FOMA 44: Forgotten Sarajevo

During our online conversation Lejla texted me that it is difficult to come across reference material in Bosnia in general as libraries and archives have been burnt down and there hasn’t been enough digitisation.

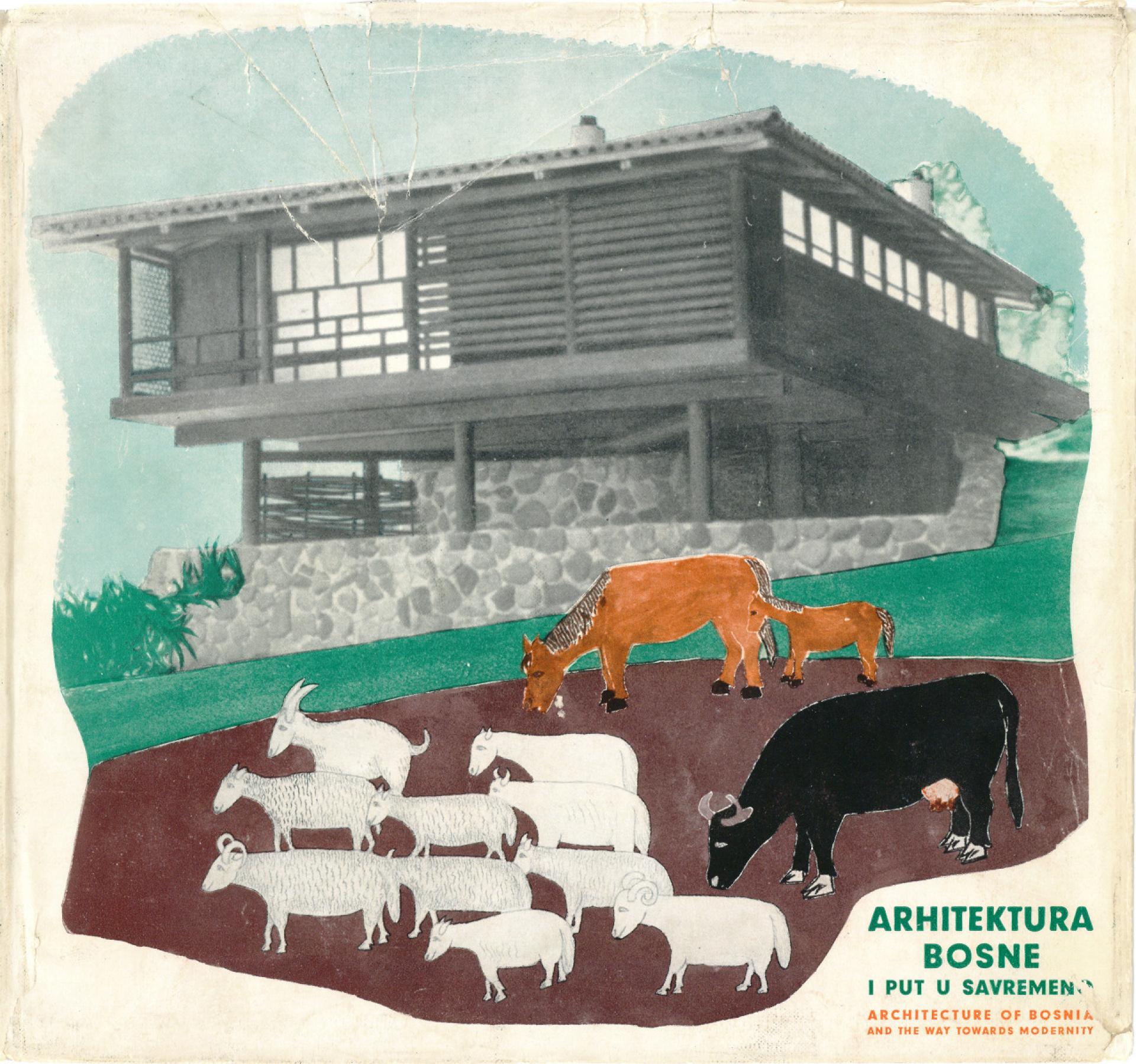

Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity by Dušan Grabrijan and Juraj Neidhard, Sarajevo 1957

The 1984 Winter Olympics known as Sarajevo ‘84, was held between 8 and 19 February 1984 in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia.

Let’s have a look of five impressive Forgotten Masterpieces in Sarajevo. Designed by Živorad Janković and Halid Muhasilović, Skenderija is a multi-functional cultural and sports centre completed in 1969. This building was the first of its kind in the former Yugoslavia and in many ways acted as a prototype for many similar complexes that were later built throughout the country. As such, Skenderija played a curial role in the development of not only the local architecture, but also of Yugoslavian modernist architecture as a whole. It was the first hybrid building in the former Yugoslavia that fused together many different functions (sports, performance, entertainment, shopping, food, service, etc.) within a singular multi-storey complex that employed a modernist aesthetics prevalent of the time.

The complex consists of three buildings; a large sports hall in the first, a number of smaller sports halls in the second building and Dom Mladi (House of Youth) with cultural content in the third. | Photo Lejla Odobašić Novo

The buildings are arranged around an open plateau, a city agora, under which is located a subterranean commercial level with a circulation path that allows access all three buildings. The project was innovative in the complex construction system used that allowed for large spans. It also reflected the modernist ambition of honesty in the material use, with the concrete articulation of all the façades. In many ways, due to its scale and cultural significance, the complex shifted the symbolic gravitation from the old city centre and established an additional point of prominence. In urbanistic terms it expended the city beyond the exiting east-west axis and opened the south bank of the river Miljacka.

Skenderija allowed Sarajevo to take on a new cultural significance that would later be sealed by the Winter Olympics in 1984. | Photo Lejla Odobašić Novo

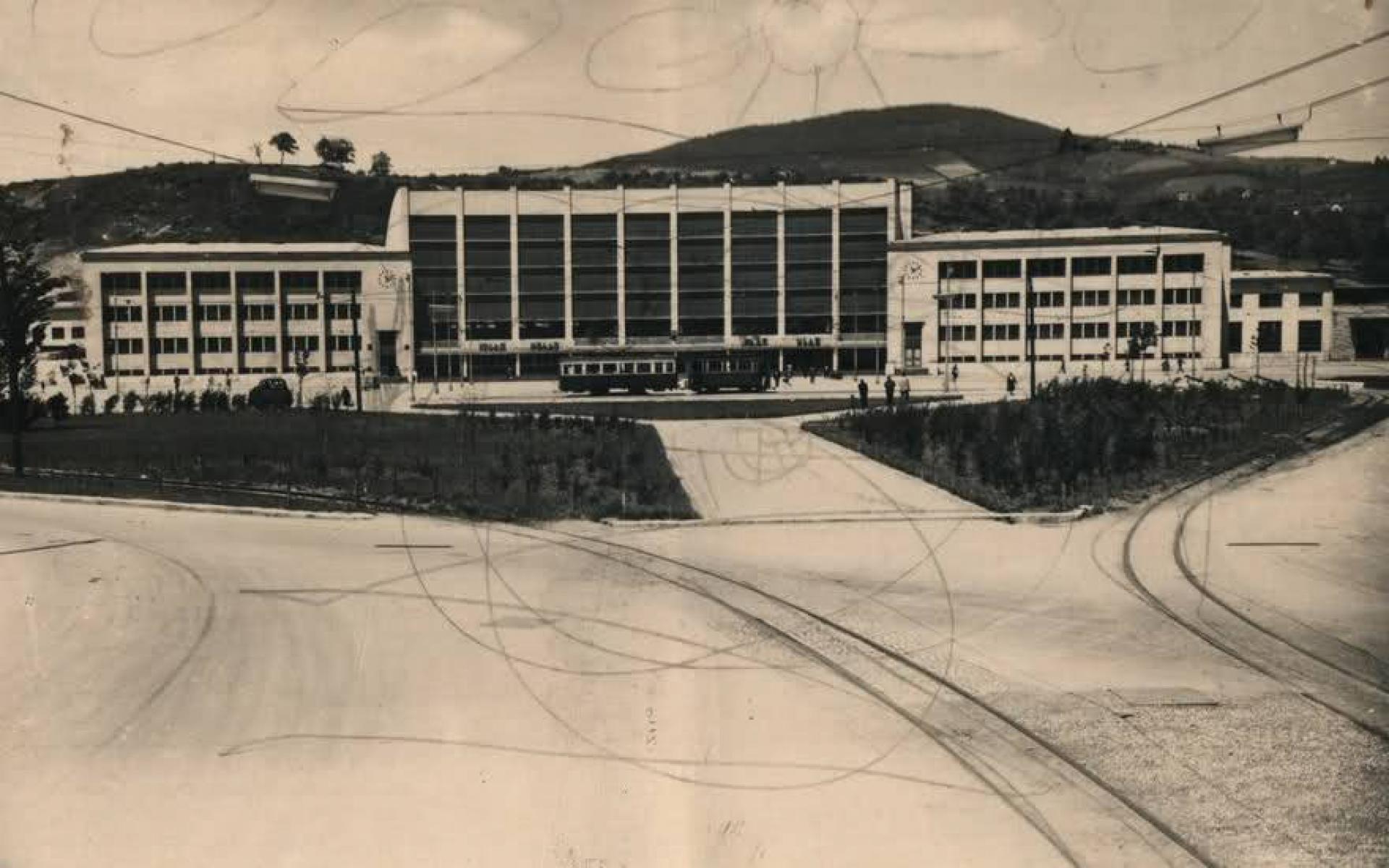

The Communist Party of Yugoslavia started the project of the Sarajevo’s main railway station as an architectural competition with the ultimate goal of physically uniting the country through its railway system. At the beginning of Socialist Yugoslavia, the country’s political views strongly aligned with those of the USSR and the remainder of the communist bloc. As such, Yugoslavian architecture at this time, although modernist in spirit was still heavily influenced by the social realism that was used as a political tool and prevailed in the majority of the eastern bloc countries.

The Railway station was opened in 1952 and in its thirty years of function, up until the siege in 1992, the building was one of the most monumental structures in Sarajevo. | Photo via Mirza Hasanefendic

Social realism in Sarajevo brought on a range of contradictions in its architectural articulation. It ranged from architecture for the masses most clearly articulated in the residential settlements for the worker’s housing to that of highly articulated and relatively well executed public buildings, mostly designed through architectural competitions.

The main railway station in Sarajevo reflects the complexity of a more western modernism. | Photo Lejla Odobašić Novo

Once the initial reconstruction phase after WWII was completed cultural and institutional buildings became the next phase of focus. One of these included the Ministry of Public Health. It is heavily modernist in nature, however, the social realist influence remains visible. It was built only a few years after the main railway station but the break away from the social realism is even more apparent in this case. This shift in architectural expression occurred as a direct result in the political and ideological drift between Yugoslavia and USSR.

The building relies on pure geometry, abstracted decoration in the form of vertical fins at the front façade, simplified openings and a receded top floor which allow for a terrace on the top floor. | Photo Lejla Odobašić Novo

The principal focus of the social realism buildings was an exaggerated scale in order to instill the notion of grandness of the state and to inspire deference towards the authorities, which in this case was the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. Since this building was designed and built as a Ministry of Public Heath, Ivanović strived to employ majority of these principles but he broke away from some keys aspect that defied socialist realism at the time.

The building follows the rigid symmetry often employed by social realism and breaks a number of rules, which shift it towards a more ‘western’ modernist building. | Photo Lejla Odobašić Novo

The Communist party took control of Yugoslavia following the end of WWII in 1945. Like the majority of European cities, a considerable damage was suffered by the urban fabric in Yugoslavia as well. As such, one of the major tasks of the new socialist system was to rebuild as fast and as efficiently as possible. However, both the amount of resources and the number of available architects was limited and as such the initial wave of reconstruction was very utilitarian.

One of the most notable residential projects that dates back to the post-war period is the residential complex on Džidžikovac that resulted from a design competition set forth in 1947 and won by the above-mentioned Kadić brothers. The project was completed in just over a year which resulted in relatively poor construction quality, which was the case with many residential buildings constructed around this timeframe.

The design and the modernist spirit of the project render it as one of the most notable residential complexes in Sarajevo. | Photo Lejla Odobašić Novo

The complex contains three linear residential blocks each consisting of a number of three-storey interconnecting buildings that cascade along the existing topography. In addition, the three blocks are surrounded by open green space that integrates the building into the existing site forming a sense of a unified complex. Although the project has been declared as a protected national monument in 2008, the reconstruction done since the end of the siege in the 1995, has been to a large extent insensitive to the initial design principles of the Kadić brothers.

Each block have a set of semi-circular terraces suspended by receded columns - the signature feature of this project. | Photo Lejla Odobašić Novo

Completed in 1956, six years after the Ministry of Public Health, Residential Building and Šipad Headquarters breaks away from the social realist influence and draws inspiration from Oscar Niemeyer instead, thus creating one of the most prominent modernist buildings in Sarajevo.

Although the two buildings are separate entities they lean on each other and share a part of the side wall. | Photo Lejla Odobašić Novo

In order to allow for a continuous pedestrian flow, Ivanović frees part of the ground floor of the Šipad Headquarters, and thus creates a covered promenade lined with the distinct V shaped columns visually suspending the building off them. | Photo Lejla Odobašić Novo

Lejla Odobasic Novo is a Bosnian-Canadian architect and an architectural theorist who is currently working between Sarajevo and Toronto. She obtained her bachelor and master’s degrees from the University of Waterloo School of Architecture where she also held a research position and upon graduation worked as an Adjunct Professor at the Rome Campus. She holds a professional licence issued by the Ontario Association of Architects (2014) and is an Assistant Professor at the International Burch University in Sarajevo where she obtained her PhD and currently teaches architectural design and architectural theory. Lejla’s research focuses on the role of architecture, and in particular cultural heritage, in conflicted and contentious places. Within this field, she has carried out projects, exhibitions, publications and other cultural initiatives including her work with Liana Breser, Jerusalem-Sarajevo: In-between Cities, that was exhibited in Canada, UK, Bosnia and Croatia (2010-2011). She has also participated in DAAR Decolonizing Architecture residency and research group in the Palestine under Eyal Weizman, Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti (2010). Lejla is also a member of Kuma International, an International Center for the Visual Arts from Post-Conflict Societies. In addition to her academic work, she has also worked in architectural practices internationally including Toronto, London, Madrid, Rome and Istanbul.