Salaspils: A Soviet Memorial To Nazi Victims In Latvia

Eighteen kilometres out of Riga, a series of stone giants stand frozen in a forest clearing to mark a place that some would rather forget.

The forested approach to the Salaspils Memorial.

The road to the Salaspils Memorial Ensemble stops near the rail tracks, and visitors must walk the final stretch – through forests of pine, and birch that in autumn explodes into canopies of red and gold, the sunlight slicing sideways between trunks that shed their crisp white bark like snakeskin.

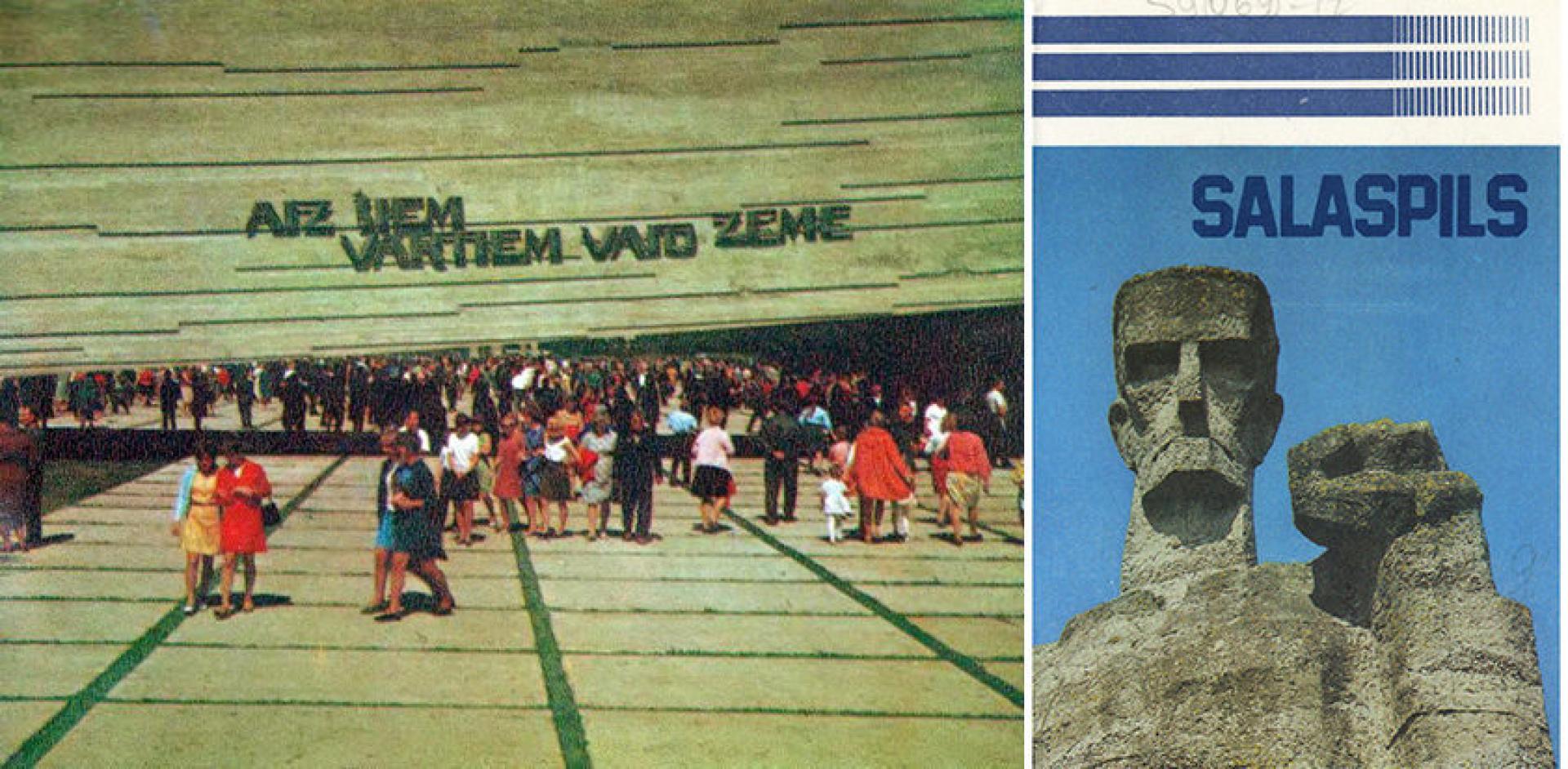

The gallery building measuring 100 metres long by 12.5 metres high.

In the clearing beyond stands the Salaspils Memorial Ensemble.

The forest feels alive, almost supernaturally so, making it all the more abrupt to find the path suddenly barred by a looming concrete crossbeam, 100 metres long and more than 12 metres tall. This concrete barrier is a visitor building, an abstract Brutalist gallery that marks the symbolic threshold between life and death. It stands in the place where once there was a guardhouse ringed in barbed wire, the entrance to a former Nazi labour camp that operated for four years here amidst the picturesque Baltic birch. Through the arch, a clearing opens up between the trees; the camp barracks long gone, to be replaced by angular Soviet forms, towering, blocky figures stood as tall as the trees that surround them.

Above the entrance, a Latvian slogan is spelled out on the concrete flank of the gallery “Beyond these gates the land groans”, a line from a poem, written by a former prisoner of this place.

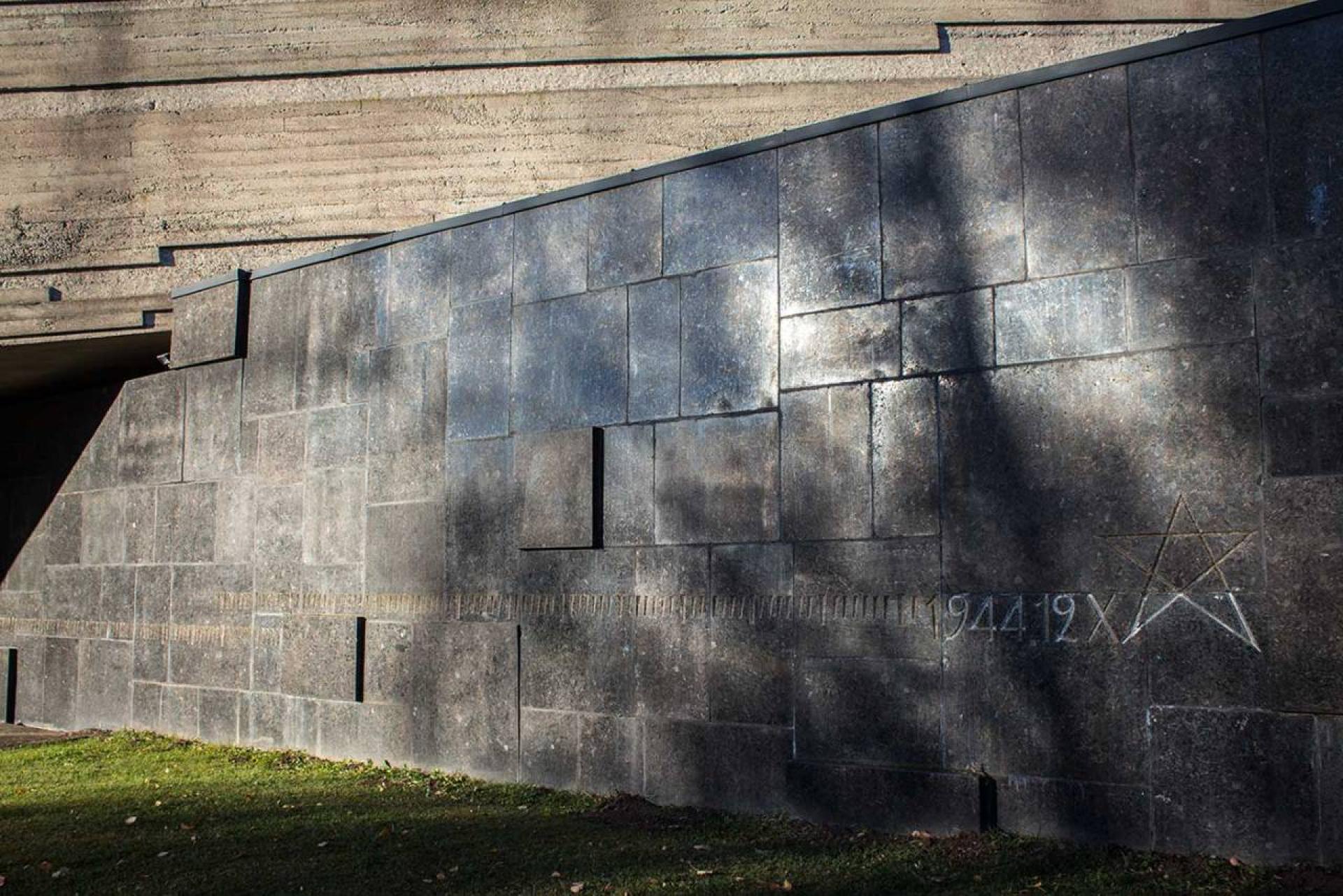

Part of the original wall of Camp Kurtenhof.

SS-Sturmbannführer Rudolf Lange, who was appointed in 1941 a commander of both the Nazi Security Service and the Security Police for occupied Latvia, that same year proposed the creation of a detention facility in the region. It was named Camp Kurtenhof, from the German name for the town of Salaspils, and located for convenience just off the main rail track between Latvia’s two largest cities: Riga and Daugavpils. It was designated a Police Prison and Labour Correctional Camp.

A symbolic tally etched into the gallery building counts time inside the prison.

Work on the camp began in late 1941, and it was built largely by the hands of Jewish prisoners deported from occupied Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. At least a thousand Jews were transported from the Riga Ghetto to join the construction team in January 1942. Offered little in the way of comfort, nutrition or sanitary facilities, they were overworked and many would die to that first harsh Baltic winter.

Symbols of Soviet defiance raised on the grounds of the former camp.

These workers were amongst the only Jews to ever set foot in the Salaspils camp. Unlike the Reich’s concentration camps, which answered to their own central administration in Berlin, the Police Prison Camp at Salaspils was under the direct control of local Security Police Commander Rudolf Lange. Its inmates were political prisoners and Baltic dissidents, expanding in summer 1942 to provide ‘labour correction’ to those caught avoiding work regulations; and from 1943 the camp began taking in Baltic police officers and military personnel convicted in SS courts. The Salaspils camp also operated as an intermediary transit camp for prisoners being transported from Belarus and Russia, to forced labour projects in Germany. A large number of children were imprisoned at the camp too, allegedly in dedicated children’s barracks.

Flowers left in memory of the camp’s victims.

By the later part of 1942 the camp consisted of 15 barracks that between them housed 1,800 prisoners. By summer 1943, there were 30 barracks. Prisoners here were involved in the digging and processing of peat, and according to survivors’ accounts, regardless of its specific ‘Police Prison’ designation, the organisation of work, and treatment of prisoners at Salaspils, was just as brutal as any of the other Nazi camps in the region.

From left to right: Solidarity, The Oath and Red Front.

The official website for the Salaspils Memorial states that, during its years of operation, roughly 23,000 people were imprisoned at the camp. It reports that from May 1942 until September 1944, up to 500 prisoners died of diseases, as many as 150 from exhaustion or brutal punishment regimes, and a further 30 were shot while attempting to escape. The younger prisoners were particularly susceptible to the diseases (such as measles and typhoid fever) that ran rife through the inmate population. It is believed that half the camp’s children died from illness, and after liberation, a mass grave was discovered containing the corpses of 632 children aged 5-9 years old. The Salaspils website suggests that, including the Jewish forced labourers who died during construction, the final death toll of the Salaspils camp stood at more than 3,000 people.

Left: The Unbroken; right: The Mother.

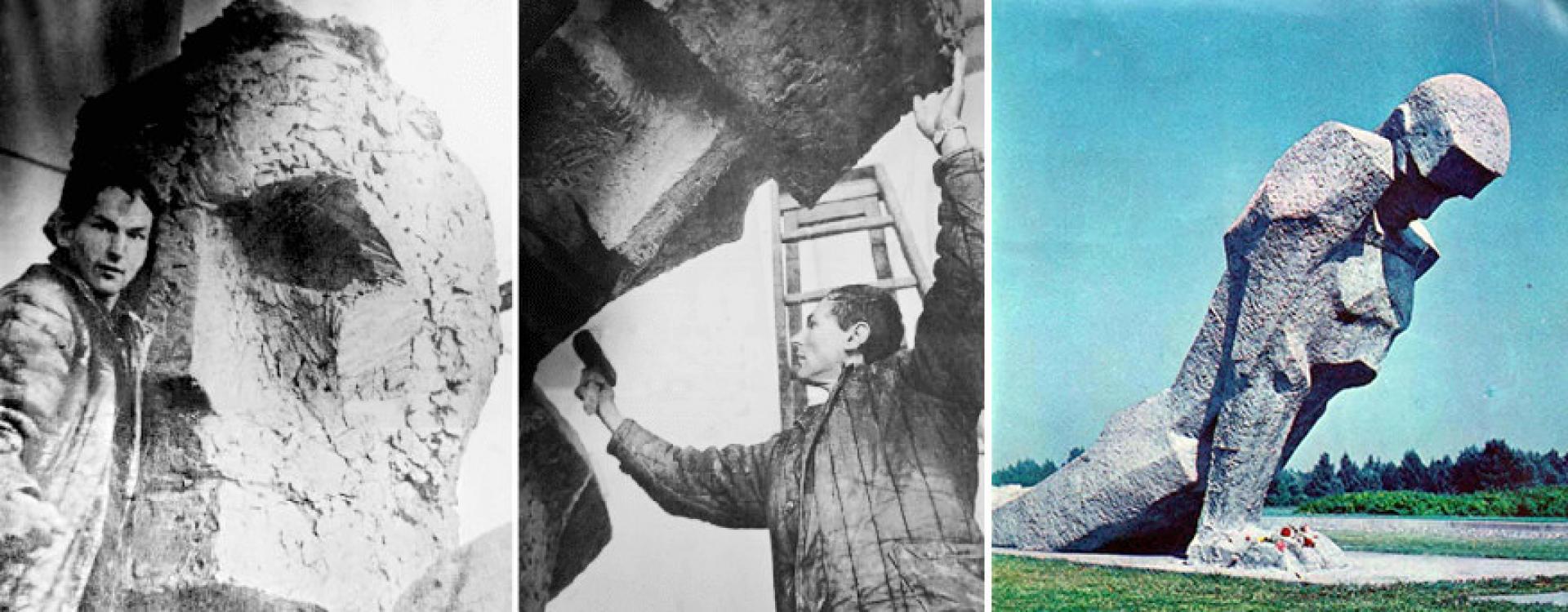

The Salaspils camp was liberated by the Soviets in September 1944. The fences were brought down, the barracks destroyed, but it wasn’t until two decades later that they constructed a grand memorial complex on the site where the camp once stood. A competition was held to select a design for the Salaspils Memorial Ensemble, as it was known, with the winning entry submitted by a team of seven: the architects Gunārs Asaris (who would also create the Monument to the Sailors and Fishermen Lost at Sea, at Liepāja), Oļģerts Ostenbergs, Ivars Strautmanis and Oļegs Zakamennijs, along with the sculptors Levs Bukovskis, Oļegs Skarainis and Jānis Zariņš. The park opened in 1967, and in 1970 its creators would receive the prestigious Lenin Award for their work – in the same ceremony that saw architect Yevgeny Vuchetich awarded for his famous monument at Volgograd: The Motherland Calls.

The opening ceremony was a grand, flower-laden affair, and the Salaspils Memorial Ensemble would go on to be considered one of the most important Soviet memorial sites in the Baltics.

The sculpture called Humiliated.

Today it is not a particularly easy place to visit, and emerging from the trees into the clearing is a sobering moment. The simplicity of these concrete forms invites imagination. Instead of telling you what happened here, this place tries to make you feel it. I found myself reminded of my visit to Auschwitz – a visit I made on a warm summer’s day, birds singing, woodland flowers in bloom. If anything the setting for Salaspils was even more picturesque than that, and I felt a sense of emotional whiplash, after a while, constantly trying to square what I knew about this place with the information my senses were providing me.

The ensemble is built around nine concrete titans (in six installations), who tower over the neat lawns and were said to represent the different types of prisoner kept in the camp. ‘The Unbroken’ lies on his belly, pushing himself up with his last strength. ‘The Mother’ has a look of defiance, standing square to shield the infants that cower by her side. ‘The Humiliated’ kneels, her face partially hidden by an arm raised in a defensive gesture. In the very centre of the lawn, three forms are arranged side-by-side: ‘Solidarity’ shows one prisoner helping another to stand; ‘The Oath’ is a man stood tall stretching his arms into the air; while ‘Red Front’ likely represents a fighter from the paramilitary wing of the German Communist Party – the ‘Rotfrontkämpferbund’ – a group who used the same single-handed fist salute depicted here.

A memorial block where the camp’s gallows once stood.

The Salaspils Memorial features hardly a written word of information but that does not make it a quick place to visit. The monuments that decorate the lawn demand consideration. A single notable script appears on a stone block placed off to the right, between the central figures and the entry gate, marking the location of the former camp gallows. Its inscription in Russian and Latvian reads: “Here humans were executed for being innocent… Here humans were executed for every one of them being a human and loving the Motherland.”

Fragments of the original barrack walls.

At the opposite side of the Road of Death – as the designers named the walking path that circles their concrete giants – a black granite pedestal is designated as the place for laying flowers and memorial wreaths. From somewhere out of sight comes the ticking of a metronome. Intended to suggest life, and the eternal passage of time, the sound is rather like a heartbeat, and lends an uncanny atmosphere to my time amongst the statues.

The old camp buildings may be gone, but here and there, fragments of the outermost walls remain. Some are bare, but others are piled with tributes: plastic angels, Orthodox icons, a selection of sad-looking children’s toys. It feels like an effective memorialisation technique – bulldozing the camp, symbolically destroying its physical legacy, while leaving just enough of its form behind to suggest a historical record of its size and inner geography. Just a year before the Salaspils Memorial opened, the Yugoslav architect Bogdan Bogdanović had accomplished something similar at his Jasenovac Memorial Site, in what is now Croatia: the buildings of the old concentration camp were destroyed, but there, the ground was landscaped into mounds and craters that recorded the location and function of the various different buildings.

Text across the wall of the gallery “Beyond these gates the land groans.”

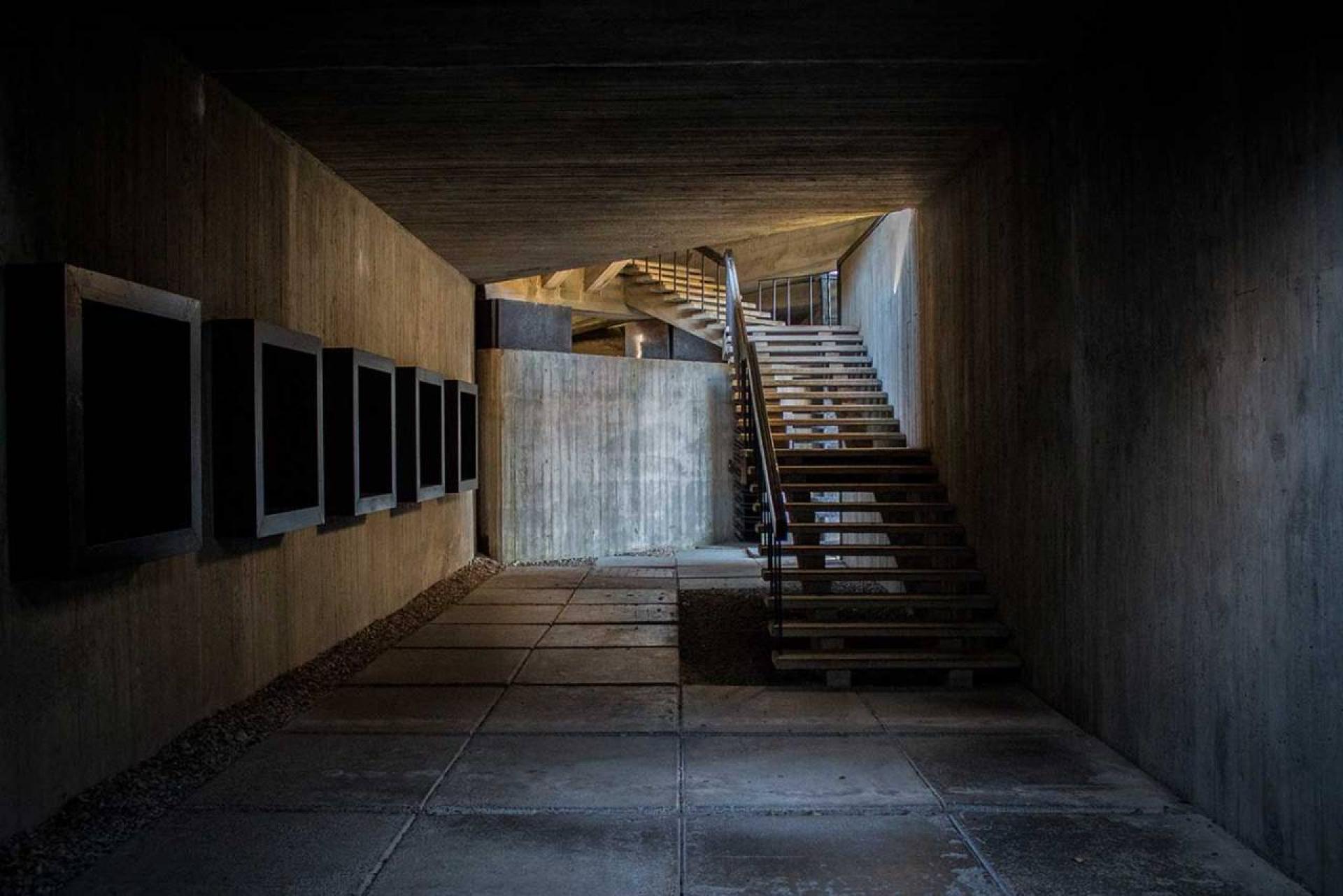

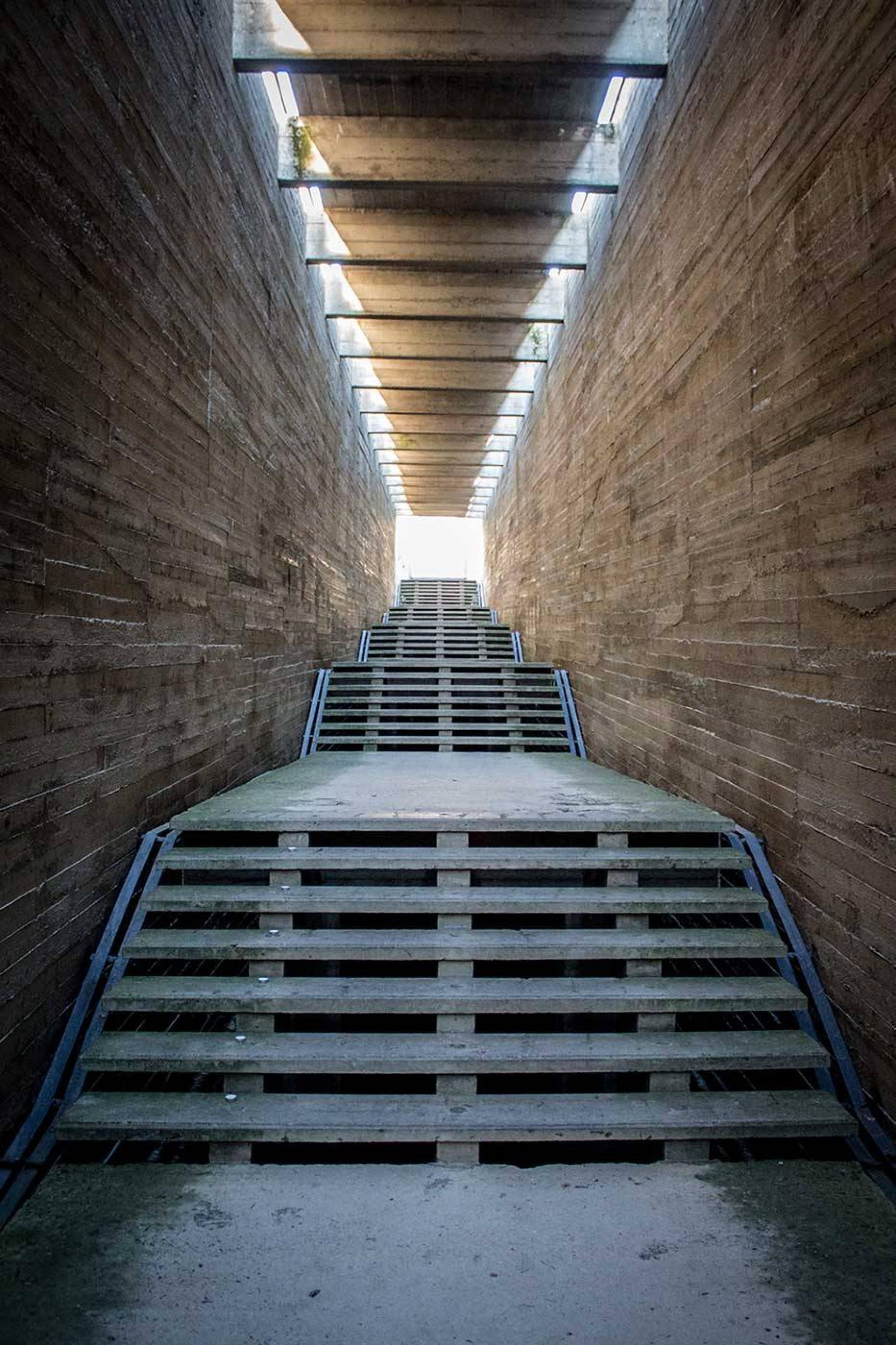

The only building at Salaspils now is the gallery – entered by an inclined walkway that passes through the length of the imposing concrete arch above the entrance. The space inside is oppressive and claustrophobic, presumably by design. This effect of sensory deprivation allows the visitor time to meditate, perhaps, and process the meaning of the monumental forms outside. When natural light does break through the side walls, it spills in at viewing slots reminiscent of wartime pillboxes. I peer outside, for a panoramic view of the figures on the lawn.

All the while, the sounds of the forest seem amplified as they reverberate though this enclosed space. There is birdsong, the noise of distant dogs barking, and somewhere nearby, where the original tracks cut lines through the trees, the shunting and hissing of cargo trains.

The walkway through the Brutalist gallery building.

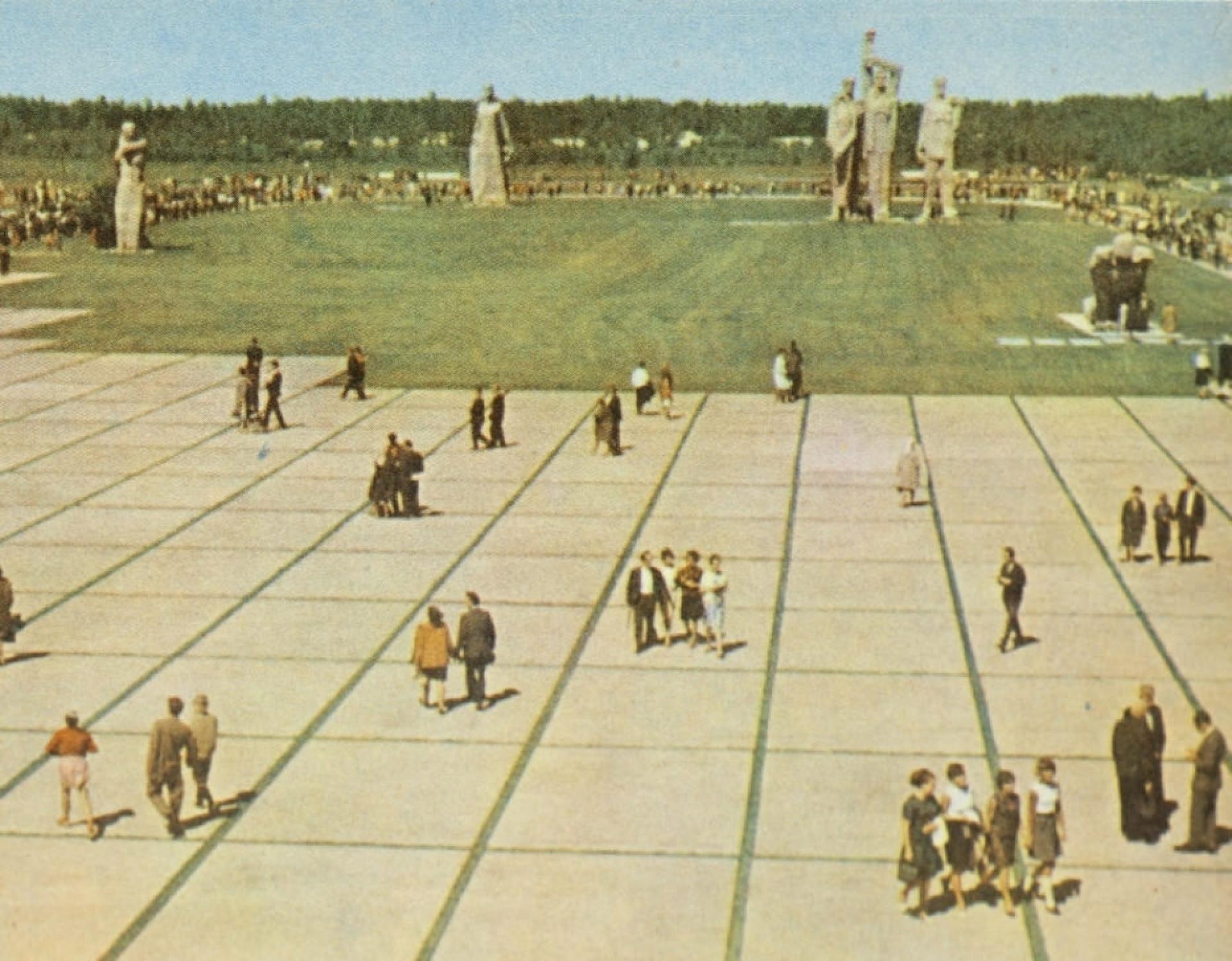

The Salaspils Memorial Ensemble, seen from the gallery.

There is something inherently totalitarian about the form of remembrance prescribed by the Salaspils park. The sheer concrete, the lack of information. These twisted human figures tell visitors how they should feel, but the park never provided the tools for a two-way conversation. At Auschwitz visitors are shown piles of shoes, and suitcases, visual triggers designed to encourage an engagement with the numbers. At the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide in Kyiv, Ukraine, a similar effect was achieved with grains of corn – arranged in a heaped display where one grain stands for one Ukrainian life lost. Salaspils, in contrast, simply says: these people were punished for loving the Motherland.

Commenting on the Soviet Union’s choice to memorialise Salaspils, Peter Hohenhaus notes how “other, even worse sites of the Holocaust such as Biķernieki received no commemoration at all.” It is perhaps no coincidence though, that the Soviets chose to create such a prestigious memorial over the remains of a camp which had less relation than most to the Jewish Holocaust. (Aside from the construction team, it is reported there were only 12 Jewish prisoners at Salaspils).

Following the war, the Soviet Union severely downplayed the significance of the Holocaust, to present the Soviet citizen, instead, as the chief target of Nazi aggression. Any specific commemoration of the Jewish tragedy was at least discouraged. For example there was a Holocaust memorial built in Minsk, Belarus, named ‘the Pit’; an obelisk on the site where 5,000 prisoners from the nearby Minsk Ghetto were executed by fascists in 1942. Its creators, the stonemason Morduch Sprishen and the poet Haim Maltinsky (who wrote the Yiddish inscription), were both later convicted on charges of Jewish nationalism, and after that, the authorities treated all visitors to the Pit memorial with suspicion. At Babyn Yar meanwhile, a ravine in Kyiv were tens of thousands of Jews were massacred, the victims of the Holocaust are still yet to be recognised with a proper memorial.

The USSR’s post-WWII efforts to ideologically bond its member republics through a shared sense of victimhood, and victory, was felt not least strongly in places like the Baltics – countries who were new Soviet subjects, and uneasy subjects at best. What better place then, for a grand Soviet memorial park, than Salaspils: a police camp that had chiefly housed antifascist Baltic dissidents, and Soviet citizens from Russia and Belarus. It was a place where Latvians and Russians had suffered together, side by side, and of all the dark places left to this region in the wake of Nazi occupation, this was the one whose memorialisation best supported the post-war political narratives of the Soviet Union.

The Salaspils Memorial is recognised as part of the Latvian Culture Canon and in 2017, it was declared a monument of national significance. Despite this recognition however, it doesn’t feel like a place that is cherished, so much as observed. Visitors often report having trouble locating the place, and it hardly seems to be promoted as a tourist destination of note. When compared to videos showing the park’s opening ceremony (crowds of people, neatly trimmed lawns, and the forest pruned back around them), Salaspils today appears somewhat lonely and dishevelled.

Contemporary additions and modifications to the park have seemingly challenged the innate Sovietness of the place. A cemetery for German POWs was added in 2008, adjacent to the main memorial grounds. More recent is the installation of the Salaspils Memorial Exposition. Housed inside the Brutalist gallery building, the collection has been open to visitors since February 2018, and features information and video clips available in Latvian, German, English and Russian.

Tributes left by visitors to the Salaspils Memorial.

Elsewhere around the park, and dotted along the ‘Road of Death,’ new information panels have been installed to give context to the park’s otherwise sparse concrete symbolism. The memorial architecture of the park tells the story of Soviet people who fell victim to the Nazis. It is somewhat jarring then, to read contemporary panels that describe both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union as “occupying regimes.” This is, of course, how the Latvians officially remember that portion of their history: as a violent occupation by a foreign power that would maintain a political and cultural stranglehold over Latvia for the next 45 years. If it seems strange to foreign visitors that a site as significant as this – and so close to the capital – should feel quiet, hidden away, and poorly advertised, then perhaps this is why: from a Latvian perspective, the Salaspils Memorial might very well feel like a monument built by one trespasser to present themselves as the chief victim of the previous one.

The main gallery space inside the visitors’ building. Below: the staircase inside the inclined viewing gallery.

According to the website, the new exhibition “provides visitors with information based on historical facts and the conclusions of the latest scientific studies,” in an effort to “dispel misconceptions about the Camp and the Memorial.”

Those “misconceptions” presumably include certain claims made in the Russian-language media. Many on that side of the border still believe the former Soviet account, which once stated that over 100,000 people had died at Salaspils (compared to the 3,000 cited today by the Latvians). There were stories, too, that the Nazis drained blood from children here to use in transfusions for German soldiers – though these seem to have since been largely debunked. Nevertheless, news outlets like RuBaltic.ru and Ukraina.ru accuse the park’s Latvian management of downplaying the numbers, rewriting history, and more generally of presenting the Nazi presence in Latvia as having been less harmful than that of the Soviets who liberated this camp. They refer to a new information panel at the Salaspils Memorial, which shows respective death tolls for the periods of Nazi and Soviet occupation; the Soviet number being the larger of the two.

While obviously Latvia can and should be having these conversations, I can’t help but wonder if it isn’t slightly antagonistic (at least, to the ethnic Russians who make up a quarter of Latvia’s population), to have them here; to stand on the symbolic graves of dead Soviets while comparing them to the Nazis.

‘The Humiliated’ is partially hidden now, behind a tree not part of the original design for the memorial.

Memorials should serve a simple task, in theory: they remind us of things that we must not forget. They preserve important stories for those who were not there, and in societal terms, they serve to reclaim – to re-consecrate – ground once bloodied by violence. Danger zones become places of (re)education. But the invisible memory wars that continue to be waged across this quiet lawn in Latvia are anything but simple, and they hint at some of the greater cultural conflicts at large today in the post-Soviet Baltic states.

The last thing I saw before I left was another new, post-Soviet addition to the park. In 2004, a former prisoner at Salaspils named Larry Pik funded the creation of a new monument to the Jewish victims of the camp – the prisoners who built it. Accompanied by the Star of David, an inscription in Hebrew, German and Latvian reads: “To honour the dead and as a warning to the living. In memory of the Jews deported from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia, who from December 1941 to June 1942 died from hunger, cold and inhumanity and have found eternal rest in the Salaspils forest.”

The cover of a 1969 commemorative book about Salaspils.

Left: a newspaper announces the Lenin Award given to the Salaspils design team. Right: ‘The Mother’ under construction.

‘The Unbroken,’ under construction, and then completed.

The gate to the Salaspils Memorial (late 1960s).

Visitors queue to enter (late 1960s).

The memorial plaza at Salaspils (1968).

Left: Salaspils in 1975. Right: Cover of the 1985 Salaspils brochure.

The Salaspils Memorial Ensemble in 1970.

by Darmon Richter

[adapted with permission from an article at Ex Utopia]