FOMA 30: 100 British Churches

British churches of the 20th century have suffered from a lack of recognition, which can partly be attributed to the increasing secularization of the era and a wider problem of interpretation. In the UK, the idea of a historic church is firmly rooted in the Medieval, and tends not to be associated with the architectural tradition of the last 100 years.

The book 100 Churches 100 Years, written by the 20th Century Society (Published by Batsford, edited by Susannah Charlton, Elain Harwood and Clare Price) acts as a corrective to such assumptions, celebrating the church architecture of Britain from 1914 onwards. As it demonstrates, these buildings have tended to be more informal than the churches of earlier eras.

Innovative technology and materials like concrete and steel enabled a freedom to express new ideas about how congregations could participate, changing layouts and emphasizing inclusivity. With ambitious engineering and space for new decorative forms - including stained glass, murals and sculpture – they provide an inventory of the ecclesiastical crafts as well as insights into new ways of bringing people together in shared worship.

Some are intact; others less so, and collectively they suffer from a wider lack of appropriate conservation skills. The 20th Century Society believes that it is time to redouble the conservation effort for this highly rich era of church architecture.

St Leonard’s Church is located in St. Leonards-on-Sea in East Sussex (1961). | Photo © Elain Harwood

The Grade II listed St Leonard’s Church is a rare collaboration by the brothers Giles and Adrian Gilbert Scott and replaced a 19th century Gothic chapel that was bombed in WWII. Built into the cliff behind, it is currently closed, because of fears of structural instability. This means that its interior is hidden, which is unfortunate, as it contains stunning Patrick Reyntiens glasswork and has a charming maritime theme, with the pulpit made from the protruding prow of a fishing boat imported from Galilee and the lectern a reused binnacle or ship’s compass. The blue-grey Hornton stone around the walls carries a wave motif, and it has inlaid fish on the chancel floor.

St Andrew, Livingston, Scotland (1969-70). | Photo © John East

Built as a Catholic place of worship for the new town of Livingston, St Andrew’s was designed by George Kennedy of Alison and Hutchison and Partners, a notable Scottish Modernist practice. Its dramatic exterior is marked by curved walls of board-marked concrete, with one of the curves thrusting skyward in a simulacrum of a spire. Essentially circular in plan, the top-lit interior is more delicate that the concrete exterior suggests, with curved white walls and a boarded timber ceiling. Although it has been altered, it retains much of its original character.

Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, Liverpool (1967). | Photo © John East

Perhaps the best known of all post-war British churches, Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral rises from Hope Street in a powerful composition of abstracted forms and intersecting geometries, while within is a showcase of post-war art and design. Frederick Gibberd’s building shows its bare bones – 16 immense ribs being the primary structural component inside and out – and constitutes a cathedral fully in the round, made to bring the clergy and the laity closer together, with its central Sanctuary top-lit by the largest continuous, Dalle-de-verre window in the world. A mascot and homecoming beacon for Liverpudlians.

St Oswald, Tile Hill, Coventry (1956-7). | Photo © John East

One of three suburban churches commissioned by the Bishop of Coventry from Basil Spence, the Grade II listed building was driven by Spence’s promise to provide a ‘simple, direct, topical and traditional solution’ for local congregations. Costs were reduced by using the same construction firm and material as those employed for nearby housing. Funding came from the War Damages Commission in compensation for one destroyed inner-city church.

The basilican form of St. Oswald was derived from that of the Cathedral (then under construction), with a concrete portal frame giving dignity and rhythm to the rugged interior. Like its sister churches, St Oswald has extensive glazing, a patterned ceiling, lettering by Ralph Beyer, and robust chancel furniture. An appliqué hanging was made by Gerald Holtom for the altar wall and a beaten copper sculpture by Carrol Sims for the east gable. A low-slung hall at right angles (rebuilt in 2000) and openwork concrete tower define the boundary of a garden enclosure.

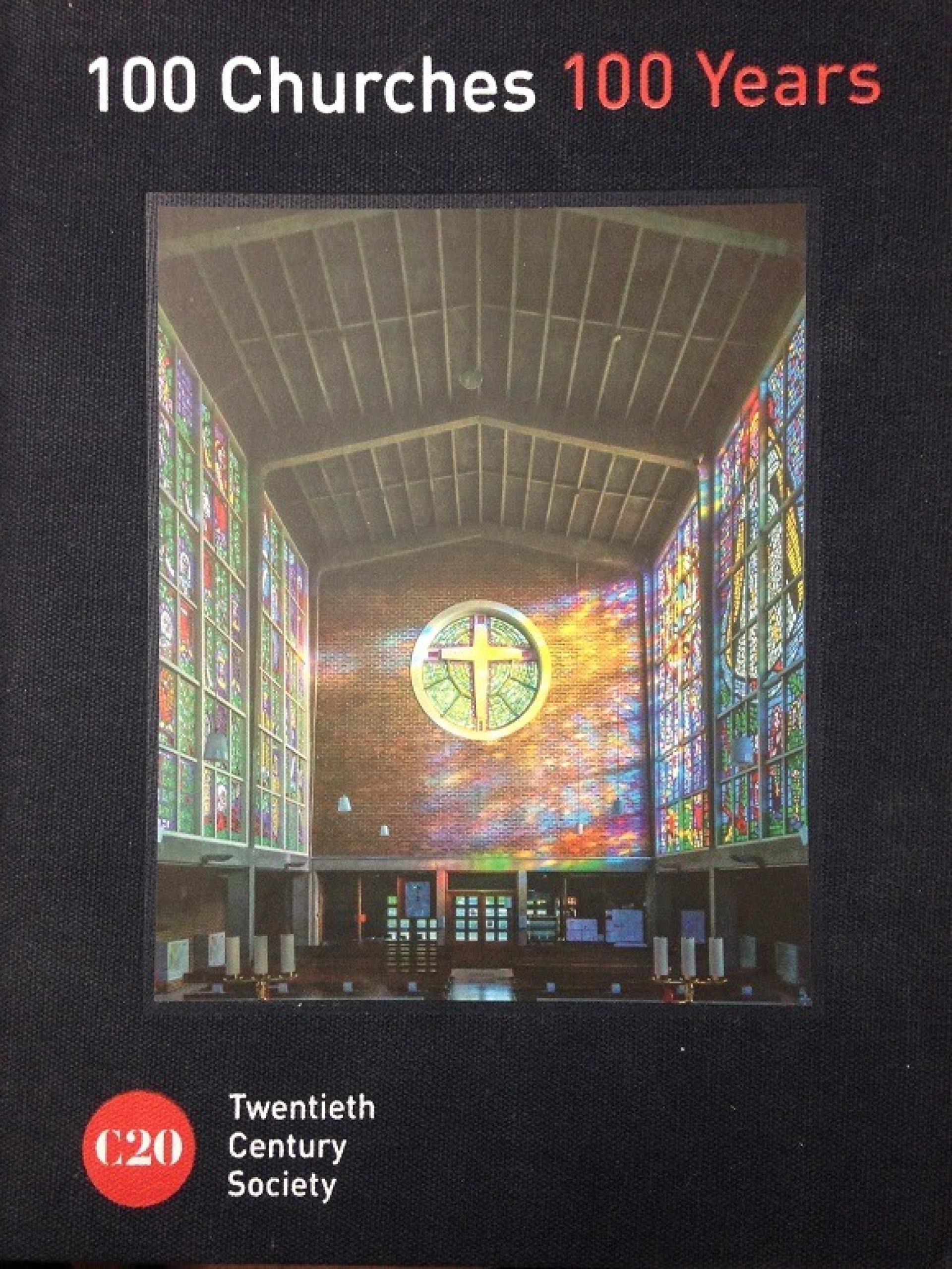

Our Lady of Fatima, Harlow, Essex (1960). | Photo © John East

Gerard Goalen’s Our Lady of Fatima church at Harlow is a classic statement of mid-century aesthetics. It has a spare reinforced concrete frame, following the examples of Continental work by Auguste Perret and Rudolf Schwarz, allowing great expanses of stained glass (by Charles Norris) and plain brickwork. The low-pitched, exposed concrete roof beams and purlins are rather utilitarian but its T- shaped plan is a clear and straightforward expression of the liturgical reform principles that sought to put the Mass centre-stage, enveloped by the congregation.

Clare Price is the head of casework at the C20 Society and has worked for the Society since 2012. She is responsible for the Society’s church casework across the UK and secular buildings in the north and west London boroughs. She is currently researching for a DPhil at the University of Oxford, with a particular focus on interwar church architecture. With an MSc in Conservation of the Historic Environment, Clare is also a qualified chartered surveyor who has worked in commercial property and building conservation for over 20 years.