A False Dilemma

As I write this in early July, the public unveiling of the Bežigrad Sports Park project is ending. The extensive plans for this vast new complex near the centre of the Slovenian capital promises an impressive mix of a sport stadium, gyms, offices and apartments in one of Ljubljana’s best locations.

A consortium of public (the Municipality of Ljubljana and the Olympic Committee of Slovenia) and private partners (the businessman Joc Pečečnik and his company) has been promoting the project for more than a decade against strong and growing resistance from both professionals and the broader public. With ‘Plečnik’s Ljubljana’ a main tourist attraction and the state supporting its nomination for UNESCO World Heritage status, how could the destruction of one of his major works gain official support and approval? Whatever the final decision is about building or not building the stadium, we can say for certain that the investor has already scored at least one major victory: the stadium consortium’s financial and media muscle means that the destruction of one of the central works of the most famous Slovene architect is a realistic scenario.

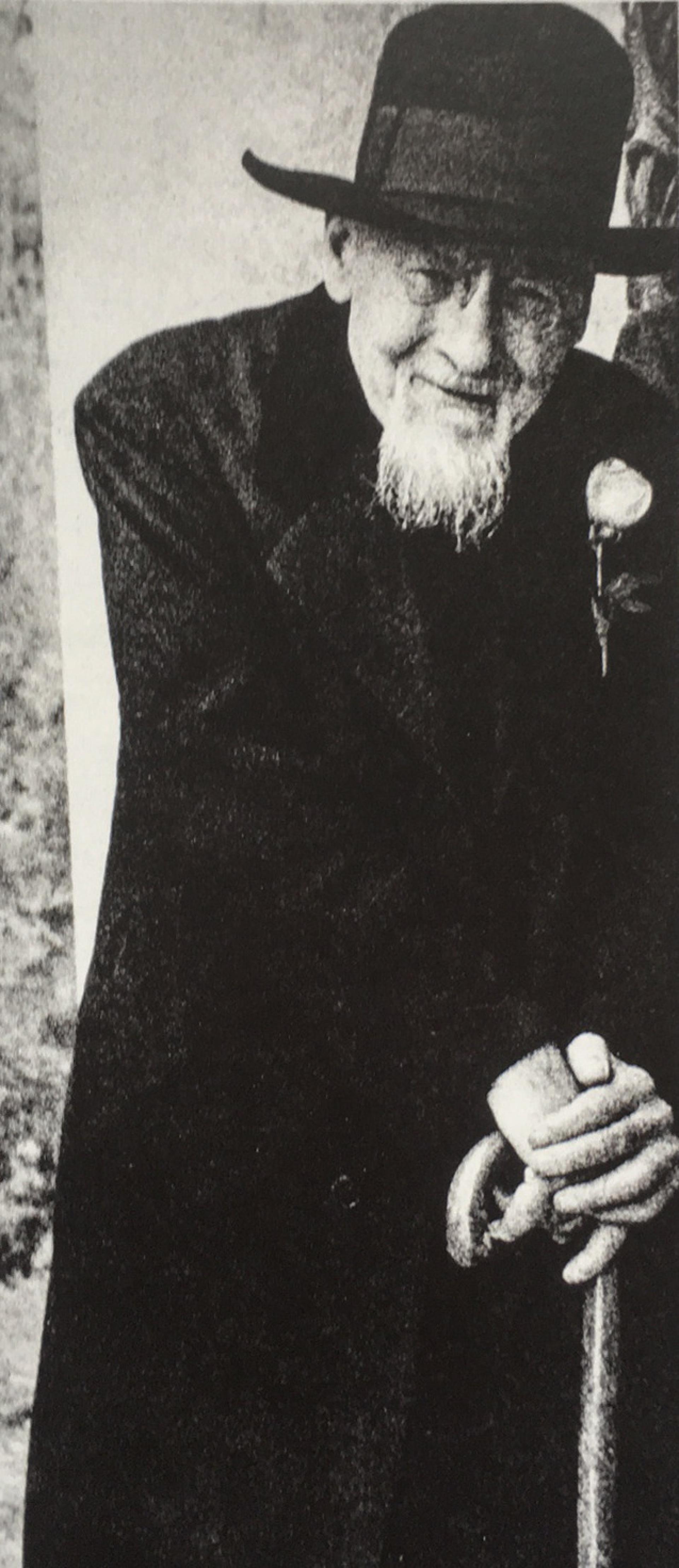

Plečnik on the Brioni Islands (1956). | Photo © Lojze Gostiša

Jože Plečnik (1872-1957) was a carpenter’s son, born in Ljubljana. In 1894, Otto Wagner, the most famous Viennese architect of the time, picked him out of a furniture design studio for his imagination and drawing skill. He soon became one of Wagner’s star pupils, and after graduation began to make his mark in the imperial capital with his avant-garde combination of modernism and classicism. A wider success followed soon after the end of the First World War, when Tomáš Masaryk, the president of the newly-created Czechoslovak republic, commissioned him to renovate the ancient Prague castle to become the official residence of the president.

At around the same time, Plečnik accepted the post of professor of architecture at the new University of Ljubljana, and began his gradual transformation of his provincial Austro-Hungarian hometown into the national capital of Slovenia. This was the beginning of Plečnik’s Ljubljana, as his idiosyncratic classicism changed both the physical fabric and the atmosphere of the city into a modern version of ancient Athens. In Plečnik’s scheme, the Bežigrad stadium by the main city avenue played a central role.

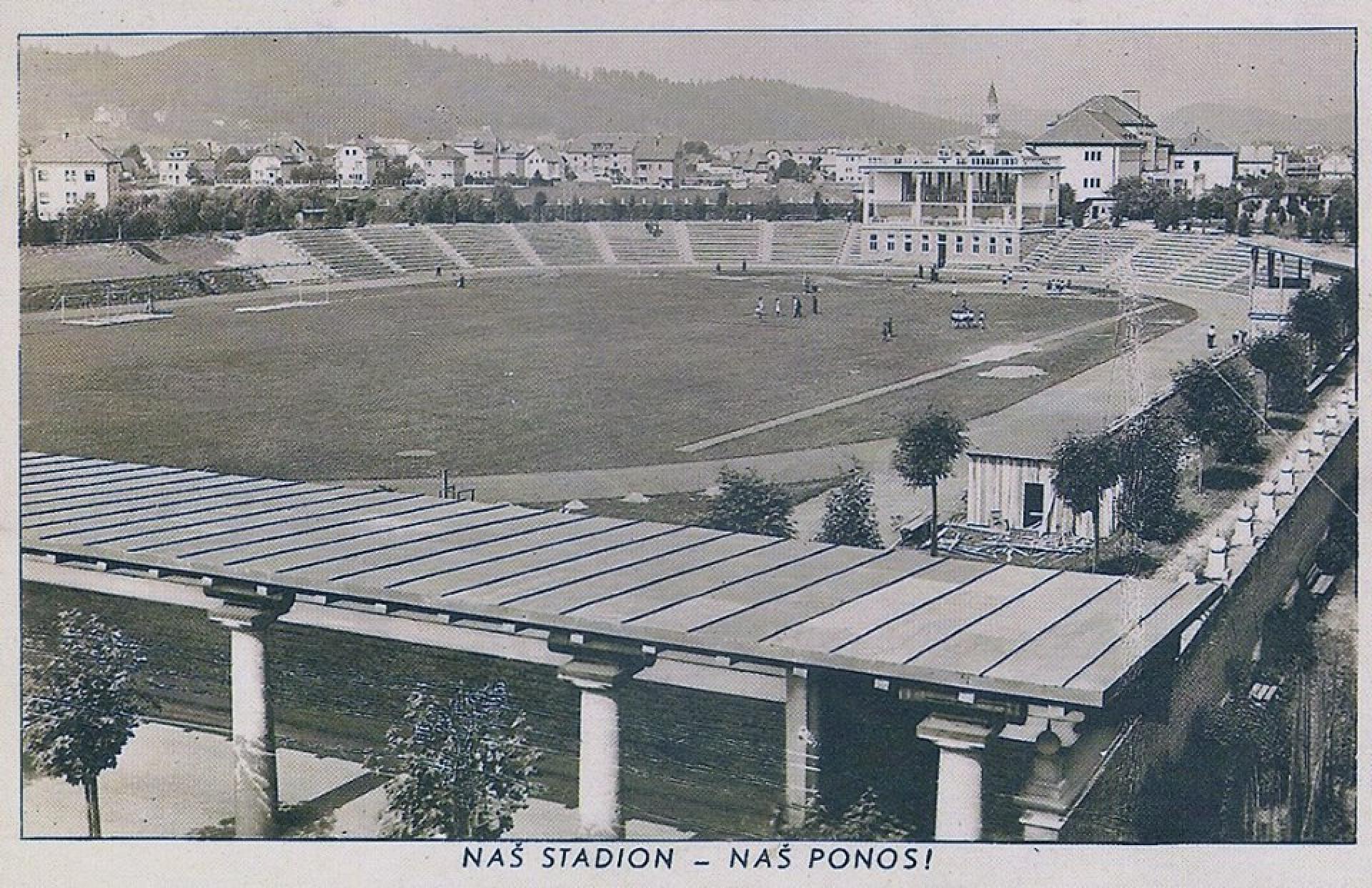

Construction of the stadium for the Roman Catholic youth sport association Orel began in 1925, but political and financial difficulties meant that it was not completed until 1935. | Photo via Outsider

The lengthy construction period and limited funds did not deter Plečnik, and one of his great strengths was his ability to improvise both materially and conceptually throughout the project.

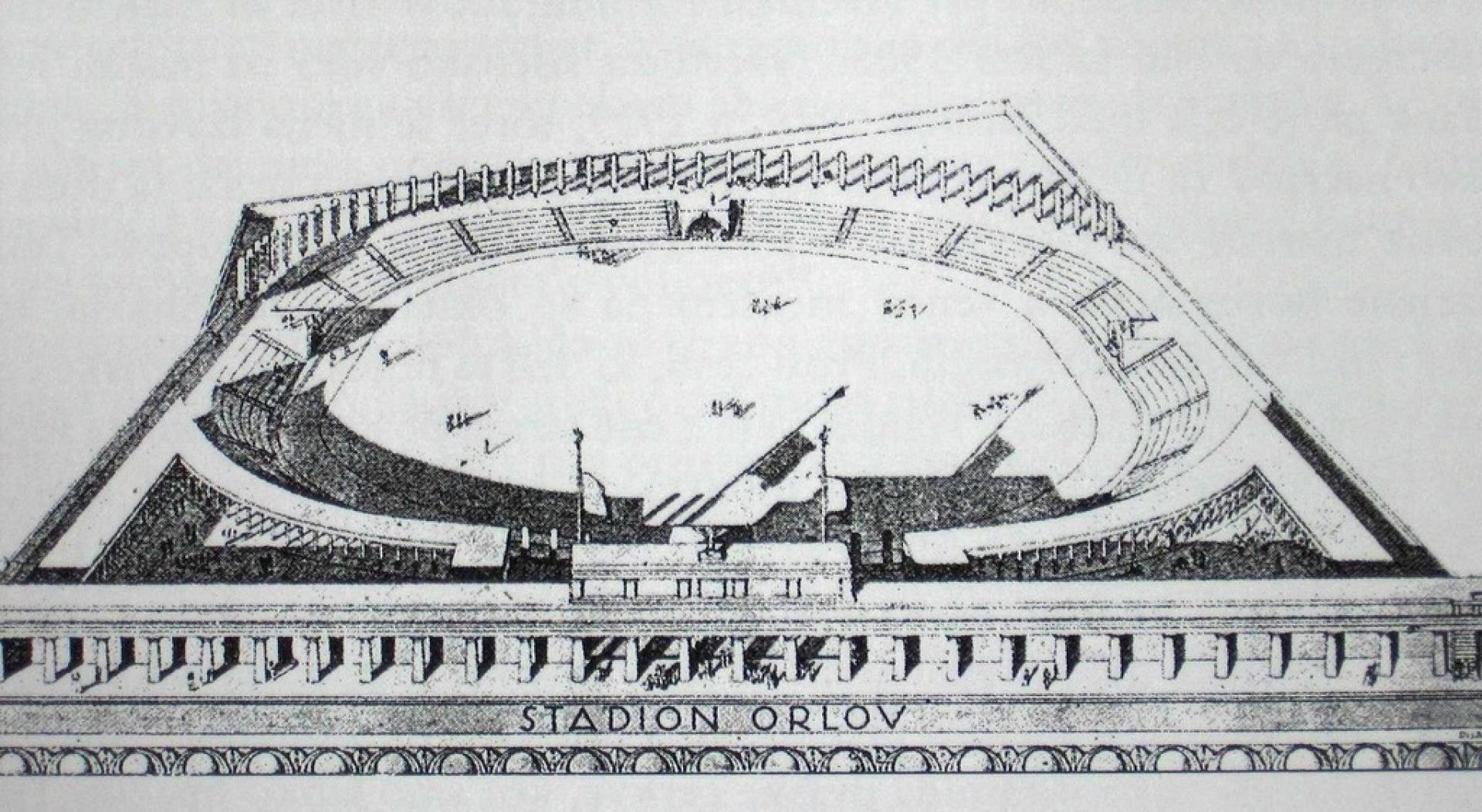

The monumental colonnade created a civic stoa or covered walkway that links the stadium enclosure with the city beyond as well as prviding for a covered space for people to queue. | Photo © Peter Krečič

At the other end is the columned ‘Glorietta’, the stadium’s grandstand, which visually dominates the low complex, rising high above the visitors’ seats. | Photo via Failed architecture

For the most part, Plečnik made use of the existing terrain, so that architecture and landscape become an inseparable unity in his vision of the new space. The tree-lined avenues at the edges provide a visual accent of the enclosure, while the ingeniously-designed low brick walls divide the auditorium from the rest of the city, allowing a gradual transition from the wide and busy road on the one side to the low-level single-family houses with gardens on the other.

The communal gardens of the nearby Fond Blocks represent a sustainable and community-driven space at the northern edge of the complex, which has survived since the 1930s. | Photo via Failed architecture

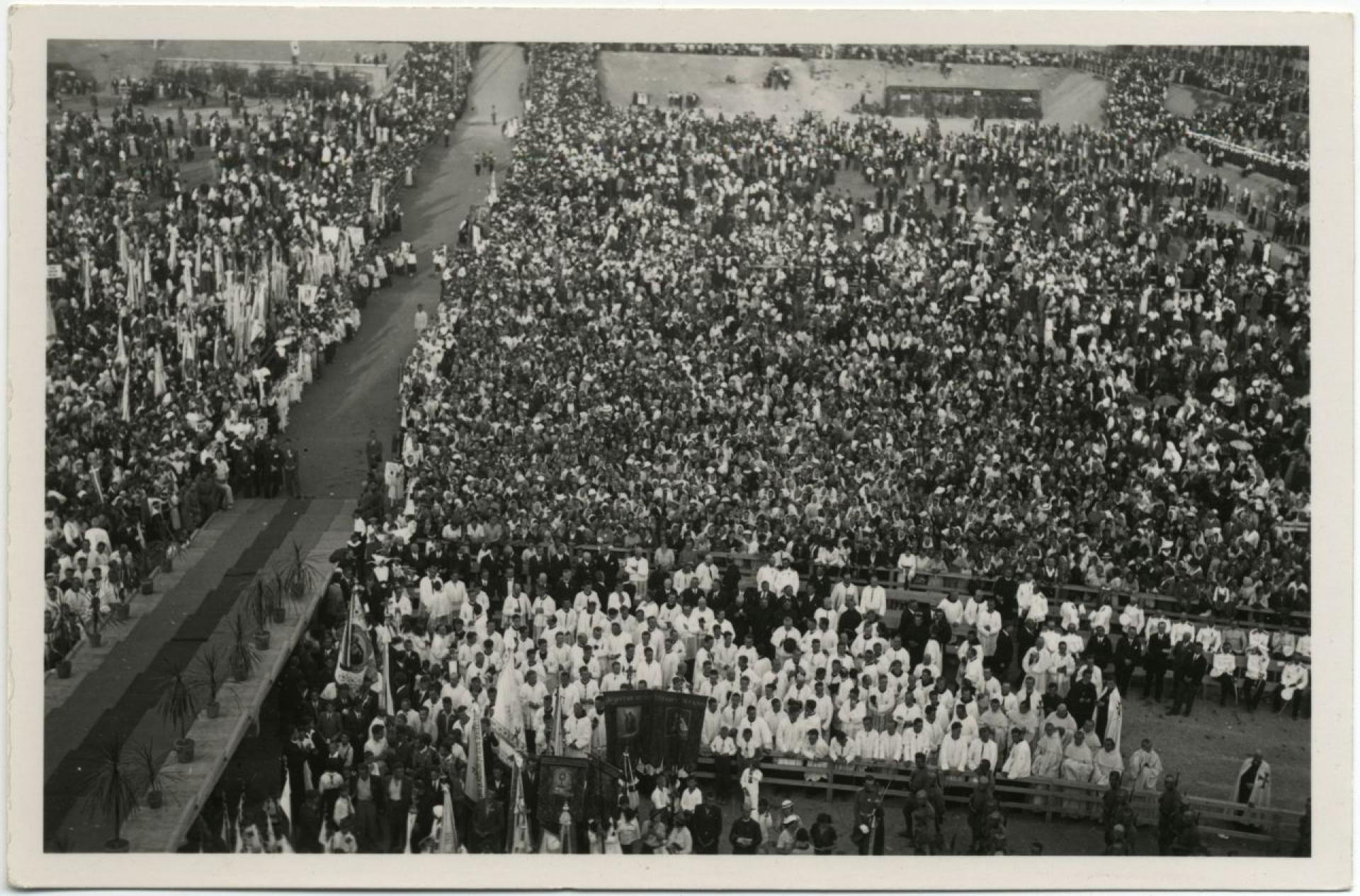

The stadium became one of the central venues for landmark sport, music and political events in the history of the city and of the country. Later, it was converted into a football stadium, but its design and infrastructure were not ideal for this purpose. In 2010, a new football stadium was opened next to the the city motorway ring, and the old Plečnik stadium was closed.

Different events during the history, also the first Eucharistic Congress in 1935 among them. | Photos via Nonument

It was at this point that the campaign for the radical reconstruction of the area began. In 2008 a public-private consortium led by Pečečnik and the Municipality called for an international competition, which was won by the GMP Architectural office from Berlin. The architects proposed extensive new construction to ‘optimise’ the commercial return on the extremely valuable plot. Almost all of the buildings would be torn down, with the site excavated to a depth of 22m and built up with basements of car parks and sport halls on five levels. Above the ground, a new stadium, with covered seating and VIP boxes on three levels, would be built, while around the outer edges of the new stadium, there would be an 18-storey skyscraper and three apartment blocks on the site of the communal gardens. Almost all of the Plečnik Stadium (except for the Glorietta and the colonnade) would have to be demolished.

The stadium in the 1950s and today, overgrown by vegetation. | Photo © Edi Šelhaus, Failed architecture

As a compromise, the investor has promised to rebuild the wall around the perimeter of the plot to the original plans and provide for the visitor stands where the old auditoriums were situated. Despite the almost total destruction of the stadium, the project has consistently been branded as the preservation of Plečnik’s legacy, reinforced by the fact that the stadium – now in the ownership of the stadium consortium – has been decaying ever since its closure. Redevelopment is, the investor claims, the only way to save the stadium, at an estimated cost of 240 million Euros while providing 800 new jobs.

Proposed reconstruction. | Rendering by GMP Architekten

Pressure from political and private interests has led to the project gaining widespread official approval, including that of the Heritage Protection Agency. This raised many eyebrows, as the Plečnik stadium was awarded the highest possible protection status of 'Heritage of National Importance’ in 2010 (of course, the stadium is not part of the UNESCO nomination, because of its present status and uncertain future). The independent civic society and professional architectural, heritage and art-historical societies are all united in their opposition to the destructive plans. The international limelight was added to the redevelopment plans by the inclusion of the Stadium on the list of 7 most endangered European cultural heritage sites in 2020 by the NGO Europa Nostra. All of these organizations argue that redevelopment in this case means destruction only, with less than five per cent of the stadium preserved, while building up the whole of the plot would destroy not only the physical substance of Plečnik’s masterpiece but also the spatial totality of the public, urban recreational facility the stadium has always been. Ljubljana’s many unfinished construction sites raise further concern; economic uncertainty could mean that the consortium would have enough money to destroy a heritage site, but not to bring its plans to fruition. The new facility also seems unnecessarily ambitious, as a new stadium in Stožice meeting international standards is already built and operating well, and Ljubljana, a city of 300,000, has no need for two state-of-the-art football stadiums. The plans for the public part of the complex could be just a way of convincing stakeholders to sanction the destruction of heritage, with the end-product even less public and more commercial.

No one from the Municipality or the state will admit that the choice between the slow decay of the stadium and rapid destructive redevelopment is a false one. According to the esimates by the Ministry of Culture the third option, a faithful renovation of the complex as a civic recreation and sports park, would cost just around 3 million euros (1 per cent of the BSP project estimate). Such a low renovation estimate is possible because of a simple and economic conception of the original stadium, a consistent feature of Plečnik’s architecture in general. Ljubljana, a much richer and better-educated city than it was in 1935, seems to have lost the qualities of the great architect that gave it its shape.

– Miloš Kosec

This article was first published in C20, the magazine of the C20 Society. See for more information join C20society.