my research by understanding and learning from involved institutions' needs. It offers me new ways of learning especially with new tools, like being a digital fellow of Architectuul will help to understand and work in digital publishing. Digital publishing via Architectural is a territory of freedom that is completely new to me and I am really excited about learning brand new tools.

Where did you hear about LINA?

Eduard Fernandez: I heard about LINA via e-flux magazine because I’m subscribed to the newsletter. I knew its predecessor, the Future Architecture Platform, which I just found out it was formed by most of the same members, which is great. I hope that LINA keeps pushing young architects, editors, organizations, schools of architecture, museums, biennials and triennials to create alternative narratives and a new critical body of work.

What shall the architecture profession become/change in the future?

Allan Mensah: Architecture needs to be able to adapt to another position. As a profession it needs to be more honest and not try only to reproduce answers. In times of complete uncertainty we can’t be in the position that we know everything and we are able to solve all problems because we won’t change the world alone. My idea of the change is not in the way we work, organize, construct, but more the way we are.

Island for a moving refuge. | Photo © Tevi Allan Mensah

Laura Solsona: We believe that the figure of the architect that knows about everything and works alone does not exist anymore. An architect is a professional who can establish strategies and is able to coordinate the work in between disciplines. It combines different narratives and goals that take into consideration the limited resources, both material and economic, in each case scenario. Moreover, it is crucial to reframe education of architecture in universities. Shifting towards an educational model that puts the focus on collaboration rather than competition could start changing the attitude towards design and building.

Meriem Chabani: The architecture profession is likely to undergo significant changes in the future, mainly driven by the climate emergency, and shifts in societal needs and values. According to data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), the construction sector is responsible for approximately 36% of total energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions globally. Architects are, and will continue to be expected to design buildings that are more energy-efficient, environmentally friendly, and resilient. However, some argue for a more fundamental change, with Charlotte Malterre-Barthes defending a moratorium on new construction (2021). In industrial countries, tomorrow’s cities will mostly be today’s cities, with already densely built urban fabrics. Our industry might be wise to anticipate a shift towards greater care for what is already built, transforming, re-using and expanding on what is already there.

A pavilion calling for cities to reinvest in the notion of the sacred, bringing about processes of care for the built environment. | Photo © New South

Care in which sense?

Meriem Chabani: The standard body for which we design will hopefully also come into question. With increasingly aging populations in Europe and industrialized countries, how we accommodate the needs and care necessary for these bodies will become an essential driver of public policies. Overall, I think these changes are to be celebrated: let’s bring more care into architecture, more diversity both in how and for whom we design.

How hard is it to survive with architecture on today’s market?

Eduard Fernandez: As architects, we have been educated to provide a service to society based on economic growth. What we have learned recently after the Global Financial Crisis, and even Covid-19, is that we do not need new museums, hospitals, housing developments, etc. but rather a more specific approach towards the way we reuse what we have already built and a more sustainable way of living. All this is directly related to architecture, so there needs to be a market shift in this direction. Also, we do not need to build that fast as we have been doing in the last decades. Nowadays, the situation of our society is based on precarity (energy, housing, etc.) so we need to find alternatives to that situation.

Project of the student Boris Mandić from Infrastructures of Resistance studio, University of Technology Sydney. | Photo © self-office

In our office, we want to change the way we think and explain our projects, as we have been taught. New narratives that take into consideration sustainable construction methods, the reuse and recycle of materials and the circular economy. It is hard to survive economically when one has this ambition because it is time consuming, but that is our ambition.

Meriem Chabani: Obviously, this varies depending on the context, but if we’re talking about the construction market, we’re really talking about value. And in this equation, architects find themselves in unfavorable power dynamics. Mainly, what I see everyday are the following difficulties: a profit-driven construction market, with a growing private sector and ever-disappearing public sector; the increasing complexity of the construction process has given way to a specialization of expertise, and an increasing division of the fees associated with it, with small and young architecture practices struggling to keep up and restricted competitions that favor older practices and exclude younger or more innovative approaches.

Faced with an uneven playing field, I strongly believe that we cannot simply play by the rules. We need to understand the rules, the other players and their endgames. Then hack the game, disrupt it, play within and across it, shamelessly. Overall, the architecture industry is constantly evolving, and surviving in it requires a combination of technical expertise, creativity, business savvy, and grit.

Digital Architectuul Fellows 2023: Tevi Allan Mensah, Meriem Chabani (New South), Laura Solsona and Eduard Fernandez (self-office).