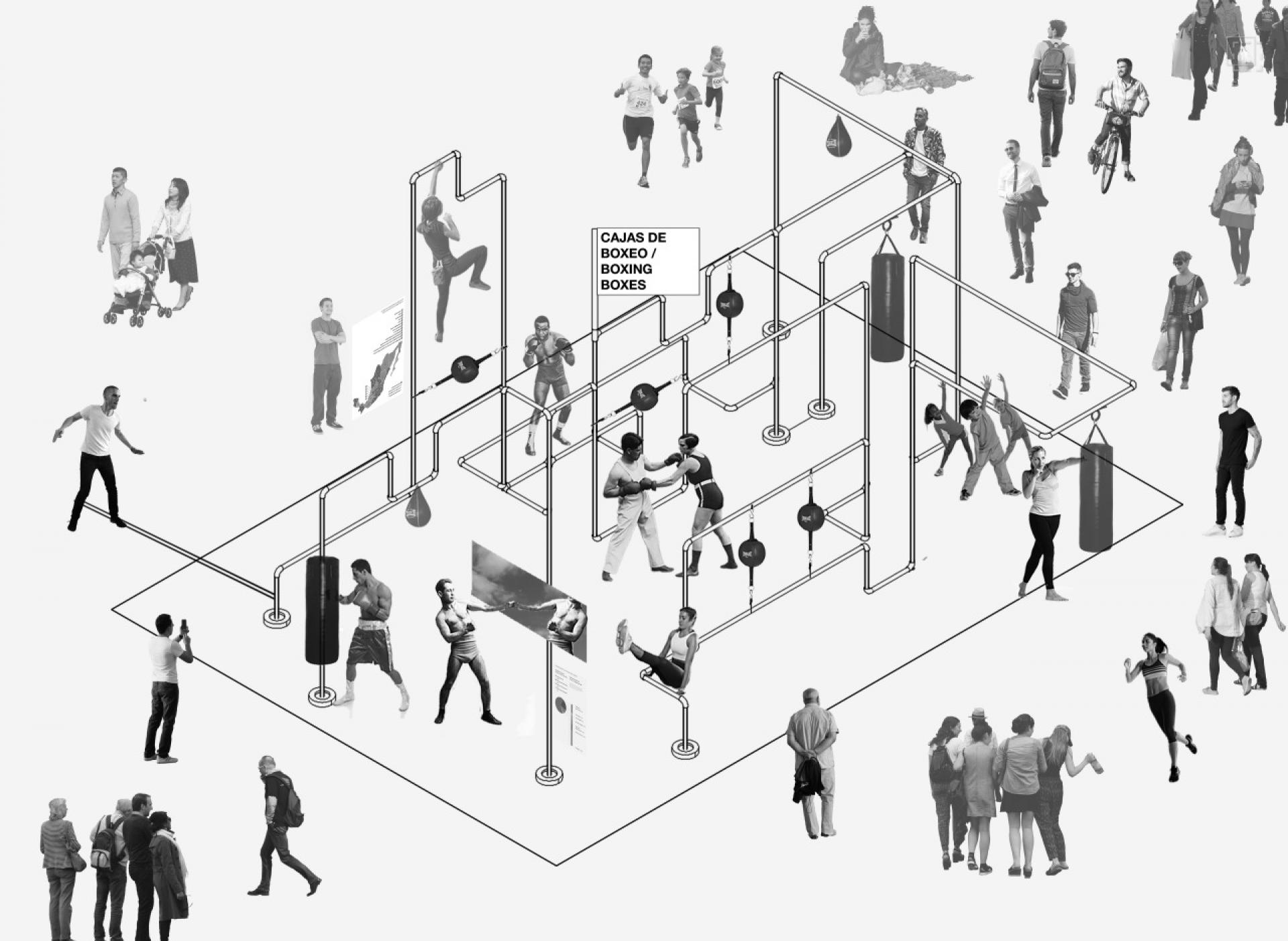

Boxing Boxes

is a temporary associated project of the last Lisbon Architecture Triennial, which was accepted by the community of the Portugal Novo neighbourhood and in such way became a permanent public installation.

A drawing of the installation by © Daniel Languré

The Mexican architect Daniel De León Languré started this process of the social cohesion of the community of Olaias, a marginalized area of Lisbon, creating an open-air gymnasium that involved local agents and inhabitants. We meet Daniel in Lisbon during the official opening of the installation.

Where did you study and what did you learn in Mexico City?

DDL: Studying in Mexico City is like a huge opportunity, as the city is one of the biggest in the whole world and there is always an opportunity for experimentation in the field of architecture and arts. After finishing my studies at the university I tried to develop an office, where I could experiment in these fields. There is always a sense of tolerance in the architecture of Mexico City, sometimes due to the earthquakes, but also because of the lack of planning. One could learn how to take advantage of these things and experiment with them in order to find new solutions and answers.

Does have an education in Mexico a double meaning while there is a possibility to study either at the public either at the private university?

DDL: I think that there are some very good public universities, where you can learn a lot from very well-educated professors, which also studied abroad. UNAM is a huge public university, where you can meet a lot of people with different interests and that can enrich your perspectives. You can’t have this opportunity if you frequent a private university as the faculties are smaller and you can’t compare the resources of private and public institution.

Official opening of the installation. | Photo © Fabio Cunha

In your projects you work with communities therefore are your social projects like an urban acupunctures than built houses; Why?

DDL: I was always interested in the public realm but as a junior architect I didn’t had a chance to make project in a legal or formal way. At the beginning I started to experiment with my colleagues, first we did some small experiments mostly payed with our owns salaries. We acknowledged that if want to make some changes, that would last longer and with a greater impact on our community, we should start to think in the kind of commissions that could be the ones we should look for in order to had better and stronger consequences. Well, there were none, we didn’t win no competition. But maybe that was not even the right question to ask or at least that was not the one that interested us the most, and we started to work in self-committed projects. The project doesn’t need to be just buildings, we could work more with experiments.

You have been present at the Lisbon Triennial of Architecture 2019 with a project Boxing Boxes?

DDL: The project is much older that you have seen it in Lisbon. It has started as a research and finished as a build installation; a continuous steel tubular structure placed in a sand box in the Northern neighbourhood in Lisbon. We use a “Boxing Boxes” name to avoid the gym term. It is not a gym but an open typology. Some people mentioned me Lisbon Architectural Triennial and how the team would be compatible with the project and that is how we started to think in Lisbon as a place to materialize the research.

It was very difficult for me to manage this project from so far away but the it was a great help that the Lisbon team, composed mostly by the local young atelier Gato Morto and Ensaios e Diálogos Associação, explain me more about places and problematics. We had frequent reunions via Skype with organizational team of the Lisbon Triennial, members of the neighbourhood of Portugal Novo, boxing gym managers, among others. The Lisbon team had reunions with the neighbours to explain which demands were included into the design.

You were entering into this public space of the specific neighborhood in Lisbon?

DDL: The project is located in the Portugal Novo neighbourhood, a social housing complex done in the 1970s that has never been completed. It left homes, areas, educational and recreation facilities unfinished. People have told me that today is almost the same situation as it was in the 1980s. There is a sense that time hasn’t passed in 30 years. Due the irregularity of those settlements a great number of vulnerable African, Indian and Roma immigrants have come to occupy the neighbourhood and had difficulty with communication and interaction.

Most of the strength of the project is due the location. In the beginning I had an idea that maybe the project could be placed in a more central place in Lisbon or even close to the main museums like MAAT Museum near the river. But later we felt that if it was there it could almost betray its own principles. We were searching for a place with the power of negotiation where community shall benefit from the project and accept it because they had a lack of infrastructure.

Just before we selected Portugal Novo as a definite point of intervention was the help with the Lisbon team that told me more about the neighbourhood, their experience in knowing some of the actual neighbours, the possibilities of a greater impact for both the team, neighbourhood and Triennial and finally the interest associations such as Aga Khan Foundation had in the implementation of a temporary project there.

What is important in the planning of the project?

DDL: The most important thing I believe is the management. I was always afraid that the people from the neighbourhood might think on why should they accept a project from a strange Mexican guy, who has ambitions to experiment in their neighbourhood and invade their public space. Sometimes they were asking if they will need to pay for the use of the installation or if they will need tickets to use it. They also asked if it is going to be temporary or permanent and we were not clear about the answers. That shows how fundamental were the management skills of both Mexico City and Lisbon team towards the community. We involved their wishes into the design, supporting their needs to modify the installation if they want. I was also communicating with people after and before the inauguration not to make them feel being used as now the installation is theirs.

How did you communicate with the audiences to attract them into the project?

DDL: Online, with calls also writing many emails. We as a team from Mexico City and Lisbon try to present them the project together. For example: I made some architectural images in order to present the project, but these images were understandable only for architects and not for general public. Therefore, after some conversations I had to make some other images, texts and strategic communications thinking in a broader public.

I landed in Lisbon one week before the opening, the installation was built in four days. It was very quickly. I wanted to be there when the first type was installed because I could solve doubts and be able to meet and talk with the neighbours. I was able to take care of the installation but also to be aware of the people that were exploring it. In few days we were in Portugal Novo many hours per day trying to have the best results.

We organized some reunions, meeting and introduce the idea to the president of the neighbourhood and to some other important social actors. Finally the opening was organized as a multicultural lunch that allowed people to know each other with the Triennial organizers, journalist, architects, neighbours, people that worked there. We wanted to do it in the horizontal way so we shared the common meal and time.

To talk and to listen. How did you communicate?

DDL: Sometimes in Spanish as some of the Roma immigrants who live there have a strong connection with Barcelona. Most of them know Spanish. With Gato Morto I used to talk in English, and since I know a little Portuguese, they were very kind and helped me translating whenever I neighbor wanted to talk with me. Sophia, Maddalena and Claraluz were very empathetic in that sense, maybe because all of us were actually all immigrants from Mexico, Brazil, Barcelona, Cabo Verde, India, etc.

Is temporality an advantage or a disadvantage in the implementation of this project?

DDL: In this case temporality was both an advantage and a disadvantage. A disadvantage when you realize you can’t plan activities in a long term the activities because originally in two months from the opening the installation was planned to be brought out. You have to schedule all in a few weeks or months. An advantage when you know that the neighbours might be willing to accept the project if you tell them that it will be there just for few weeks.

Thankfully, after the opening they had so many good opinions they started to think that this remporary project could become permanent. We first asked the community what they think about it and when they saw that so many children and adults were interacting with each other and the public realm was not about fighting with the immigrant group but about having a place to discuss common themes as a community, they were willing to accept it as a permanent one but with a possibility to modify it.

The most important thing in the whole story is probably that you got trust from the residents?

DDL: I believe there was a coincidence of getting the trust for the project but also getting the trust from the neighbourhood and the local authorities. I believe there were also a happy coincidence of factors such as the creation of a new local association of Portugal Novo and the search of some legitimacy through some nice and quick results. We manage to integrate a team with them and the communication was therefore much easier.

What shows the Boxing Boxes installation is that you succeeded to connect different generations in the public space; did you plan this or it just happened?

DDL: Although we didn’t plan it, it was in the wish list. We knew that the ambiguity of the installation could facilitate such connection. In the general perception if we had to assign one to each, a playground is more for children and a sport facility is more for adults. One of the greater assets of Boxing Boxes is that its open design can join both adults and children to enjoy a space like this. We wanted to soften and blur the difference between playing and practicing sport since the place gives a chance to experiment with people from another age, another immigrant group and another neighborhood.

Do you have, besides Gato Morto, some other person or group in Portugal Novo that you are still attached and you still communicate with?

DDL: Yes, one example would be Nuno Furtado. He was the president of the neighbourhood society of Portugal Novo called AMPAC Olaias. His family is part of the immigrant group from Cabo Verde and he told me that when he was a child in this neighbourhood, he always had to move to another neighbourhood in order to play. He was very excited about the opening, telling us how well the kids were playing in the installation and how he enjoyed the situation because there was a lack of public life in the streets, which makes the streets feel insecure. With kids playing the parents are somehow forced to be occupy the plaza during the night. All of a sudden, the night was also this time of play, sport and integration. After that he also started to play with children, that was one of the best moments that we had.

Photos © Hugo David