FOMA 25: Unseeing in the Cypriot Contested Cities

This FOMA is dedicated to the modernist architecture in Cyprus. Socrates Stratis is in search of the unseeing architecture and the cities following the novel The City and the City by China Mieville.

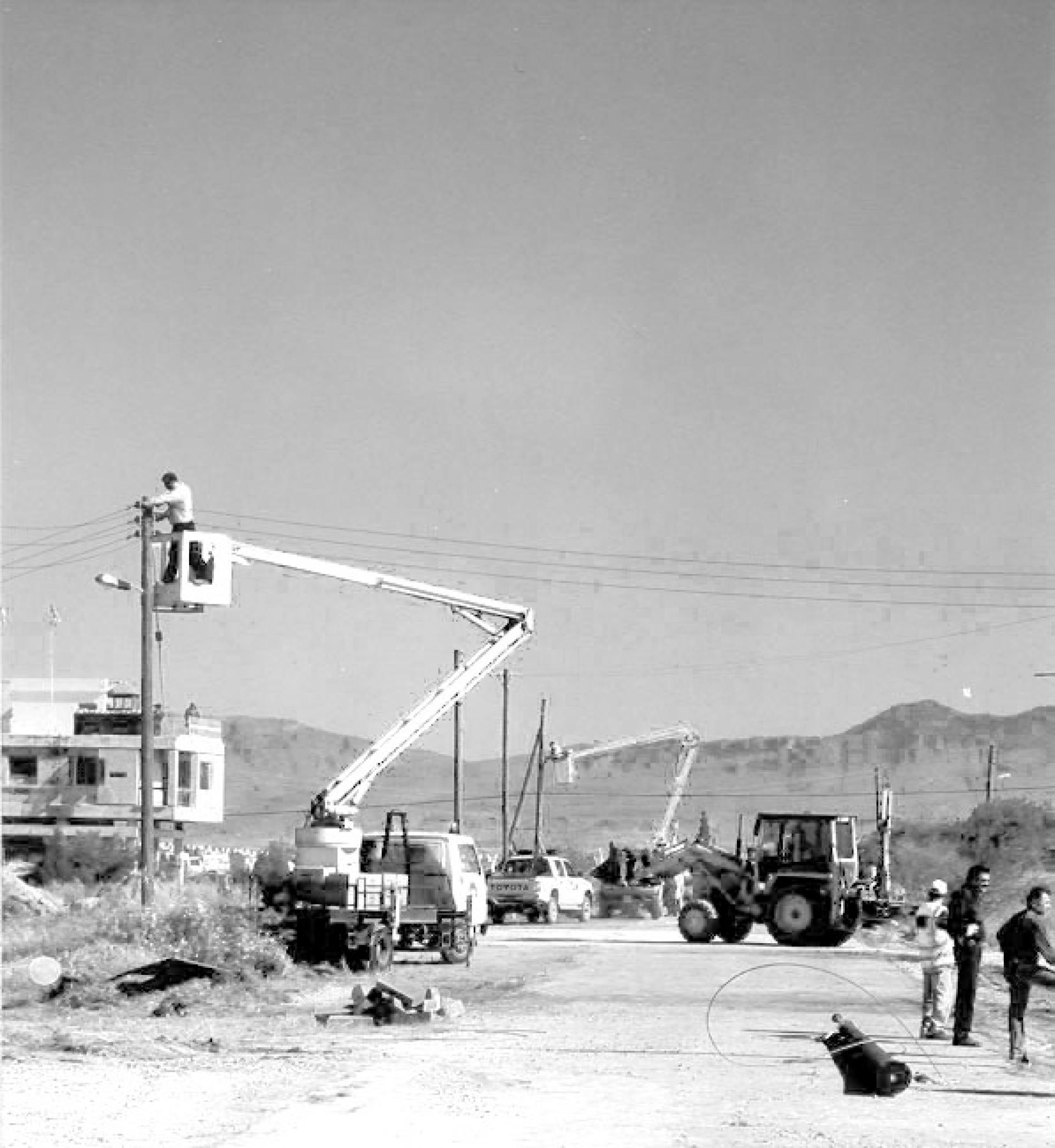

Opening a passage through the UN-Buffer Zone at Agios Dometios, Nicosia in 2004. | Photo by Socrates Stratis

Unseeing in the city and the city

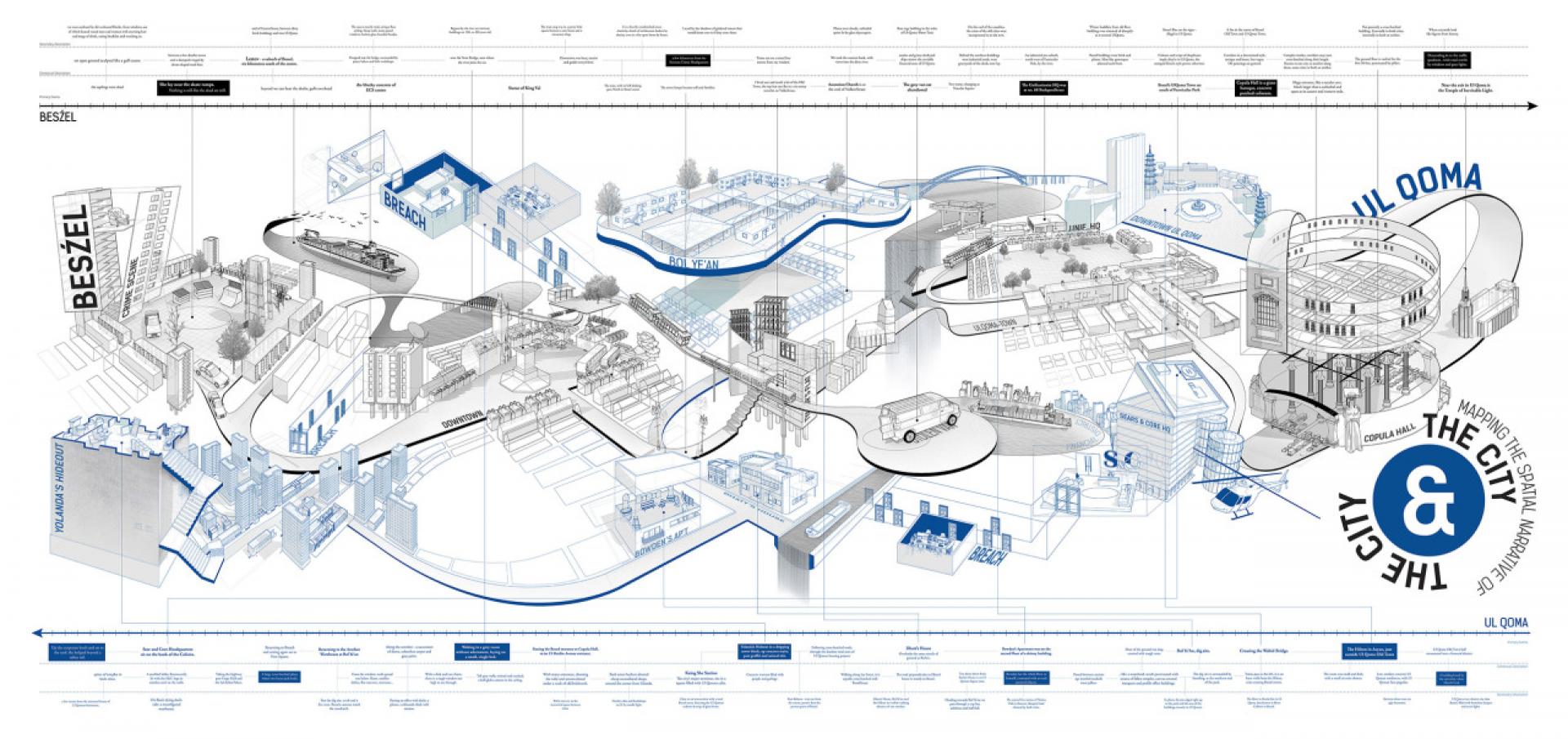

In his novel Mieiville describes the unseeing as the ability of taking out of one’s sight and suppress from one’s memory any presence of the other city, its inhabitants, buildings and activities. Any attempt to see the other, even accidentally, is considered a crime like commit a murder. A secret power, the Breach, vanishes any trespassers. The story begins with inspector Borlu from the police department of the city of Besźel, having given permission to investigate the crime of a killed young lady in the city of Ul Qoma. The reader is kept in the dark, regarding the proximity of Besźel and Ul-Qoma but well informed about the precise and controlled ways of crossing over to the other side.

Besźel and Ul Qoma occupy the same space with the same streets but different names. | Photo via Simon Rowe

This FOMA will present the practices of unseeing Cypriot modernist architecture as manifestation of the Cypriot conflict. Cypriots, both Greek and Turkish speaking, learn already from childhood how to unsee the other, entering into a conflictual process of perpetual forgetting, negation and suppressing the presence of others. In Cypriot cities, like in Besźel and Ul Qoma, exist different names of the same places. The actual condition of six modernist buildings in Cyprus will help to understand how conflict is related to practices of unseeing at three different levels; territoriality, property with its representation and inaccessibility.

Cypriot Modernist Architecture Caught in a Perpetual Conflict

Architecture is quite often a vehicle of consolidating States’ agendas into space. Building the Republic of Cyprus in the 1960s, went hand-in-hand with the establishment of the modernist architecture. Infrastructures, public buildings, tourist developments and single housing were part of the State’s foundation. Rather often, the processes of designing such projects were caught in the Cypriot post-colonial conflict. There is on-going work in Cyprus regarding the role of architecture and conflict [Stratis], including role modernist architecture and its relation to the Eastern Mediterranean post-colonial politics [MesArch LAb].

Cyprus in fragments. | Source AA&U

The Cyprus’ conflict milestones are the inter-communal fights in 1963. The military putsch instigated by the Greek Junta and its local supporters followed by the Turkish invasion in the summer of 1974. The north part of the island is currently under the control of Turkey, shadowing over the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus that is a non-recognized internationally except by Turkey. Because of the 1974 Turkish invasion, the north part of the island was emptied by its 162,000 Greek Cypriots inhabitants who were forced to move to the south. The population in the south part of the island is 856.960 according to the 2011 population census of the Republic of Cyprus. In 1974 about 48,000 Turkish Cypriots were displaced from the south to the north to join the 70,000 Turkish Cypriots in the north. They had to cohabit with a much bigger number of Turkish settlers moved to the island from Turkey [Gürel, 2009]. The Turkish migration created second class citizens and a colonization tool for Turkey by outnumbering the Turkish Cypriots. The population of the north part of Cyprus reaches 300,000 according to 2011 UN demographics. Any population data regarding the incoming Turkish population is contested between the two communities, being one of the main obstacles to any political agreement.

Unseeing Buildings and Cities

For Greek Cypriots Famagusta is Ammochostos, Kyrenia - Kerynia, Morphou - Morphou, Nicosia – Lefkosia. For Turkish Cypriots the names change, Famagusta is Magusa, Kyrenia - Girne, Morphou - Guzelyurt, Nicosia - Lefkosa. Larnaka seems to hold the same name for both Turkish and Greek Cypriots. Some of the Turkish names were official before the 1974 war, while others, mainly on the north part, were created after the war. According to the social anthropologist Yael Navaro Yashin (2012) such a practice is based on a policy for erasing Greek Cypriots’ ownership and traces of use, establishing therefore, the legitimacy of a make-believe space for the Turkish Cypriots.

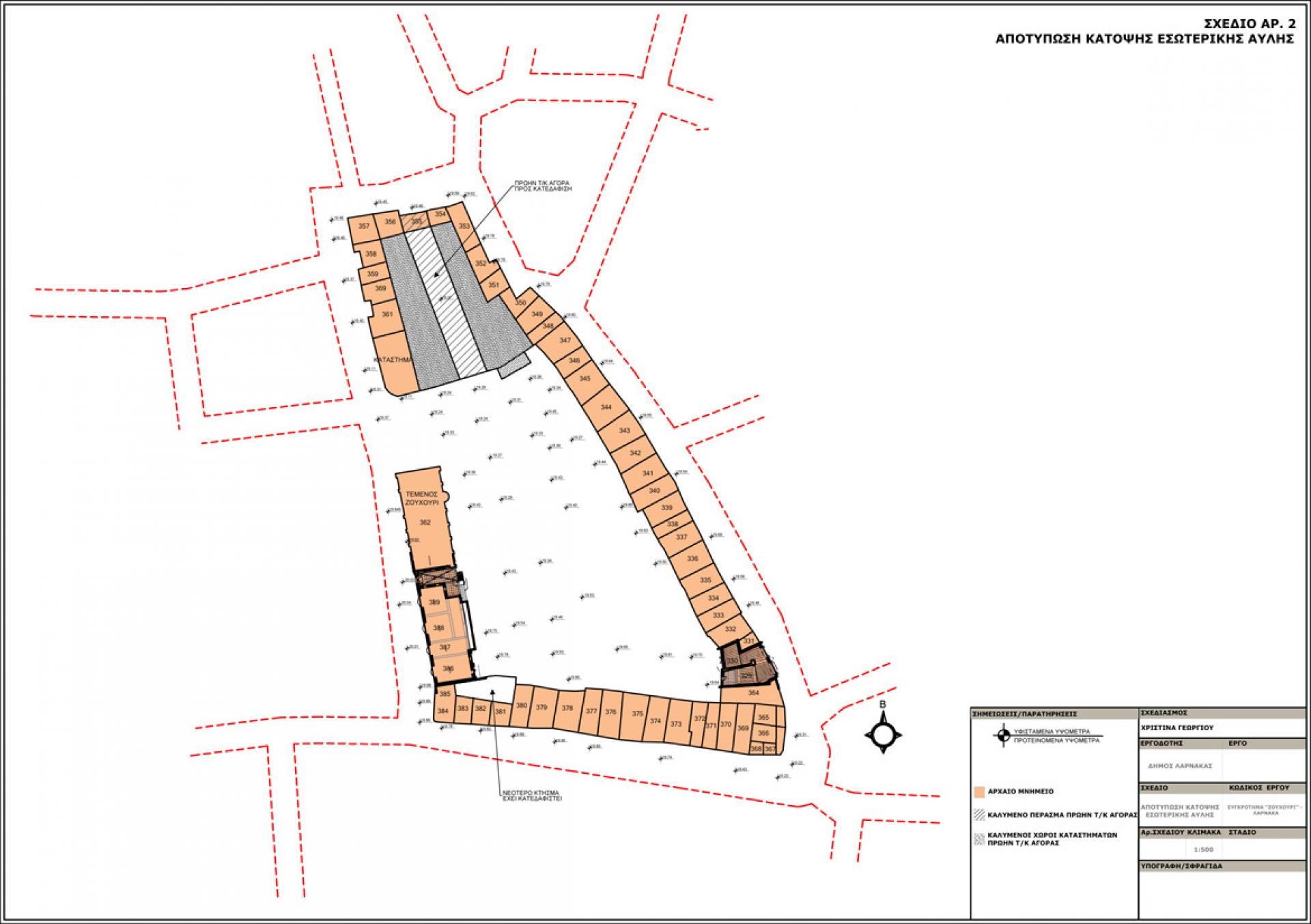

The six modernist buildings that embody the island’s conflict, were built between late 1950s and early 1970s. They are located in Famagusta, Kyrenia, Morphou, Larnaca and Nicosia. The municipal halls built by the Greek Cypriots after the 1963 conflict are located in Famagusta, Kyrenia and Morphou. The Municipal market in Larnaka is located in the city centre at the edge of the former Turkish Cypriot Zouhouri quarter. The two residential buildings are trapped in Turkish military zones and they are close to the check points of Nicosia and Famagusta, where people cross the demilitarized zone between the south and north controlled by the United Nations.

Pre-1974 waterfront tourist development of Famagusta. | Photo via Press and Information Office, Government of the Republic of Cyprus – PIO

Imaginary and Physical Territorialities: The Municipal Halls

The three municipal halls of Famagusta, Kyrenia and Morphou were hosting the Republic of Cyprus’ municipalities until the war of 1974. After the 1963 bi-communal conflicts, they were serving mostly the Greek Cypriot population. Since 1974, they host the municipal functions of the Turkish Cypriots. The unseeing of three municipal halls has a double interconnected connotation. The first is the removal of the public buildings’ initial symbolic value associated with the Greek Cypriots and the addition of a new symbolic value linked to the Turkish Cypriot claim of governing the occupied territories. The second is the creation of exiled municipalities by the Greek Cypriots in the south part of the island. The Famagusta municipality is hosted in Limassol, the Kyrenia and Morphou ones are located in Nicosia.

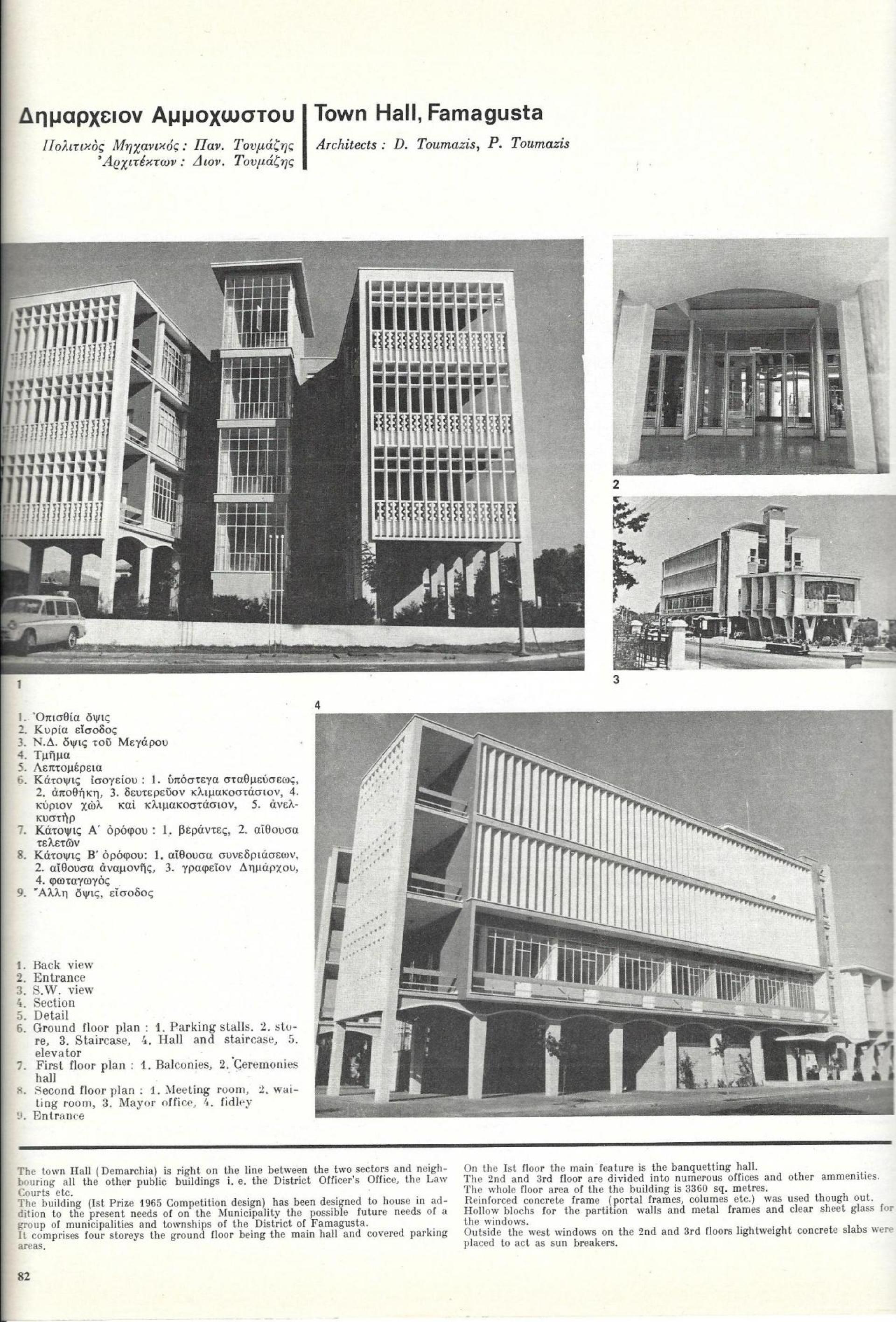

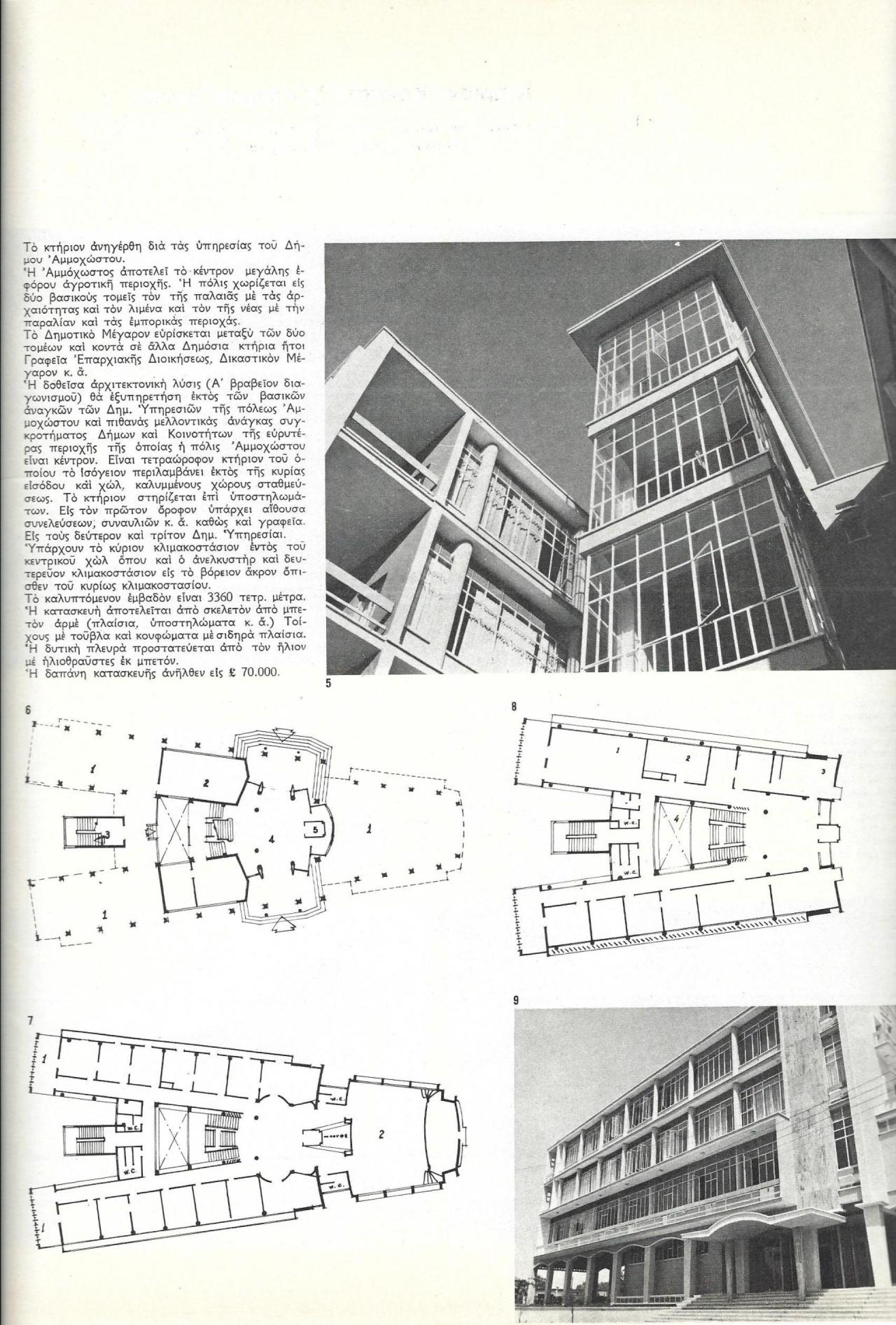

The Famagusta Municipal Hall (1966). | Photo by Socrates Stratis

Despite the displacement from their cities, the Greek Cypriots have kept their municipal authorities as a mode of resistance to Turkish occupation, seeking return to their homelands. They elect their mayors and have their municipal counselors organizing all sorts of events for the displaced inhabitants. They reject the actual control of their municipalities and cities by the Turkish Cypriots and Turks, keeping a distorted memory of their pre-1974 hometowns. They have developed their imaginary territorialities.

The Municipal Hall is organized in a V shape floor plan, following the geometry of the two convergent streets. | Photo by Socrates Stratis

The Famagusta Municipal Hall is located along the main street with the administration buildings constructed during the British mandate. The street connects the walled city of Famagusta, that used to be populated mainly by Turkish Cypriots. The Varosha area, that used to be populated mainly by Greek Cypriots, is actually inaccessible due to its control by the Turkish army. The municipal building sits in an area that is supposed to be handed over to the administration of the South Region, to be created under the Federal State of Cyprus, where the Greek Cypriots will be a majority. Unfortunately, this new political model is falling short since the negotiations between the two communities have stopped in 2017.

The west facade of the two top floors of the Municipal Hall are covered with slim concrete louvers. | Photo via Architectoniki, Vol 55, 1966, p. 82

Only a few critical urban projects, commonly produced by the two communities, address the city’s future when the island will be reunified. The Hands-on Famagusta project has made explicit the need to include in the negotiations for the new Federal Cyprus, the role of governance of Famagusta as an undivided territory, abandoning the ethnically binary way of administration [Stratis, Akbil]. The on-going discussion seems to adopt the creation of separate Turkish and Greek Cypriot administrative territories under competing municipalities [Stratis]. The future of the municipal hall remains ambivalent.

Famagusta Municipal Hall has a lower volume at the front and two linear ones on both sides. | Photo via Architectoniki, Vol 55, 1966, p. 83

The Municipal Hall in Kyrenia constructed in 1969 is a product of donations. It was donated by the Greek Cypriot Zena Kanther. It is located in the public garden of the city, a donation by Scottish inhabitant George Ludwig Huston. The main entrance opens into a public space overlooking the old city and the sea. Its back side opens into a garden. The two-floor building is organized into two superimposed and shifted square-plan volumes, creating different conditions along its perimeter.

Kyrenia Municipal Hallis a free standing object with all its sides exposed to the square.| Photo by Socrates Stratis

Since 1974 Kyrenia Municipal Hall has been painted in white, covering its original sand-like finishes.| Photo by Socrates Stratis

When talked to the Greek Cypriot exiled mayor in her office in Nicosia, she remarked that she had not gone back to her hometown since 1974. The Greek Cypriots refuse to see the 44 year old appropriation of the building by the Turkish Cypriot community, considering it illegal, where the Turkish Cypriot tenants unsee any use of the building before the 1974 war. Kyrenia will be part of the North Region with Turkish Cypriot majority in case of a political agreement based on the Cyprus Federal model. It remains rather vague whether the local authority structure of such Federal model will be based on the European acquis of local governance, allowing for co-habitation of citizens coming from various ethnic groups.

The modernist two-floor tall apartment building of the Morphou Municipal Hall. | Photo by Socrates Stratis

The Morphou Municipality Hall is located in the old city centre. The Guzelyurt’s inhabitants, mostly Turkish settlers and also Turkish Cypriots displaced from Polis Chrysochous, have been using the rented apartment building as municipal hall for the last 44 years. Before 1974 was also used by the Greek Cypriots.

Morphou Municipal Hall was built during the construction boom in the 1960s. | Photo by Socrates Stratis

The actual municipal building has shop-like ground floor and a first floor with offices around a courtyard. | Photo by Socrates Stratis

Morphou Municipal Hall is situated between three roads following the geometry of the convergent streets. Surprising fact is that the municipality was operating in a building for 44 years without any issued floor plans. During our first visit, I had the feeling that the occupants were in a sort of a temporal appropriation of a building that they found ready for use in 1974. The exiled municipality of Morphou is located in another apartment building in Nicosia. The Morphou area is supposed to be part of the South Region according to the failed United Nations plan of 2004. However, the on-going investments in construction and infrastructures by the Turkish Cypriots and Turkey are means to cancel out such potential.

Making a Market Invisible

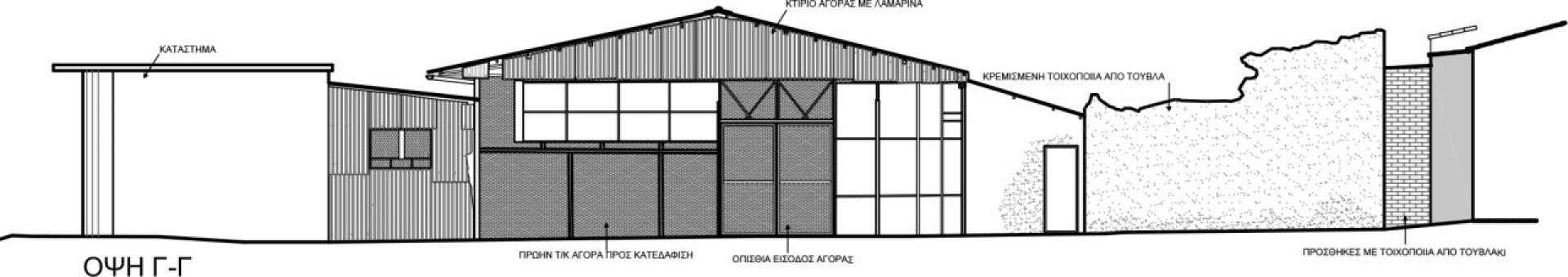

The fourth building of the group under discussion is a small Turkish Cypriot Market in Larnaka built in 1955 and located in the city commercial center, just next to the major city market.

The complex was used as the Turkish Cypriot market up to 1963. | Photo by Chrysanthe Constantinou and AA&U

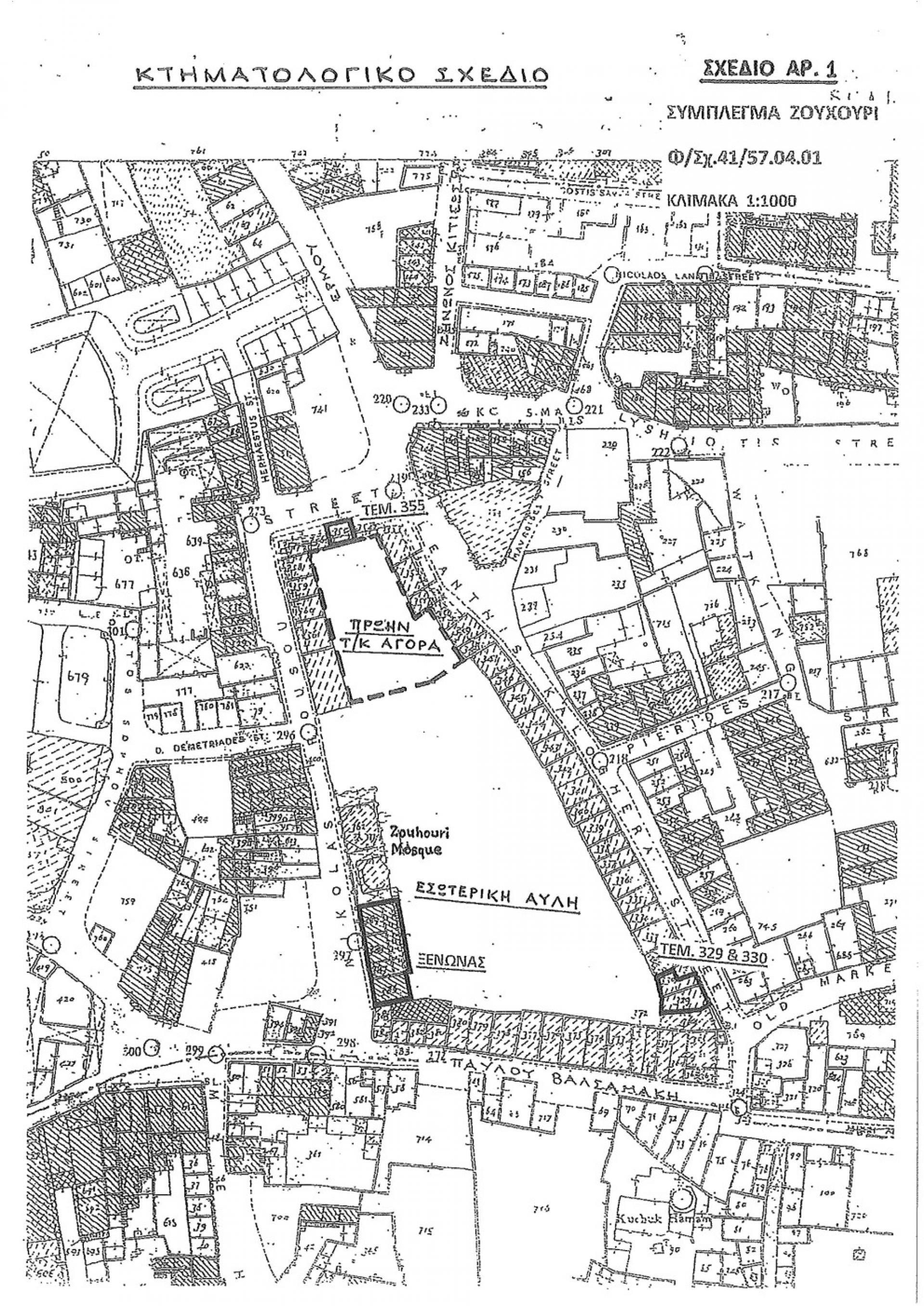

The owner of the building is Evkaf, the institutional body managing the Muslim religious land in Cyprus. The building permit files show that the construction was meant to be for commercial shops. It is not clear how it was used from1955 up to the 1963 bi-communal conflict, when the Turkish Cypriots were forced to move further west, trapped in an ethnic ghetto. This small ignored market doesn’t exist in the official cadastral plans, where we find instead, the site plan with the former traditional buildings, that were demolished probably in the 1950s to build the unseen market.

The market has an interesting scale, consisting of a series of shops completing the historic urban block of Zouhouri (courtyard view). | Photo by Vasilis Pasiourtides

The urban block also contains one floor stone-built workshops, a two-floor tall hostel and the Zouhouri mosque. They all surround a run-down courtyard, used for parking. The Market building completes the north edge of the urban block, creating an entry to a covered space leading to the courtyard. The market is occupied by Greek Cypriot tenants, some displaced from the north part of the island in 1974, some from the demolished market next door.

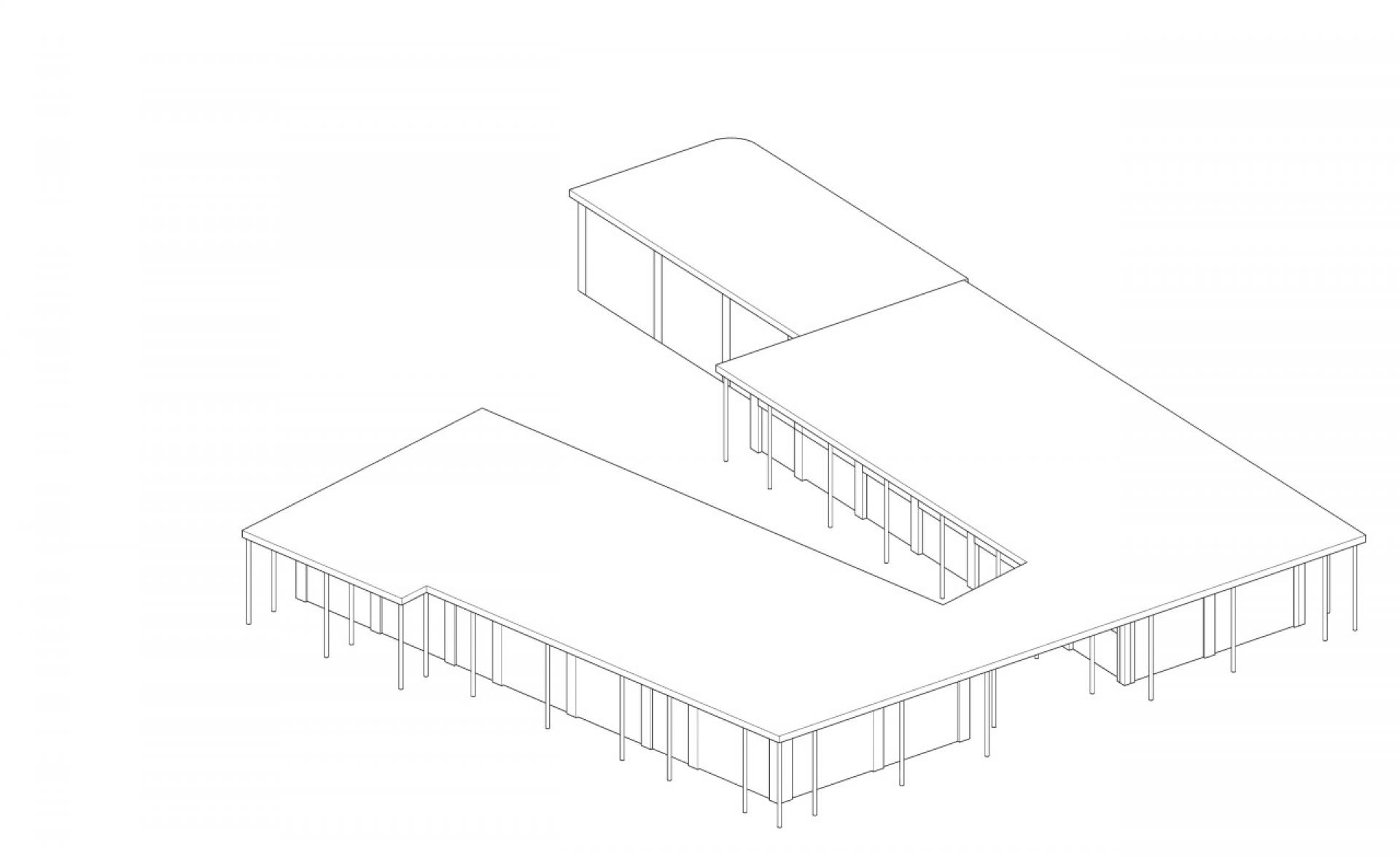

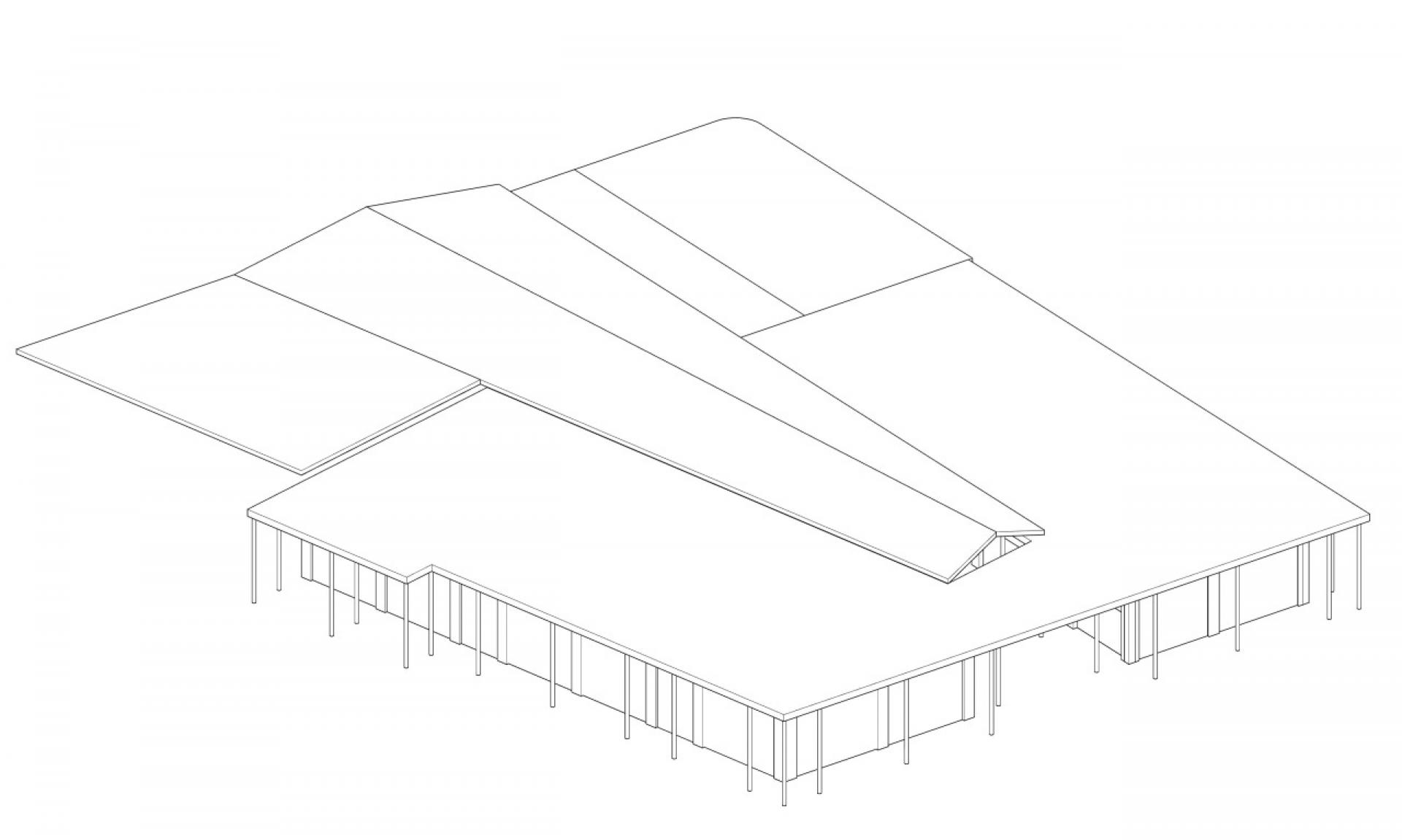

The roof, supported by very thin metal columns, creates a narrow covered space along the streets. | Drawing by AA&U

The roof that covers the courtyard space, is a later addition.| Drawing by AA&U

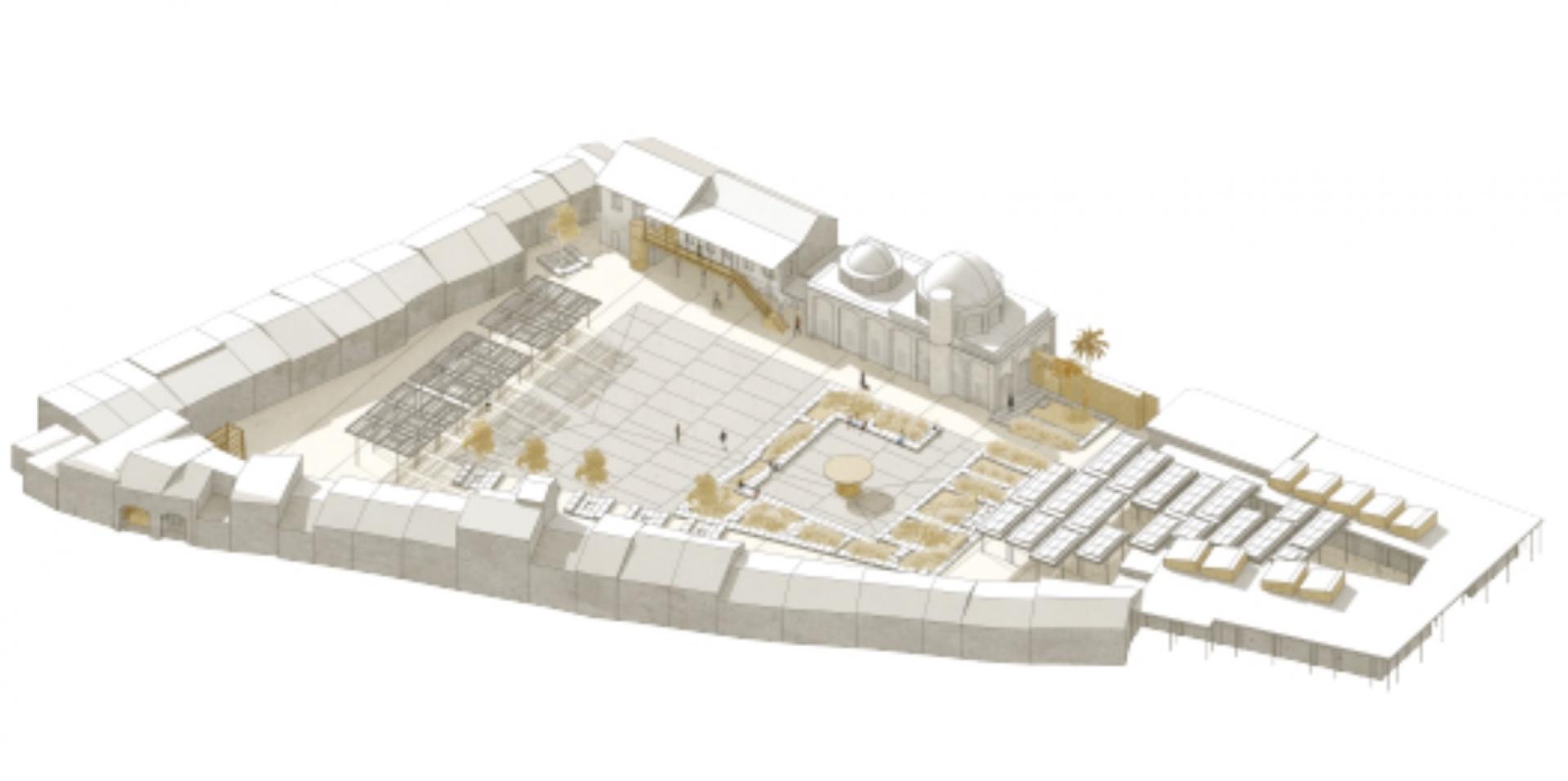

Larnaka municipality launched a competition in 2018 for the redevelopment of Zouhouri courtyard including the market. | Drawing by Municipality of Larnaka

I have participated in the competition with the AA&U agency, using our proposal as a critical political comment regarding the on-going conflictual use of Greek and Turkish Cypriot ownerships by the opposing communities. Both communities fail to bring into public debate both the controversial actual use of such properties as well as their potential in supporting the scenario of the island’s reunification. Since 1974 the agency of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Cyprus has managed all Turkish Cypriot properties in the south part of the island. The State agency rents out the Turkish Cypriot assets to the Greek Cypriots. The non-transparency of the procedures has led to many scandals of financial misuse. In the north part of the island, the Greek Cypriot properties, considerably more than those left behind by the Turkish Cypriots in the south, were given out to the Turkish Cypriots and Turkish settlers. The Turkish Cypriot authorities have created a parallel cadastre, non-recognized either by the Republic of Cyprus nor by international courts.

Turkish Cypriot Market. | Drawing by Municipality of Larnaka

In the case of the Zouhouri architectural competition, the monumentality of unseeing was manifested in the competition brief. The survey site plan included detailed plans and sections of the courtyard and of two 19th century-old stone buildings of the block to be restored. The brief also included a detailed drawing of the rundown facade of the back side of the market facing the courtyard. But the plan of the market was missing from the recently surveyed site plan of the Zouhouri urban block. Instead, there was a plan of the buildings demolished in the 1950s. The same buildings’ plan appears in the official cadastral map instead of the 1950s market building. When the competitors had asked for updated drawings of the market, they received an answer by the competition committee, that reminds us of the Breach Authority from the City and the City novel. It urged the competitors to unsee the market and proceed with the given drawings. Retaining invisible the actual plan, the Larnaka Municipality could keep invisible not only the Turkish Cypriot pre -1974 tenants but also the actual ones, getting most probably the liberty to proceed to any eviction agendas.

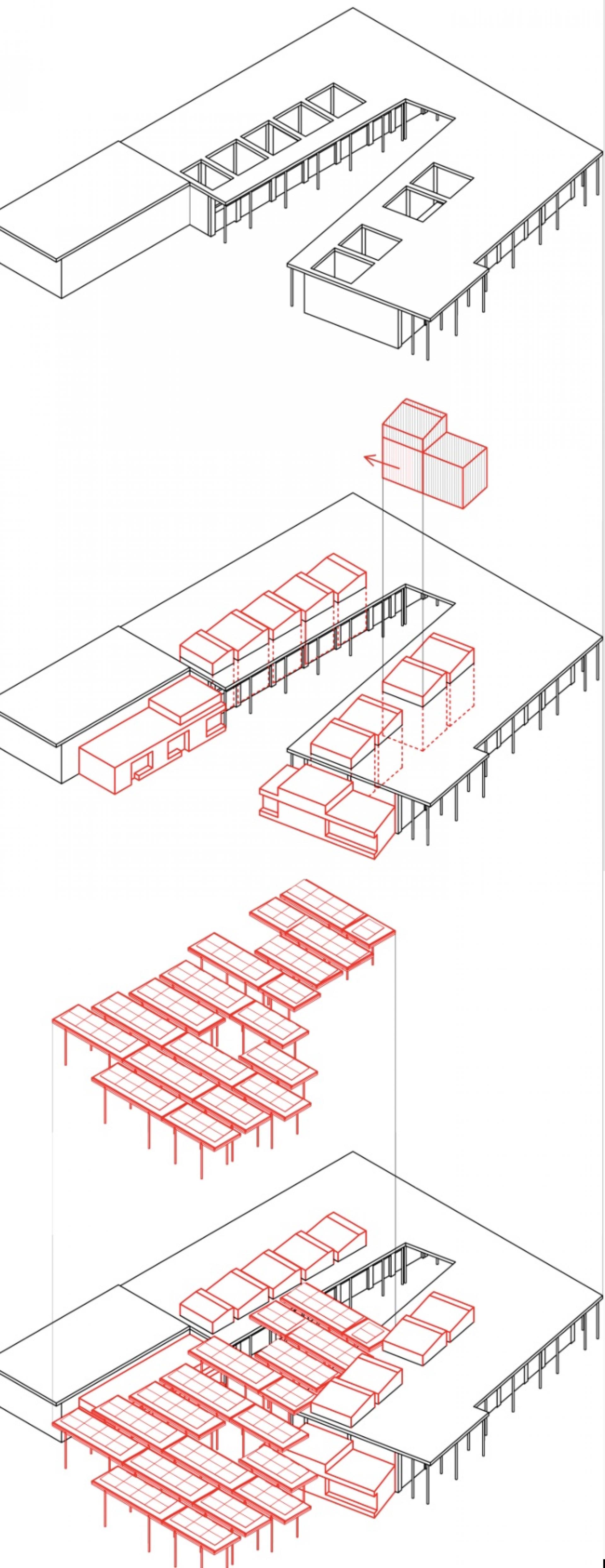

Refusing to unsee the market: The critical proposal for the Zouchouri architectural competition by AA&U: Urban Oasis - Zouchouri architectural competition entry by AA&U.

Not surprisingly, the shiny photorealistic renders of most of the competition entries, including that of the first prize, consolidated the competition committee’s decision to unsee the market. In its place, we see images of the pre 1950 demolished buildings.

The AA&U’s competition entry countered the competition committee’s instructions. We proceeded a meticulous survey of the market and based the proposal on the existing building, offering the plan survey to the city.

The breaching act of the AA&U entry was ignored by the competition committee. It chose to unsee any controversial issues of ownership and its representation. Surprisingly, the AA&U’s entry was awarded with an honorable mention for the overall proposal of the urban block.

Unliving Along the Checkpoints

The two residencies in Nicosia and Famagusta are 1960s suburb modernist architectures, following Le Corbusier’s five points of Architecture. They are both Greek Cypriot houses inaccessible to their owners since 1974, trapped in the Turkish military fenced-off areas and stripped from their content. They are both located along roads, which are part of check points between the north and south parts of the island crossing the UN demilitarized zone. The check point in Nicosia, Agios Dometios, opened in 2004, while that in Famagusta opened in 2018.

The modernist building in Nicosia is transformed into an army post, with doors and windows sealed and walls painted white. | Photo by Socrates Stratis

The flags of Turkey and “TRNC” at the north facade of the Agios Dometios with the plan of the divided island placed between them. | Photo by Socrates Stratis

In the case of Nicosia, the Turkish army turned the residential building into a new observation post, profiting from its adjacency to the Agios Dometios checkpoint. The modernist roof terrace is turned into an observation deck. By making visible their authority over the territory to the passing-by car drivers, they brought to the foreground the unseen modernist building.

The Famagusta Derynia checkpoint connects Derynia with the southern suburb of Famagusta, part of which is Varosha, the ghost part of the city. Since the opening of the check points in 2003, the Greek Cypriots visit Famagusta to see their homes. The same stands for the Turkish Cypriots, who cross to the south part of the island. The Greek Cypriots, whose homes are located outside the ghost part of the city have the chance to access them and find other people leaving inside for the last 44 years. There are 5,103 buildings hidden behind the modernist waterfront high-rise buildings. [Stratis].

The check point road towards the Famagusta city centre passes along the back side of the fenced-off area of Varosha, revealing another urban reality from that of the coastal high-rise buildings that Greek Cypriots have associated with the image of Famagusta. | Photo by Socrates Stratis

Facing sprawled empty suburban detached houses behind the fence. | Photo by Socrates Stratis

Very close to the checkpoint we run into a modernist house rather faithful to the Villa Savoye architectural paradigm. The practice of unseeing entails a new proximity of the trapped modernist buildings with the act of crossing to the other side. Their adjacency to the checkpoint roads, like the case of the Cupola between Besźel and Ul Qoma, condemns them to be looked at thousands of times and to be forgotten quite as many.

Unseeing Modernist Architecture Sustains the Cypriot Status-quo

”… inspector Borlu from the police department of the city of Besźel runs into an inconvenient truth. The assassinated girl was part of an American excavation expedition that had discovered a third city, Orciny. Orciny exists mysteriously in the interstices of Beszel and Ul Qoma, unseen by all inhabitants of the two cities. The mysterious Orcinians seem to use all means to keep their secret, like that of unseeing. It sustains the status quo of the two cities” writes Mieiville.

Unseeing practices in Cyprus, examined through the presented examples show that they pertain conflictual imaginaries between Cypriots. The modernist architecture in Cyprus has gone hand-in-hand with consolidating the State’s agendas in the 1960s, but also the agendas of the British Colonial Regime up to 1960. Unseeing practices become part of such consolidating agendas and invest in the continuation of the status quo on the island. Through the Municipal Halls, we have realized how the embodiment of physical and imaginary territorialites takes place, creating conflictual conditions instead of potentials of co-governing. In the case of the Municipal Market in Larnaka we have understood how a building can disappear from maps and institutions, a victim of an unresolved ownership conflict. When we look thousand times at the two residential buildings along the checkpoints, and we forget them as many times, we realize the powerful normalization processes of status quo in conflict areas. The agents keeping strong such processes remind us of the Orcinians who control the status quo of Beszel and Ul Qoma.

I couldn’t say who could be the Orcinians on the island. I am convinced that they much profit from the deeply conflictual imaginaries of the Cypriots’ urban everydayness, for which the processes of unseeing modernist architecture in Cyprus have their contribution.

Socrates Stratis PhD. is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Architecture, University of Cyprus. His research focuses on the political role of architecture and urban design in supporting the commons in uncertain, contested urban environments. He is one of the main founders of the agency AA&U, director of the Laboratory of Urbanism (LUCY) and part of the Imaginary Famagusta (I.F.) team. He is the editor of the Guide to Common Urban Imaginaries in Contested Spaces. He curated the Cyprus pavilion at the 15th Venice Biennale of Architecture entitled Contested Fronts: Commoning Practices for Conflict Transformation. He is member of the scientific committee of Europan Europe. Among his implemented urban design projects is the winning project of Europan 4 for the redevelopment of the public spaces and services of the Heraklion old city waterfront in Greece.