FOMA 26: UK Post War Experiments

Ross Nesbitt has chosen post war Forgotten Masterpieces in the UK according to their influence, innovation, but above all how they have interacted with the people using them.

Scottish Secretary Willie Ross and his wife at the opening of the Red Road flats in Glasgow (1964). | Photo via Read Road Pinterest

Each building illustrates how the response of the Modern Movement to the challenges of reconstruction and planning in post-WW2 era Britain touched on many aspects of daily life: religion, education, retail, work and transport. And they all divide public opinion.

Starting with the original medieval Coventry Cathedral, destroyed by the Luftwaffe on 14 November 1940 in an air raid code-named Moonlight Sonata.

Rebuilding of the cathedral started in 1955, and by the time of the consecration it had become a symbol of hope and reconciliation. | Photo by Ross Nisbet

The attack targeted Coventry’s industry, but it was clear that collateral damage and casualties would be considerable. The city was hit by 200 bombs and among many buildings also the cathedral fell. Only the tower, spire and outer wall survived.

Sir Basil Spence was the only architect to insist that the ruins of the old cathedral should remain intact. | Photo via The Twentieth Century Society

The morning after Provost Richard Howard wrote in chalk on the sanctuary walls “Father, Forgive.” On Christmas 1940 the BBC Home Service broadcast Howard’s message from the cathedral ruins. Howard’s gesture of forgiveness inspired Spence, which was chosen from over 200 architects in a competition in 1951 to design a new cathedral.

From Priory Street we find Sir Jacob Epstein’s large sculpture of Archangel Michael triumphing over the Devil. | Photo by Ross Nesbitt

The main body of the new cathedral is built from red Hollington sandstone, in unity with the ruins of the old. A high porch links them. Zigzag walls with angled windows direct light down the nave onto the altar. The floor is of polished fossil stone. Large artworks commissioned by Spence include stunning abstract stained glass windows by John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens and a tapestry behind the main altar by Graham Sutherland, thought to be the largest in the world.

The Charred Cross emphasize the reconciliation theme. | Photo by Ross Nesbitt

After the bombing, cathedral stonemason Jock Forbes noticed two burned wooden roof beams had fallen in the shape of a cross. He tied them together, forming an altar which Spence preserved on the stairs between the new and old part of the cathedral. Provost Howard took three nails from the smouldering beams to make the Cross of Nails, which became the centerpiece of the altar cross in Spence’s new cathedral.

Spence’s design draws effectively from the cathedral’s history and post-war mission. It’s an uncompromisingly modern construction but also perfectly integrated with its past. Coventry Cathedral shows the visitor the waste and loss of war without flinching, but is not a forbidding structure. Wood is used to great decorative and functional effect, giving warmth and human scale to the nave and choir. The Gethsemane chapel highlights Spence’s talent for juxtaposition and interaction: the visitor passes Spence’s harrowing crown of thorns icon to enter a warm sanctuary beneath war artist Steven Sykes’ dazzling angel mosaic in gold leaf and blue tile.

The Roger Stevens Lecture Theatre is the centerpiece of the complex of buildings for the Leeds University campus. | Photo by Ross Nesbitt

Britain saw a great expansion in education as the post-war generation grew up. The number of students and universities nearly doubled from 1960s to 1970s. Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, who had just completed the acclaimed Golden Lane Estate, were engaged as Master Planners at the University of Leeds to oversee in-house architect Geoffrey Wilson and provide expertise to the expansion of the campus. They produced a plan in two phases. An initial report recorded their enquiries and research into the existing campus and set out their vision for the new campus. It summarized the anticipated problems and posed solutions, specifying the required materials, time, space and costs. A second Development Plan focused on the maths and science precinct and features the Roger Stevens Lecture Theatre.

The design was a forward-looking city within a city, and in many ways an important trial run for the Barbican estate. The Development Plans saw Chamberlin, Powell and Bon experimenting with ideas about the principles of urban design, the integration of community and environment into a cohesive whole, and the most economic and adaptable use of space. The plans generated interest at an international level and were influential to the modern movement as a body of research and a definitive model for the modern university campus.

The building’s unconventional configuration of space does require a bit of thought to learn its signage and color coding. | Photo by Ross Nesbitt

The building contains 25 tiered lecture theaters with different capacities, a refectory and reprographics facilities. The exterior is futuristic and striking, compared to a church organ, robot or car engine by students. The refectory overlooks a lake, which is more than ornamental as it was designed to provide air conditioning for the building, same idea architects developed on a bigger scale with the Barbican Lake. The layout is deceptively simple, two gently sloping staircases link the lecture theaters and each row of seats has its own individual door, ensuring lectures are not interrupted by latecomers. Its listed status ensures the Roger Stevens Lecture Theatre’s future is safe. It’s another divisive building but maybe it’s just waiting for the rest of us to catch up with it.

An early example of pedestrian planning, Castle Market was a multi-level complex that made maximum use of a compact site. | Photo by Ross Nesbitt

Castle Market built in stages between 1959 and 1965 was named after Sheffield Castle. It was almost entirely demolished in 1648 but the remains of the foundations are visible beneath the market. Like Park Hill and Gleadless Valley, Castle Market was a thoughtful and rewarding design, which made great use of Sheffield’s famous hills and valleys. Womersley and Darbyshire recognised what made Sheffield an interesting place to build was its slopes and dips, and created a complex with soaring heights (the walkways and Rooftop Cafes) and three labyrinthine floors of markets below, all with access to the street on different levels of the Castle Hill.

Inside, Castle Market was closer to a modernist re-imagining of Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar than the blandly interchangeable malls of today. It was a treasury of mid-century modern mosaics, signage and tile designs, geometric and multi-coloured in seemingly endless variety. Layer upon layer of design eras cried out from every stall, competing for the shopper’s attention. Although postmodern signage was added to the walkways in the 1980s, most of Castle Market retained its original 1960s signage, including many classic “formica cafes” - one was used as a location in Shane Meadows’ “This is England ‘88”. The ascent to the Roof Top Café, with its sci-fi suspended ceiling and net curtains, offered stunning views of the city.

In Castle Market working class people bought groceries, met friends, drank tea and a gossipped. | Photo via English Cathedrals Archive

Pulp singer Jarvis Cocker had his first job there as a teenager, on John Firth’s fish stall. But not everyone appreciated Castle Market. Redevelopment had been planned as early as 1996 by Sheffield City Council, who wanted to expose the remains of the castle walls in a visitors’ centre. And of course, the surrounding area would be purged in the name of regeneration. This act of social cleansing did not go unopposed. An anonymous request for listed status for Castle Park was made in 2011. Sheffield’s Liberal Democrat City Council responded by trying to start a letter writing campaign in favour of demolition. English Heritage rejected the application: “In order to be considered for listing, 20th Century market halls should display a high degree of architectural, technological and historic interest. Those post-war market halls which have already been listed (such as Coventry) have particularly high levels of architectural innovation and artistic achievement which justify the designation of such late buildings.This is not shared by Castle Market in Sheffield."

Anyone familiar with both Coventry Market and Castle Market would agree that this comparison was patently false. Trading ceased in November 2013 and Castle Market was demolished in 2015. The markets were relocated to The Moor, on the opposite side of town. The new market is the kind of forgettable development that could have been built for any town in the UK.

The Spence’s project of a government office building in central London could not be more different to Coventry Cathedral. | Photo by Ross Nesbitt

After the Second World War, civil servants in London’s Whitehall were working in cramped offices built in the 19th century when government administration was smaller. With the post-war expansion of the British state, office space was needed outside the historic core of Whitehall. New offices on Queen Anne’s Gate were first planned in 1959, but the original plan of a more conventional tower block was rejected by the Royal Fine Art Commission. Planning permission for Spence’s revised design was given by the Westminster Planning Committee in 1969.

The building on 102 Petty France is in a sensitive location in central London: in view of Buckingham Palace, overlooking The Mall and two of the Royal Parks, St. James’s Park and Green Park. Historically, the site was previously occupied by Queen Anne’s Mansions, London’s first high-rise housing, built from 1873-1890. Today, Victorian properties are desirable and the mansion flat format is fashionable again, but the Victorian and Edwardian media decried mansion flats as Babylonian, factory-like and out of scale with historic Georgian buildings. Londoners feared for the value of their property if a sunlight-blocking mansion flat was built nearby. At 12 storeys high, Queen Victoria complained that the Mansions blocked her view. The Mansions tested the limits of planning law, prompting the introduction of height restrictions in the London Building Acts of 1890 and 1894. During WW2, the Mansions were requisitioned as Government offices and retained until they were demolished in 1973. Many in Whitehall hoped the site would be developed with a building more sensitive to the surroundings. What was proposed shocked them.

The 102 Petty France personifies the qualities people love and hate about Brutalism in equal measure. | Photo by Ross Nesbitt

Several Members of Parliament were outraged by Spence’s model and sketches. On 4 July 1972, Lord Reigate, speaking in the House of Lords, asked the Government to intervene and halt building. Calling Spence’s design a mass of monumental masonry, he went on to predict “this unlovely lump of a building will loom over London for a long time, and will, if I may say so, if it is allowed to happen, outlive all your Lordships”. The Earl of Cork and Orrery added “Like the great Martian machines in H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, the monsters are closing in.” Thankfully (for those of us who appreciate monsters), Lord Reigate failed.

102 Petty France is asymmetrical, angular and makes no concessions to the Georgian row houses of Queen Anne’s gate. It’s a big, assertive building which succeeds in its job as a symbol of government authority and a landmark on the local skyline. Walking West from Westminster Abbey, the building draws the eye. From the North, the corner tower, resembling a knight’s helm, rises above the trees of St James’s Park. It also dominates the skyline of Green Park and is even visible from Hyde park. The heavy massing of the projecting first and second floors presents visitors with a striking bunker-like solidity. The Earl’s science fiction comparison is appropriate. The building has a unique personality lacking in most other London office buildings of the time. It’s more impactful than, for example, the works of Richard Seifert.

102 Petty France was designed as flexible office space around three cores, modification of the structural frame proved unnecessary. | Photo via Wikimedia

When the Home Office decided to move to a new headquarters in 2003, the cost of demolition outweighed traditionalists’ calls to demolish 102 Petty France. Extensive modifications were made for its current occupants, the Ministry of Justice. The building was refurbished to accommodate 2,400 staff. A multi-services chilled beam system was installed to upgrade office services. The modifications left the original character of Spence’s design intact and 102 Petty France is now an excellent example of how a Brutalist building can be recycled for the modern era.

A structure that is hard to love, but historically important and symbolic of changes in British society since it was built. | Photo via Leicester City Archive

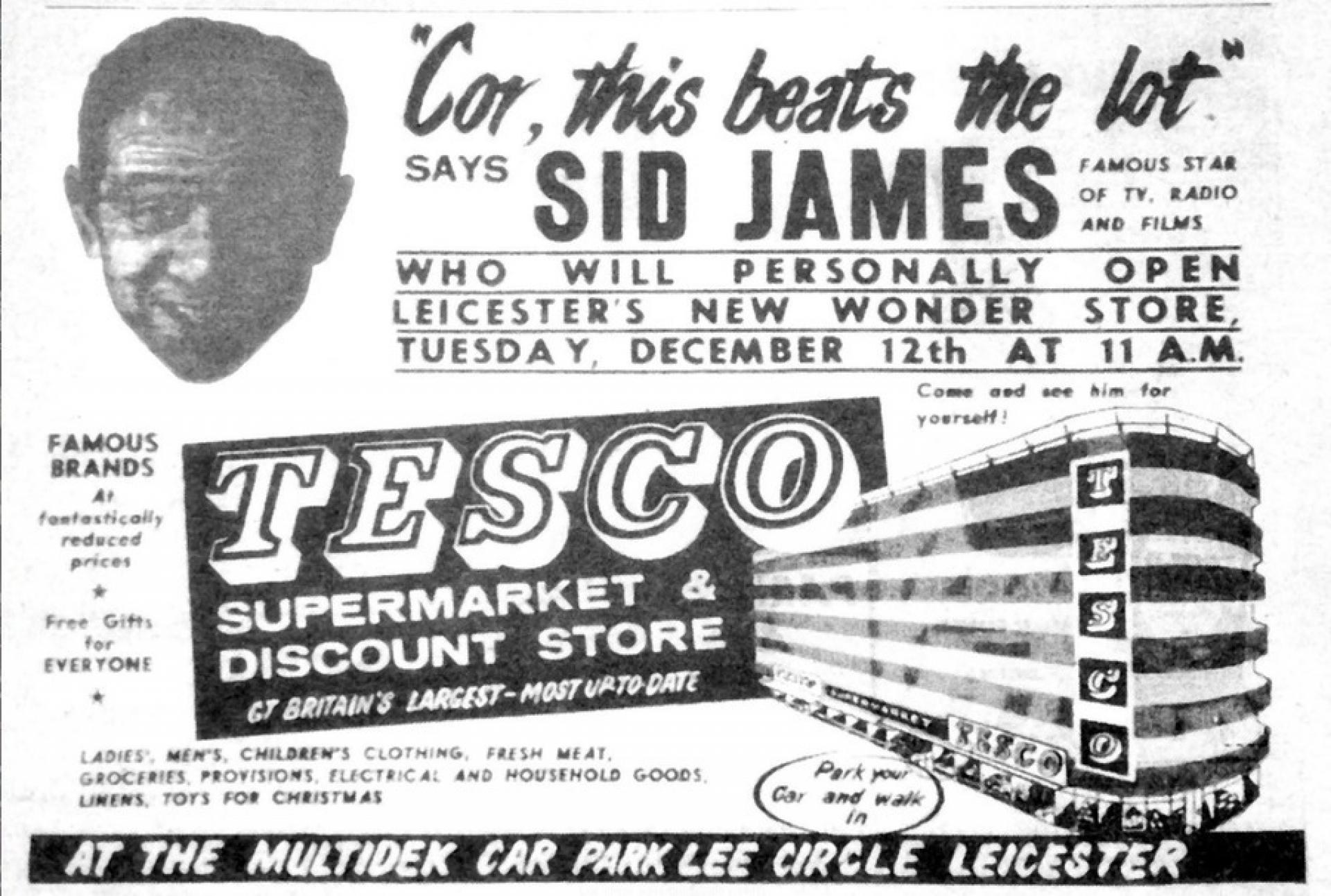

Today, Lee Circle car park appears totally unremarkable to the casual observer, but the Tesco store and car park that opened there in in 1961 was a pioneering experiment, noteworthy for many reasons. A crowd of over 2,000 turned up to see Sid James, star of the Carry On films, open the store in 1961. The supermarket was the chain’s first expansion outside the Southeast. It entered the Guinness Book of Records as the largest store in Europe. Combining a supermarket and a homewares store, with the six-tier Auto-Magic multi-storey car park above providing space for 1050 cars, this was an entirely new retail format in the UK. The opening of the store marked the beginning of self-service shopping in the UK: for the first time, customers could browse alone, filling their own baskets or trolleys. The car park was the first in Europe to be fully automated using coin-operated barriers. Customers refuelled at the forecourt petrol station and used the (also automated) car wash. This was shockingly modern stuff for 1961 but it would become the norm over the next decade. It also illustrates the extent to which the car was prioritized in British town planning at the time, which would be a key factor in Lee Circle’s eventual decline.

The store and car park were integrated so that staff could take customers’ purchases directly to their cars. | Photo via Leicester City Archive

Details of the architect are elusive, but Lee Circle’s double-helix design (where cars ascend on one spiral ramp and descend on another, without meeting) shows they were probably inspired by the Fiat Lingotto Factory, designed by naval engineer and architect Giacomo Matté-Trucco in 1923.

The efficiency of Lee Circle’s double helix design meant that even at the peak of its popularity in the mid -1960s, queues were rare. The same cannot be said for car parks using the grid system. The complex also housed a bowling alley which featured in Ray Gosling’s 1964 film 'Two Town Mad’ (comparing Leicester and Nottingham), illustrating Leicester’s status as a truly modern city.

Lee Circle certainly presents a flowing maritime profile, like Streamline Moderne stripped down to the bones. | Photo via Leicester City Archive

The Tesco store closed in the early 80s (today the unit is occupied by a fabric wholesaler) but the car park remains, its concrete weathered and patched. It is still open but under-used. Shoppers were drawn back to the historic centre of Leicester by the Haymarket Shopping Centre (1973) and the Shires Centre (1991), both of which offered parking, and importantly, convenient access to newly pedestrianised shopping streets. The nearby county court and benefits office closed in 2007, reducing demand for parking further. The future of Lee Circle is under threat. Its opening was probably the heyday of this underdeveloped quarter of Leicester, where Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man, was born a hundred years before the car park.

Ross Nesbitt was born in Scotland and lives in Nottingham, England. He likes to take photographs and has posted his work on Scavengedluxury since 2010.