FOMA 45: International Style, Structure And Space

Guillermo Dürig selected five projects for this month’s FOMA. Cases are part of the International Style in North America and Europe, which share modernist principles of volume, regularity and flexibility. Their large-scale structures offer various solutions for public programs creating new spatial typologies and constructive synergies while transcending the classic disciplines of architecture and engineering with specific and unique solutions.

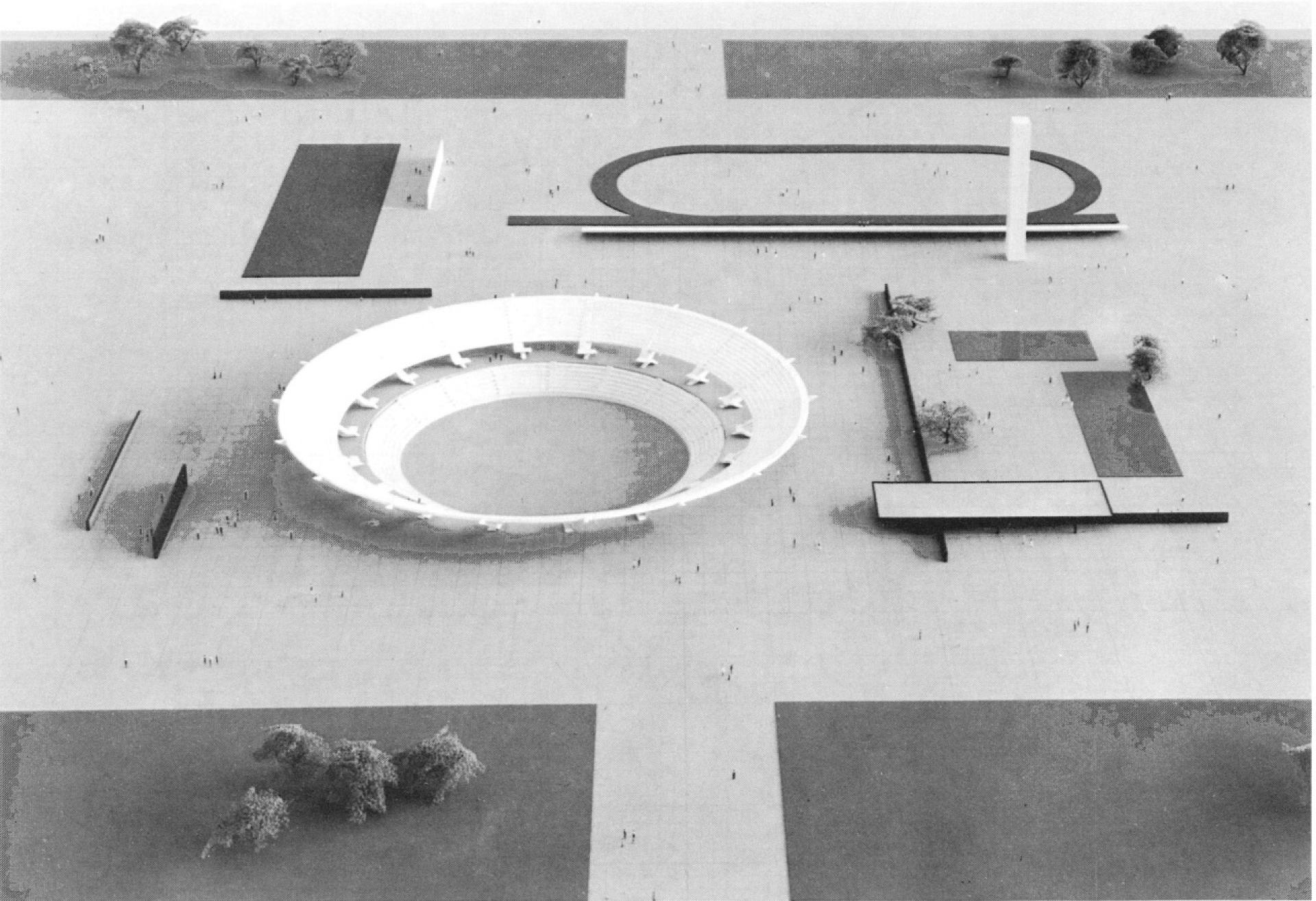

Morphological implementation of the large - scale structure in the context of the city. | Collage MvdR office, © MoMA, New York, scanned from: Phyllis Lambert, Mies van der Rohe in America, Montréal and New York 2001, p. 462.

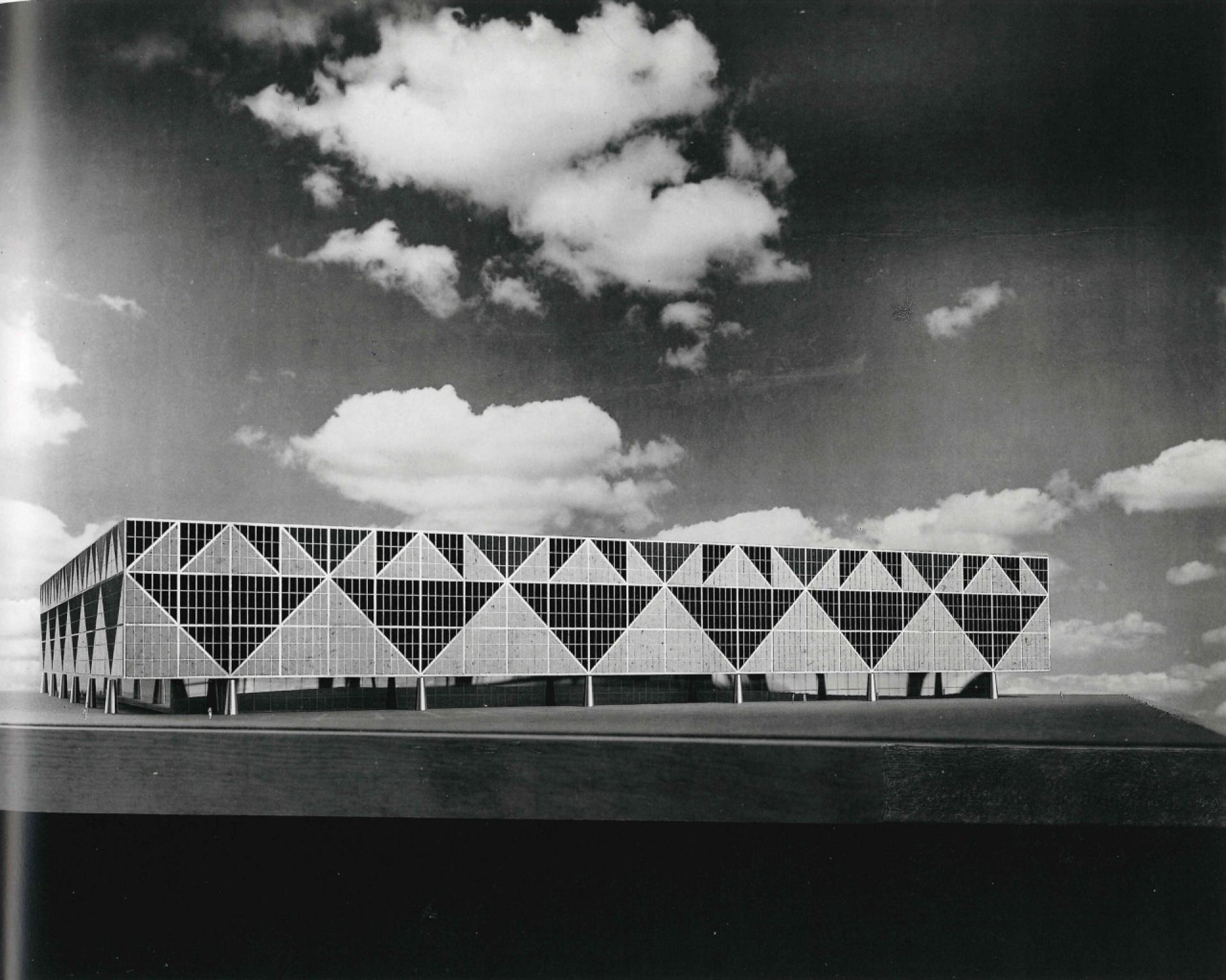

The two-tone aluminium panels make the structure of the Chicago Convention Hall Project. | Model MvdR office, © MoMA, New York, scanned from: Phyllis Lambert, Mies van der Rohe in America, p. 473.

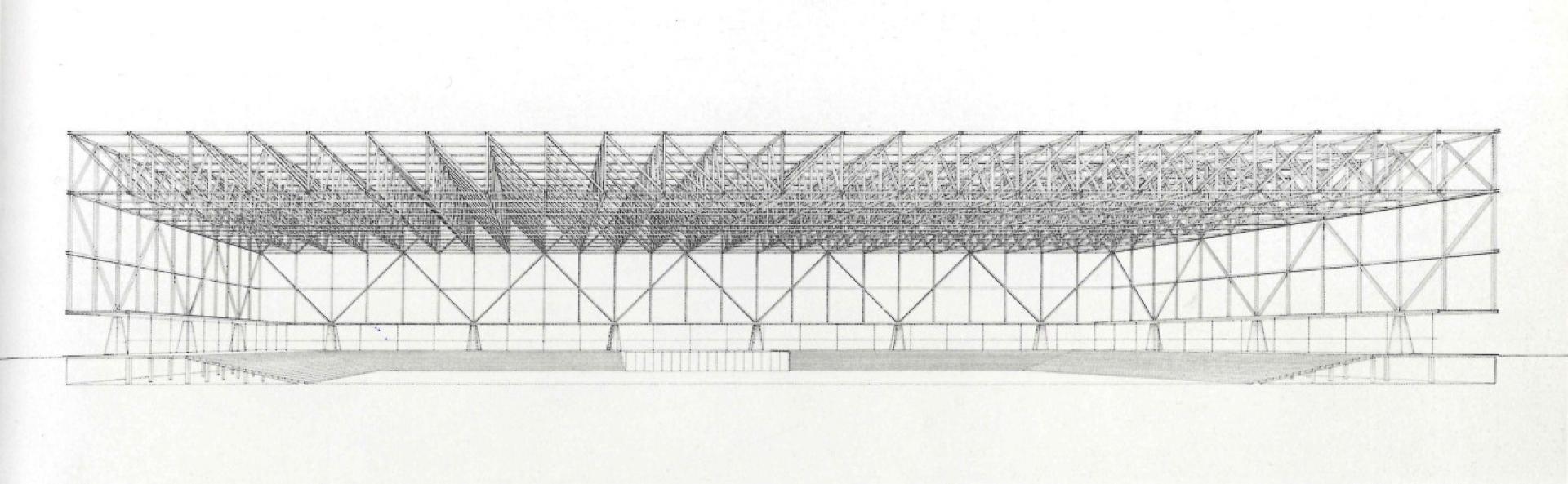

The entire hall of the Chicago Convention Hall Project rests on the peripheral pillars. | Drawing MvdR office, © MoMA, New York, scanned from: Phyllis Lambert, Mies van der Rohe in America, p. 467.

Mies van der Rohe created his Chicago Convention Hall Project (1953-54) in which the clear-span roof shelter of 219,45x219,45 m creates a polyvalent hall defining a universal space able to host 50’000 seated people and a sports arena or an exhibition space. The exposed structure is engineered as a non-hierarchical two-way truss system resting on punctual supports, aiming for greatest purity following Mies’ ideal: “Construction not only determines form but is form itself.” [1] The composition of the façade is directly derived from the trusses and cladded with different tonalities of insulated aluminium panels, making its constructive logic of the buildings main expression. The hall itself, as the largest of four buildings, sits in the centre of a plane field, flanked by smaller box-shaped volumes in a typical Miesian composition. There is no need for spatial or morphological mediation to the surrounding city as stated by Mies: “A Hall of this dimension doesn’t depend on its environment: it creates its environment.”[2]

The second case is a student Master Thesis by Emmanuel Glyniadakis, entitled A sports centre (1964) under the supervision of Myron Goldsmith, Fazlur Kahn and Davis Sharpe. A minimal structure defines the space for an arena, a track with field area, a swimming pool and a flexible area for diverse sporting activities under an 810-foot-square (246,88x246,88 m) roof.

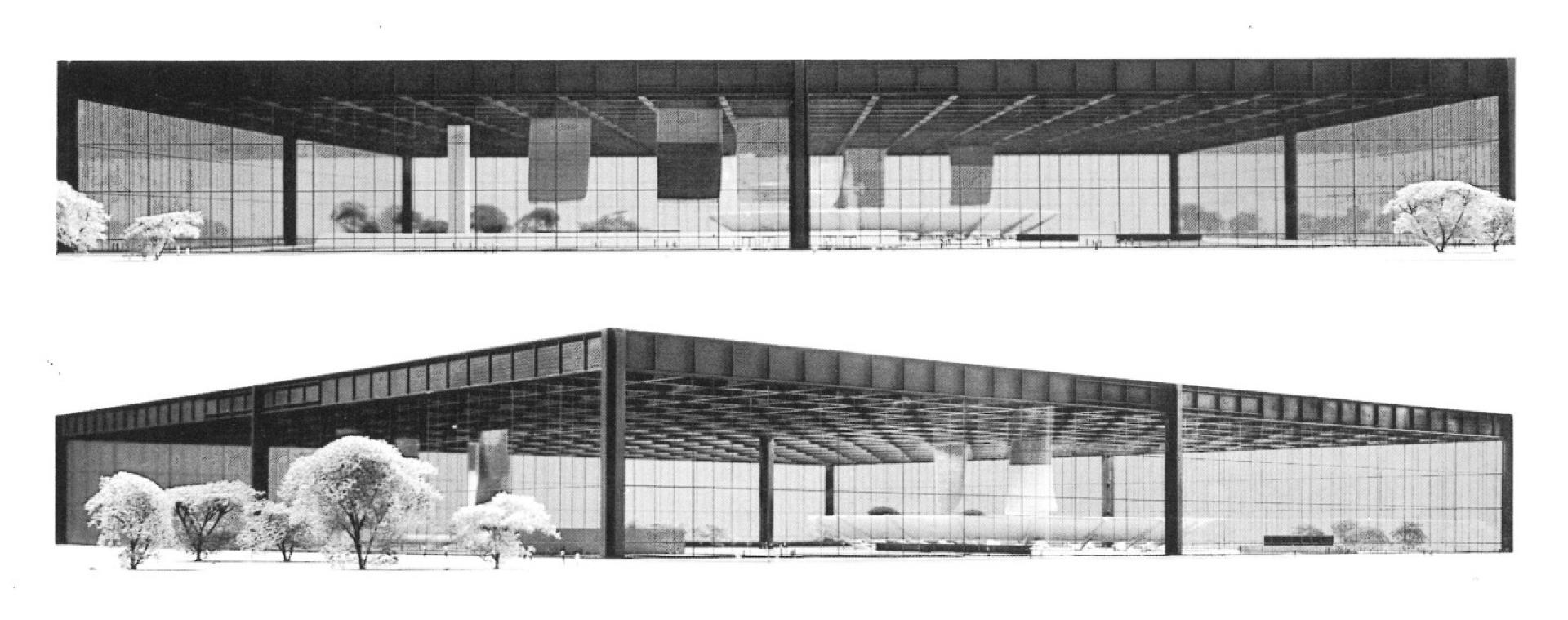

A minimalistic architecture shelters various functions. | Photo © Charles Reynolds, scanned from: Myron Goldsmith; Werner Blaser (Ed.), Buildings and Concepts, New York 1987, p. 153.

Functions as detached elements on a plane grid. | Photo © Charles Reynolds, scanned from: Werner Blaser (Ed.), Buildings and Concepts, p. 152.

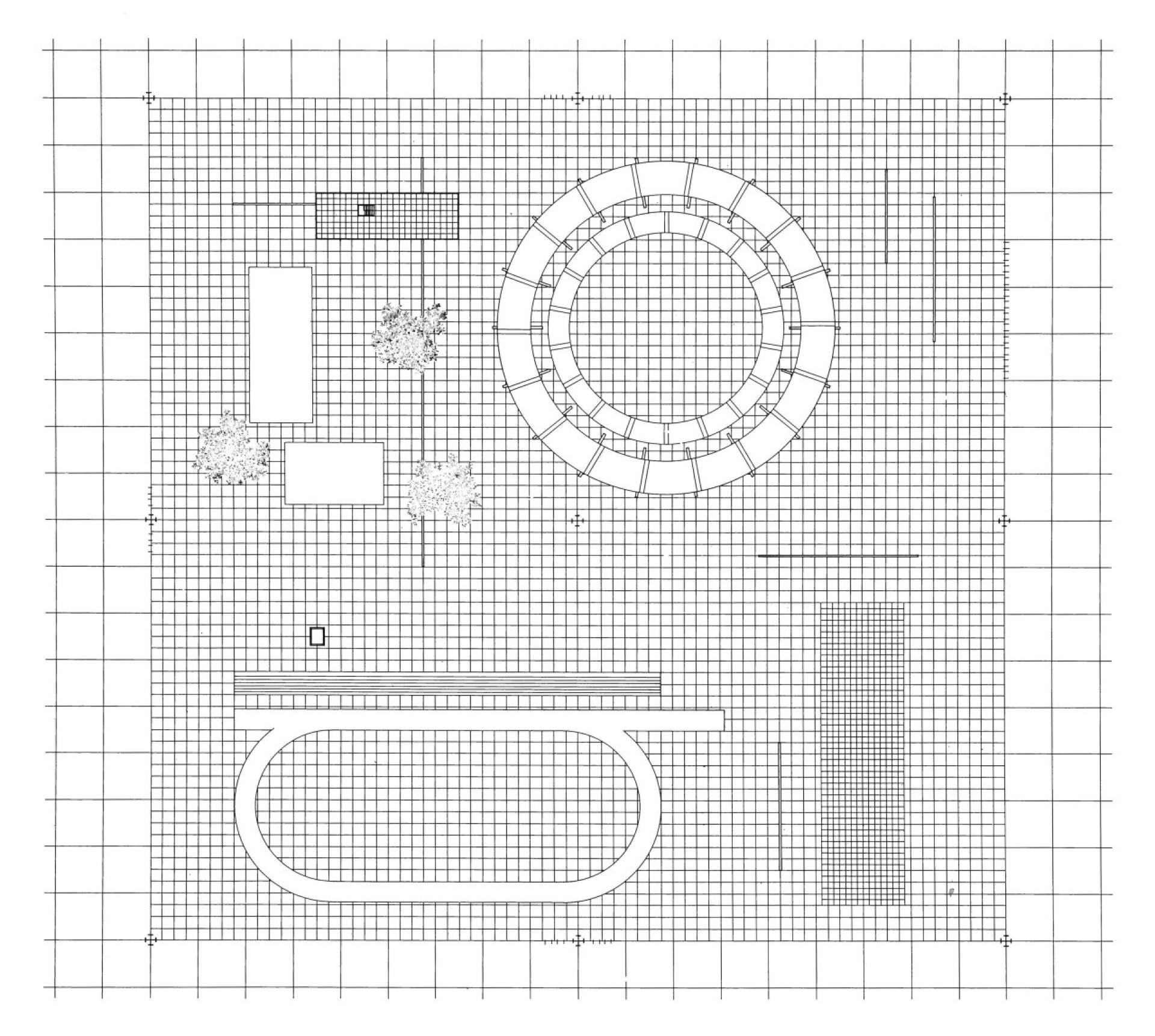

Ground level with different sports arenas in the open space. | Plan © Emmanuel Glyniadakis, from: Werner Blaser (Ed.), Buildings and Concepts, p. 151.

The steel structure consists of a two-way grid with a height of 5,18 m and rests on nine pillars. While the grandstands in the convention hall are sunk into the ground, the project arranges the different elements like furniture objects on a plane field, creating a formal composition. A glazed wall along the roof’s periphery seamlessly shelters the program with the public space expanding as a continuous grid from the inside to the outside. The project’s architectural expression is characterised by the minimal and consequent expression of the structure and its programmatic infills.

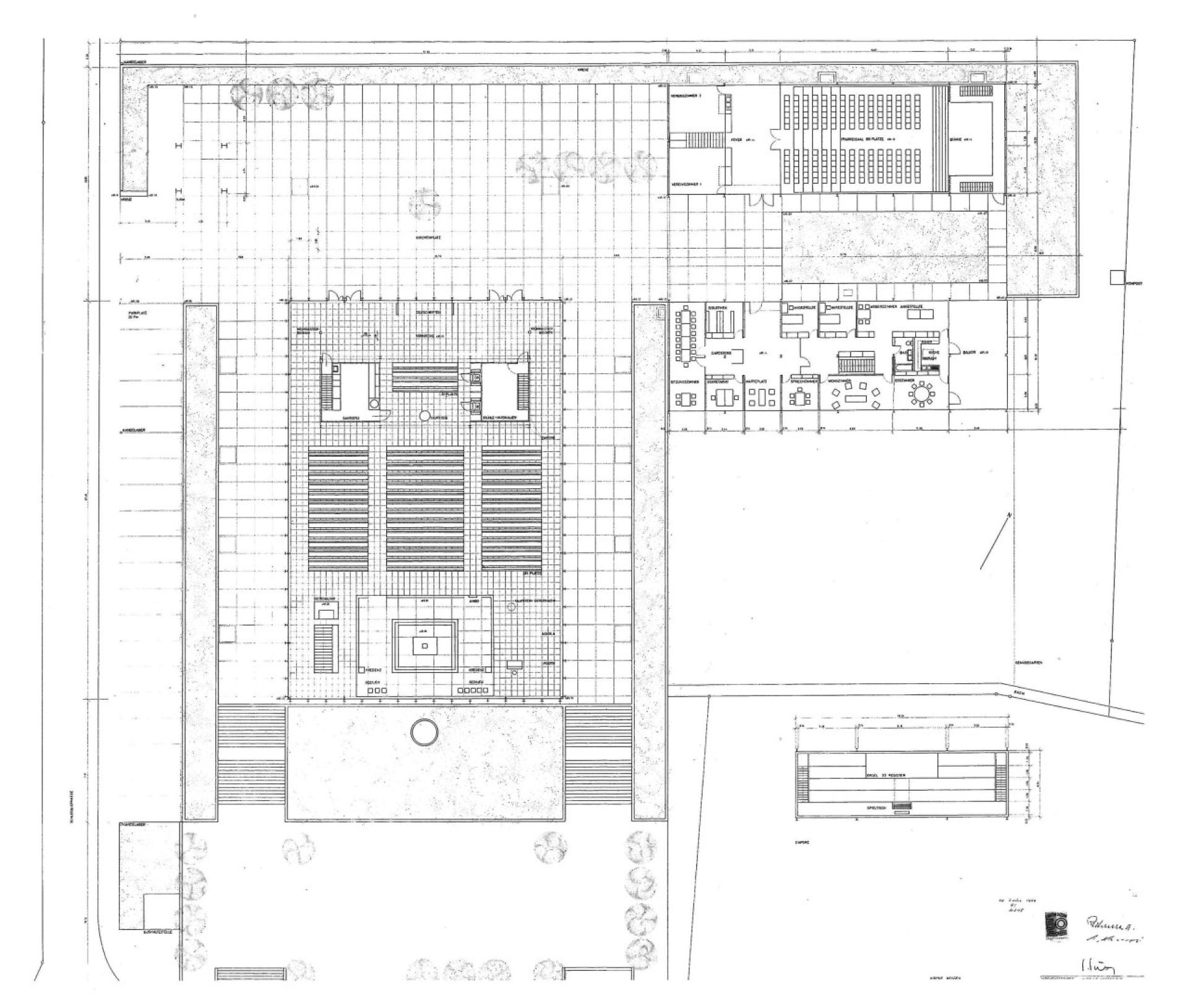

Franz Füeg has created a grid based on the dimension of 1,68 m served as basis for the church’s strict modularity and final dimensions of 37,3m by 25,6m. The facade of the St. Pius Church in Meggen (Switzerland) consists of steel profiles, which don’t only hold the marble panels in place, but also support the main structure made out of filigree and custom-made trusses.

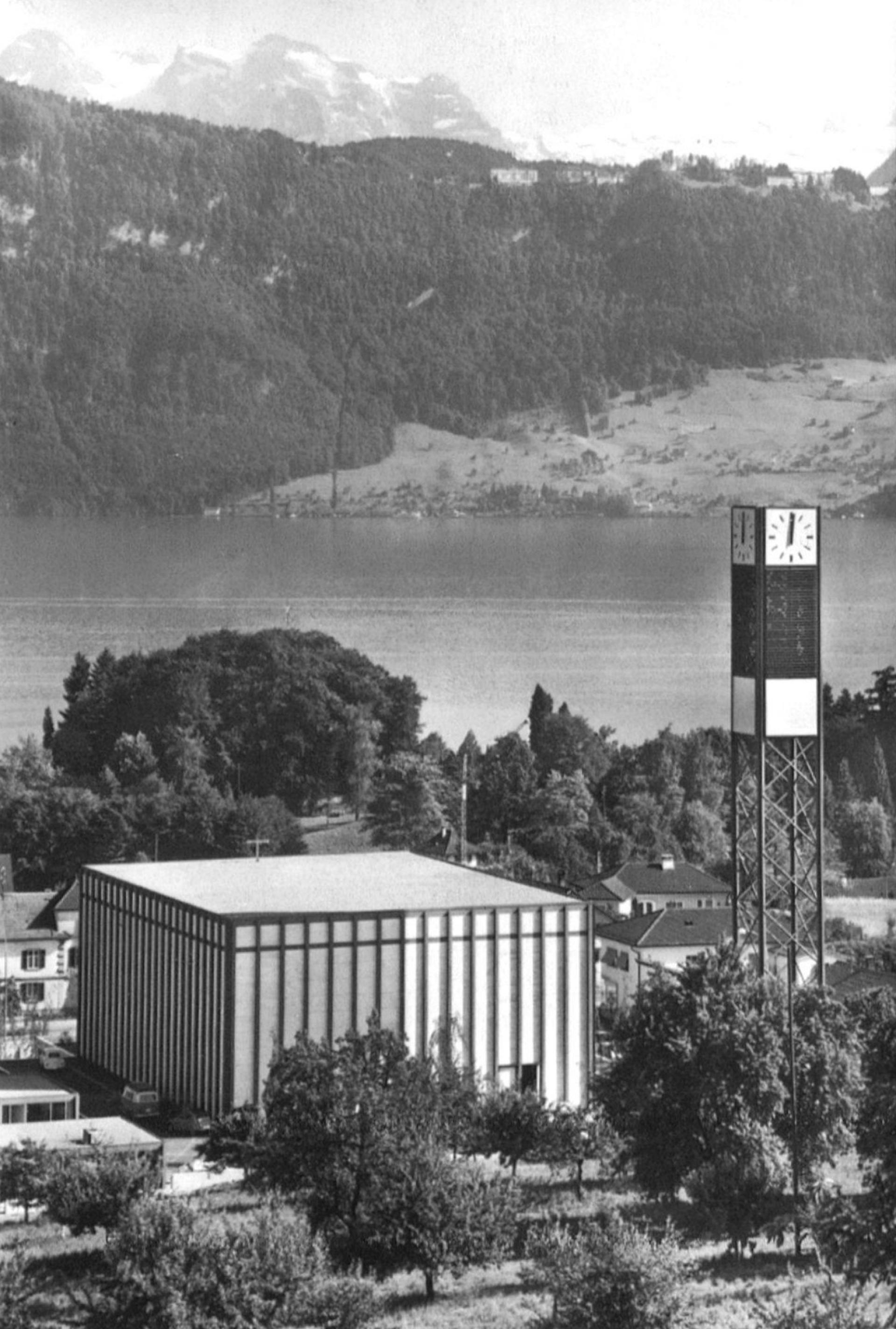

Overview over the church, the bell tower and adjacent buildings for the parish (left). | Photo: Archives de la construction moderne (ACM), EPF Lausanne, taken from: Kunst + Architektur in der Schweiz, 56, 2005, p. 56.

The 28mm thick Pantelikom marble from Athens filters the daylight and illuminates the space evenly. | Photo © Archives de la construction moderne (ACM), EPF Lausanne, from: Kunst + Architektur in der Schweiz, 2005, p. 57.

Diagonal wind bracings in the four corners stabilize the structure. The sloping topography of the site exposes a concrete base acting as a precise and sober volume for the lightweight church to sit on. The industrial use of steel as well as the project’s modularity bases on what Füeg had conceptually described as “start building a church as if it would be a factory.” [3]

The floor plan of the church and its repetitive grid. | Scanned from: Jürg Graser, Gefüllte Leere, Zürich 2014, p. 217.

The translucent marble panels shine outward during the night and light the hall subtly during daytime, creating a volume of light. The non-industrial trusses excluded, the constructive excellence, the rigorous execution of the details as well as the exposed structure are consciously derived from Mies’ idea of the symbiosis of architecture and construction.

A weightless roof hovering above a glass volume. | Photo © Arne Jacobsen, Royal Academy of Fine Arts Library, collection architectural drawings, scanned from: Carsten Thau, Kjeld Vindum, Arne Jacobsen, Copenhagen 2001, p.454

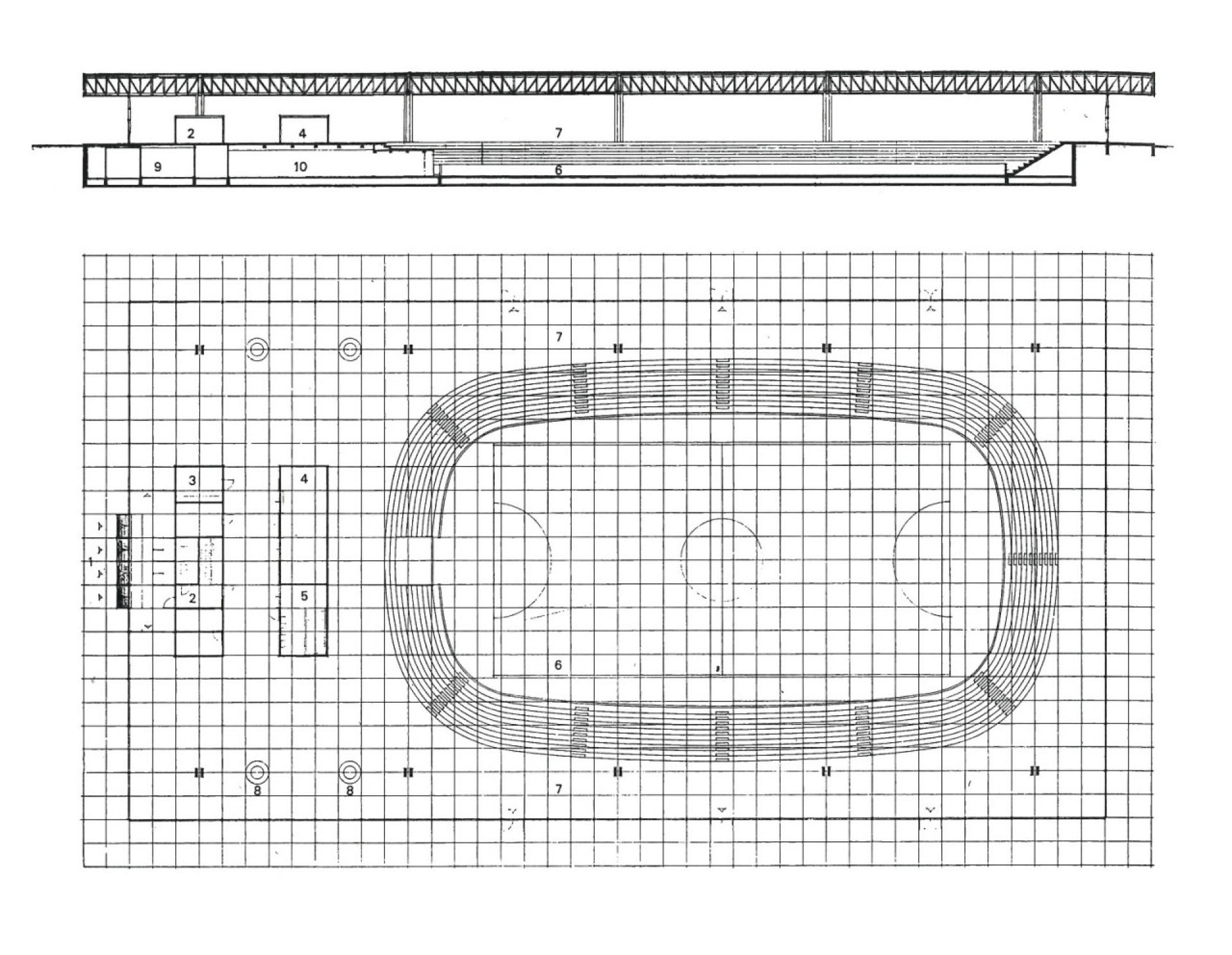

The Sports hall for the City of Landskrona (Sweden) by Arne Jabcobsen consists of a rectangular roof of 52x92 m, a podium elevated 20 cm over the ground and a transparent glass wall in-between. In order to remove every vertical sensation and reinforce the horizontal character, the columns are shifted to the inside of the hall and split in two.

The ball field and the bleachers as depression in the plinth. | © Dissing + Weitling’s archives, from: Carsten Thau, Kjeld Vindum, Arne Jacobsen, p.457.

In order to remove every vertical sensation and reinforce the horizontal character, the columns are shifted to the inside of the hall and split in two. The structure and the technical installations are hidden above a suspended ceiling, turning the roof into an abstract apparatus, breaking with Mies’ ideology of the structure as the main space defining element. The focus shifts from the construction to the volume. [4]

Like furniture elements, two wooden boxes stand inside the open space. | © Arne Jacobsen, from: Carsten Thau, Kjeld Vindum, Arne Jacobsen, p.454.

A ball field with its bleachers is sunk into the podium, two wooden pavilions house ancillary rooms. The wardrobes as well as the technical areas are inside the podium. While the architectural language and spatial organization still roots in the International Style, a new facet emerges as the expression shifts to “[…] a dematerialized architecture, an architecture without gravity. The dream of a hovering plane” as described by Thau and Vindum.[5]

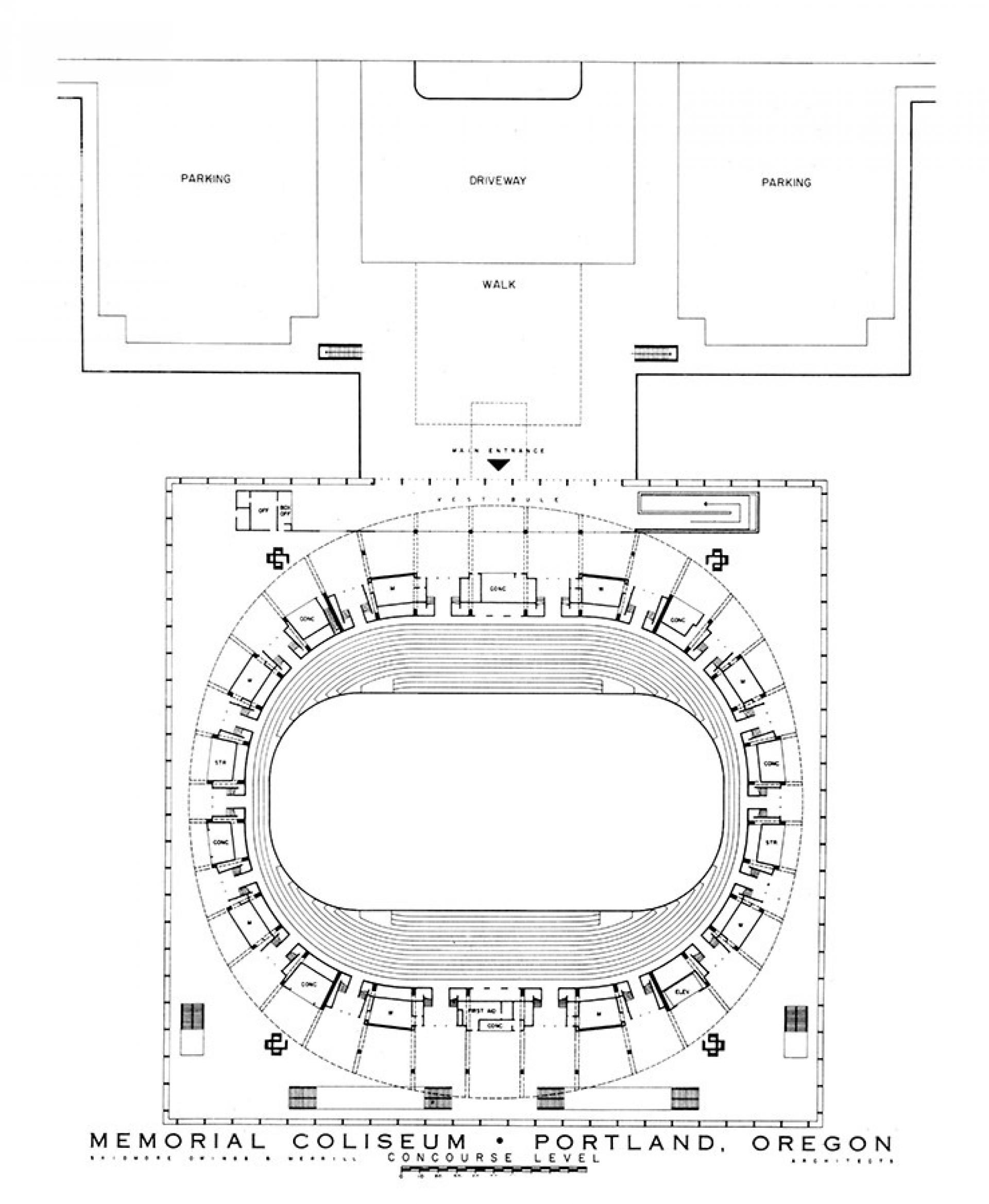

The freestanding, multifunctional concrete oval bowl of the The Memorial Coliseum’s sports arena is wrapped in a 360-foot-square (109,72x109,72m) box. The four reinforced concrete columns are shifted into the inside and are totally independent from the arenas’ structure as well as the façade, offering a clear height of 10,97m.

Filigree pavilion resting on an elevated plinth. | Photo © Julius Shulman, SOM

Cantilevered steel trusses are optimised in height and width according to the spans and hidden together with the technical ducts above a false ceiling following Jacobsen’s strategy of prioritising the space itself.

Circulation space between stadium and façade. | Photo © Art Hupy

While the spectators access the stadium from the parking lot through the glazed public area surrounding the oval, a plinth containing the restricted program is introduced.

Access level of the spectators. | Plan © SOM

Being surrounded by a new artificial embankment, the glass pavilion appears to hover over the terrain. Staff and athletes access it through precise incisions in the ascending slope. The minimal architectural expression is characterized by the conceptual tour de force between the abstractness of the shell and its sculptural content.

Notes:

- Mies van der Rohe, lecture, Chicago occasion and date unknown, quoted after: Fritz Neumeyer, Mies van der Rohe on the Building Art. The Artless Word, Cambridge 1991, p. 325.

- Mies van der Rohe, undated typescript, probably prior to 11 November 1953, quoted after Phyllis Lambert, Mies van der Rohe in America, Montréal and New York 2001, p. 463.

- Franz Füeg, Gedanken zum Kirchenbau, in: Bauen + Wohnen, 1958, 11, pp. 294-296. Quote translated by the author

- On this shift see: Carsten Thau, Kjeld Vindum, Arne Jacobsen, Copenhagen 2001, p. 456.

- Carsten Thau, Kjeld Vindum, Arne Jacobsen, p. 458.

Guillermo would like to thank Joshua Brägger and Philipp Krauer.

Guillermo Dürig is a swiss architect based in Zurich. He graduated from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH) obtaining his diploma in 2013. After interning at Juan Navarro Baldeweg in Madrid in the years 2009-10, Guillermo joined Jean-Pierre Dürig’s practice in 2013 and becoming the head of DÜRIG AG in 2021. The main interest of the office lies in the development of radical and conceptual projects, as well as in the execution of public buildings and large-scale infrastructures. In 2015 Guillermo co-organized the summer school ‘MAU’ in Motovun (Croatia). From 2016-19 he worked as a teaching assistant at the chair of Marc Angélil at the ETH, being in charge of organization of the semester on Madrid and Porto. Additionally, he has been a guest critic at the ETH as well as at the ZHAW. His works have been featured and exhibited in various specialized media.