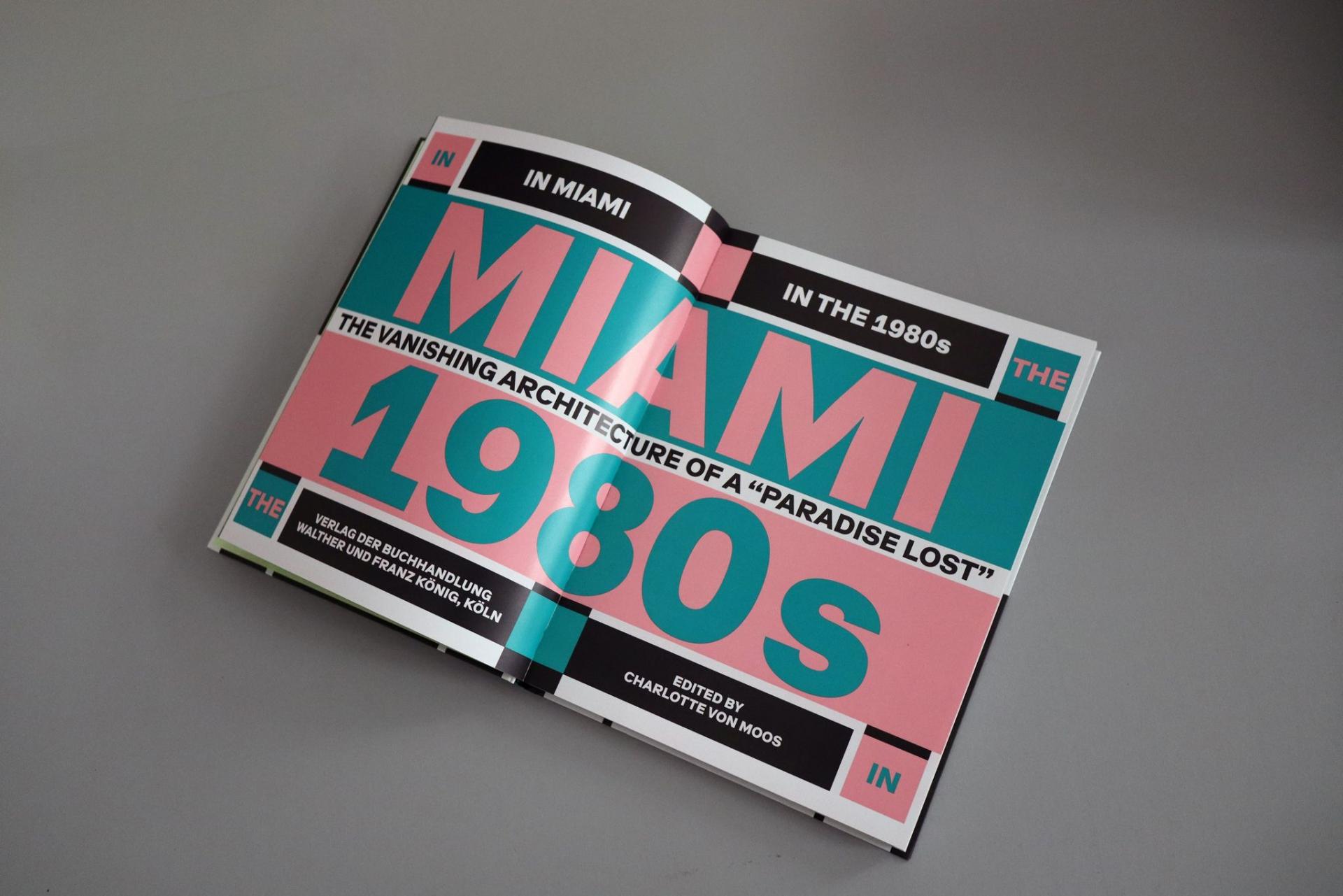

Charlotte von Moos (ed.): Miami In The 1980s

Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König, Köln, 2022

First things first: that book is cool. The graphic design, in mint green and dusty pink is clearly an homage to its subject – the architecture from postmodern Miami. But not only it respects on glossy paper the colour code of an era and style, it’s full of new drawings (plans and façades) that allow us to understand buildings we knew as images in depth and to consider their architectural qualities. As it must be the book starts with screenshots from the main title of the TV-Series Miami Vice (1984-89) that reminds us that – for the first time in history – architecture had become a real protagonist in storytelling. Remember: two undercover cops dressed in Hugo Boss suits hang around Miami driving a white Ferrari Testarossa, they pretend to be drug dealers to catch the bad guys enjoying the sun of Florida. This criminal society meets and lives in houses that fit their lifestyle and the neo-modern villas from Arquitectonica are not only the decor of their life – they tell us about the taste, the habits and the dangers from those people. Michael Mann was the creator and executive producer from that series and if you’ve seen any other of his films you’ll know one thing: he loves the visual power of architecture and understands the role it can play in storytelling (so was Alfred Hitchcock's review).

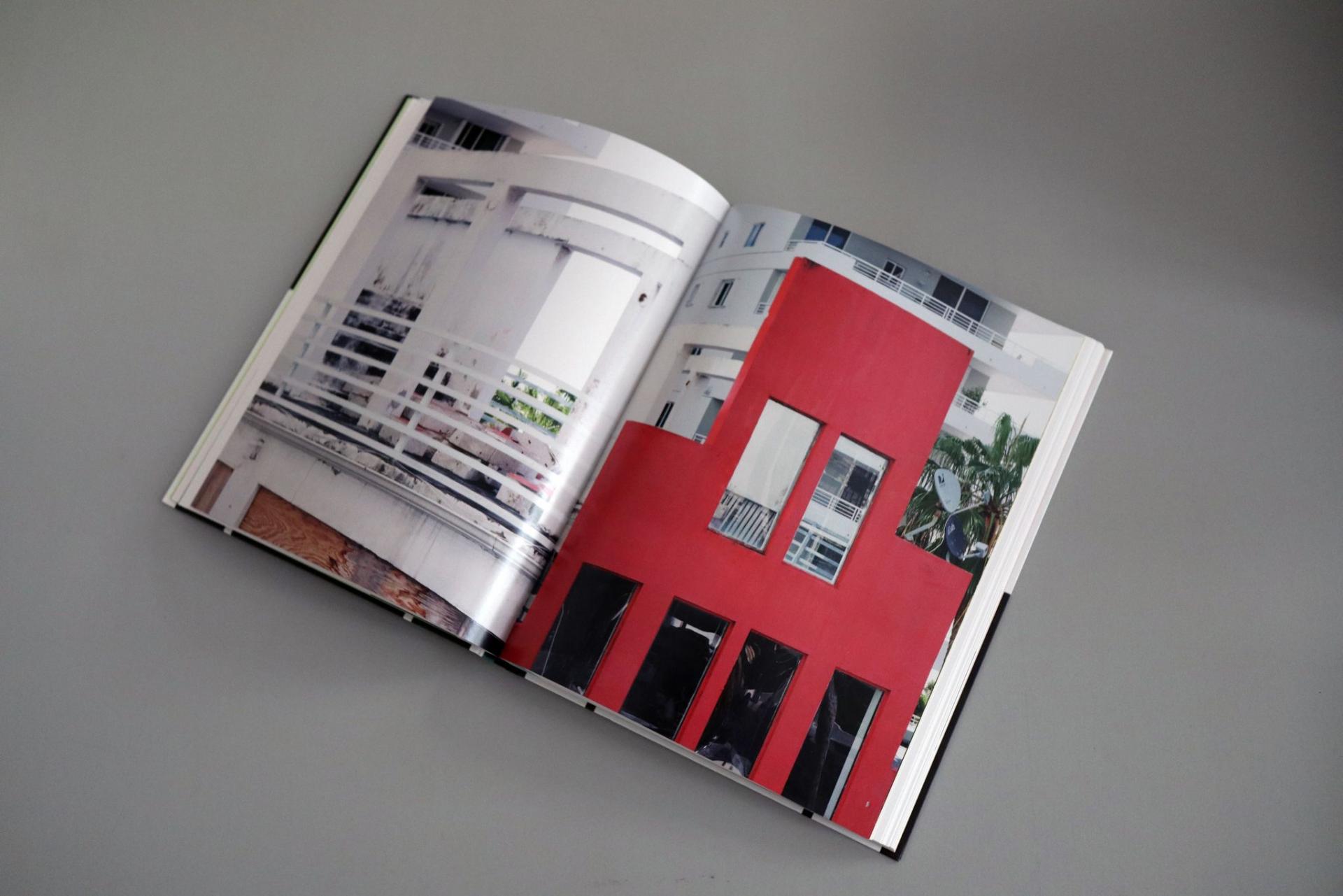

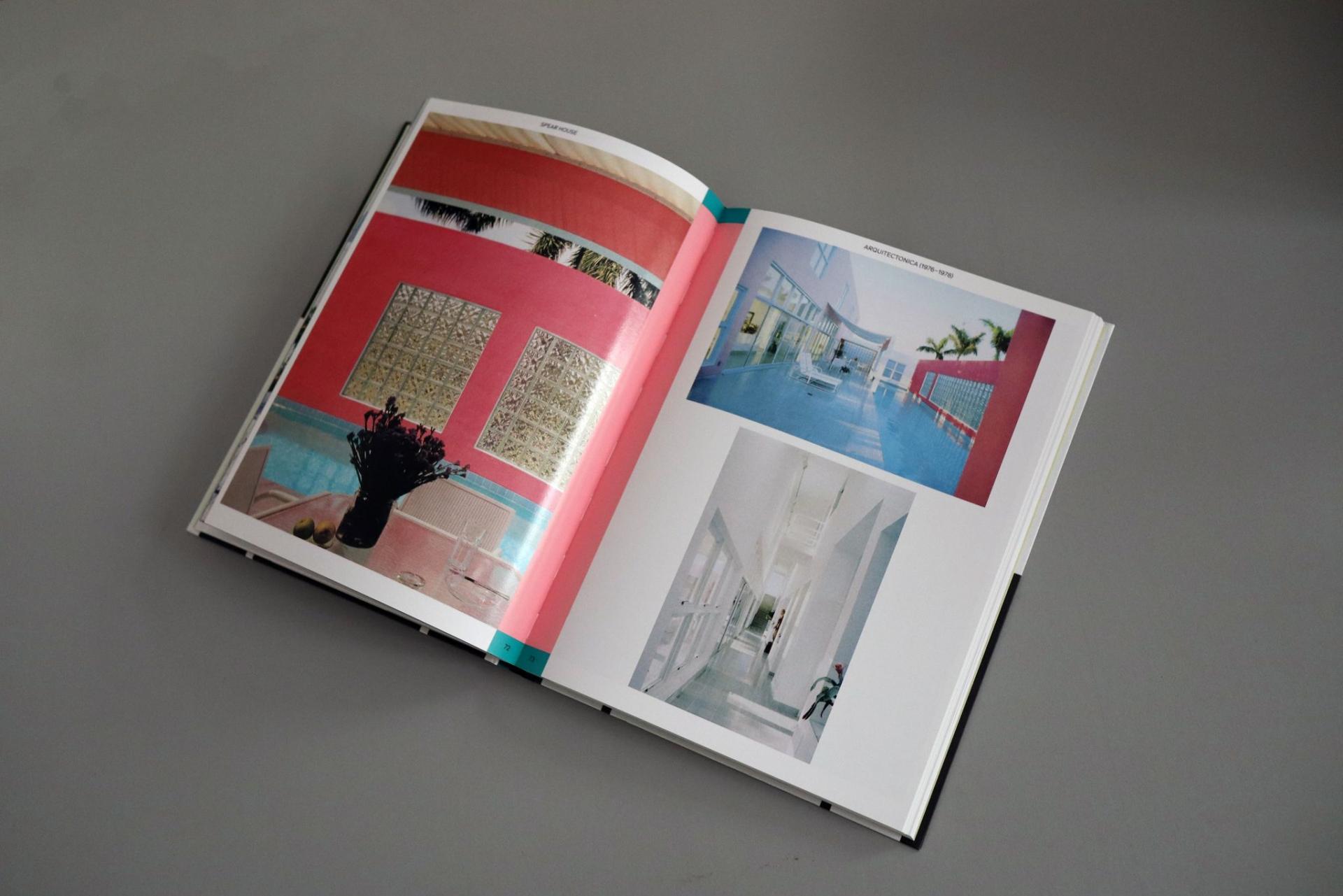

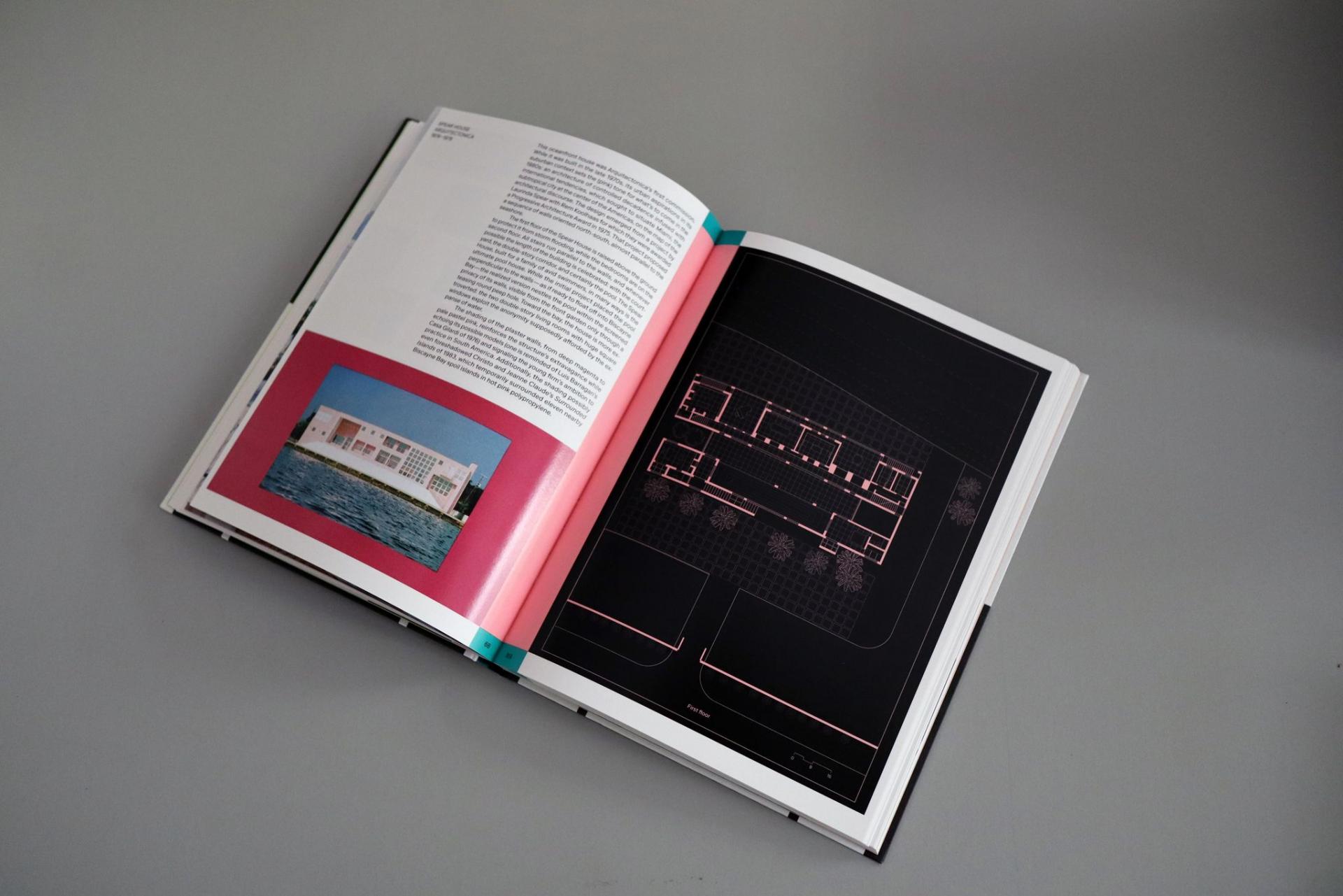

Many of us know the images from Miami Vice and if, like me, you were born in the early 1970s and watched too much TV – you looked at them as an adolescent and became an architect because of them. I did. But the genius of the book is to reveal us the context, the ideas and concepts that were around at that time and who brought a generation of architects to the invention of a very unique and local style. For sure, as post-moderns, they wanted to play with history, to mix Adolf Loos or Le Corbusier with ornamented porticos à la Aldo Rossi (the buildings of Duany Plater-Zyberk are a perfect example from this approach). But one should not forget that the iconic Spear House (1976-78) was the child of a project developed by Laurinda Spear and Remment (not yet Rem) Koolhaas in 1974, at the peak of his obsessions with Surrealism, Constructivism and the Berlin Wall. Last but not least, they all understood the power of colour and refused the dogmatic boredom of white plaster. The essay from Charlotte von Moos unfolds all those references, brings unknown archives to life and fascinates with its enthusiasm. The whole book makes it clear: those buildings were not just a set for TV-series but true architecture with its successes and mistakes.

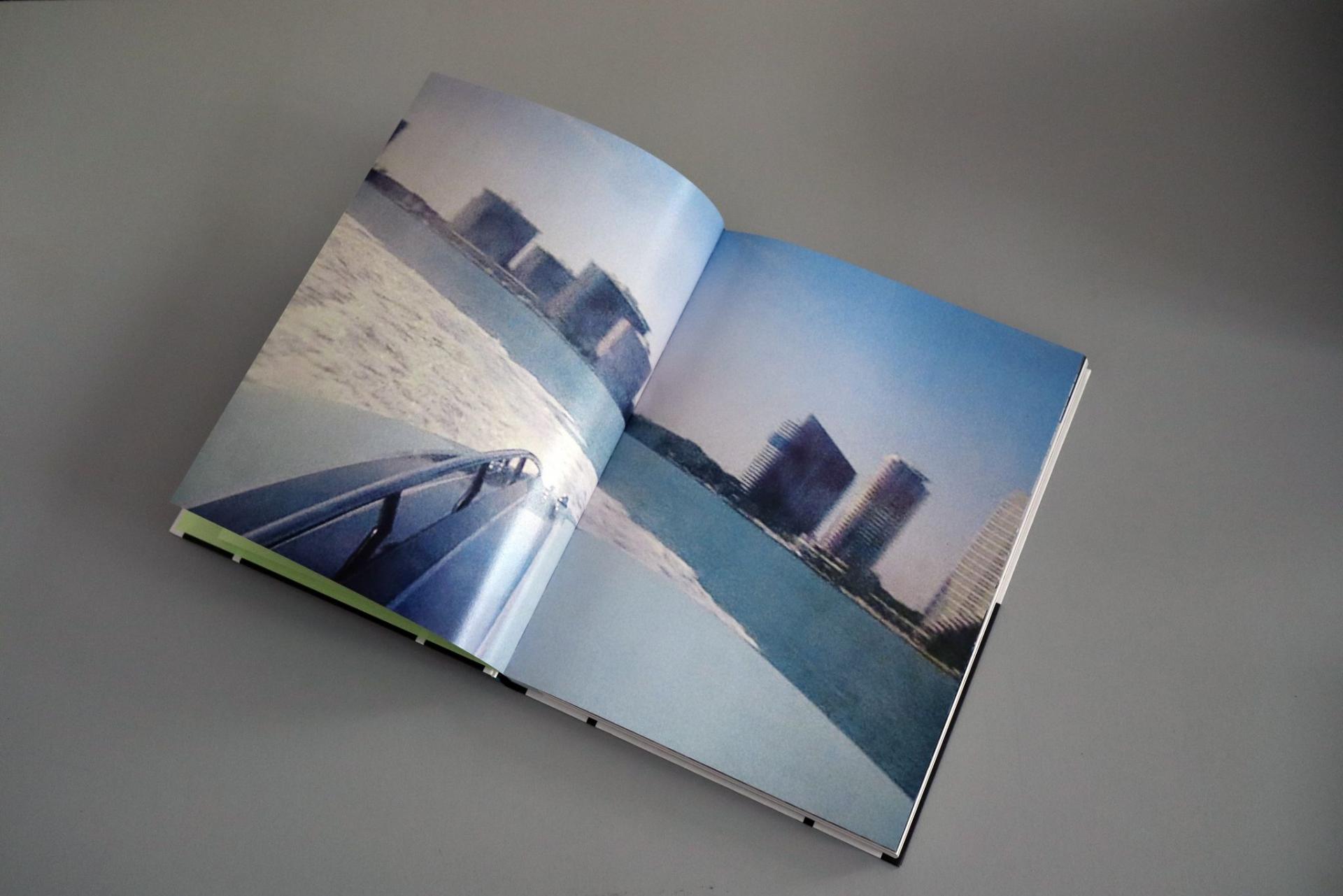

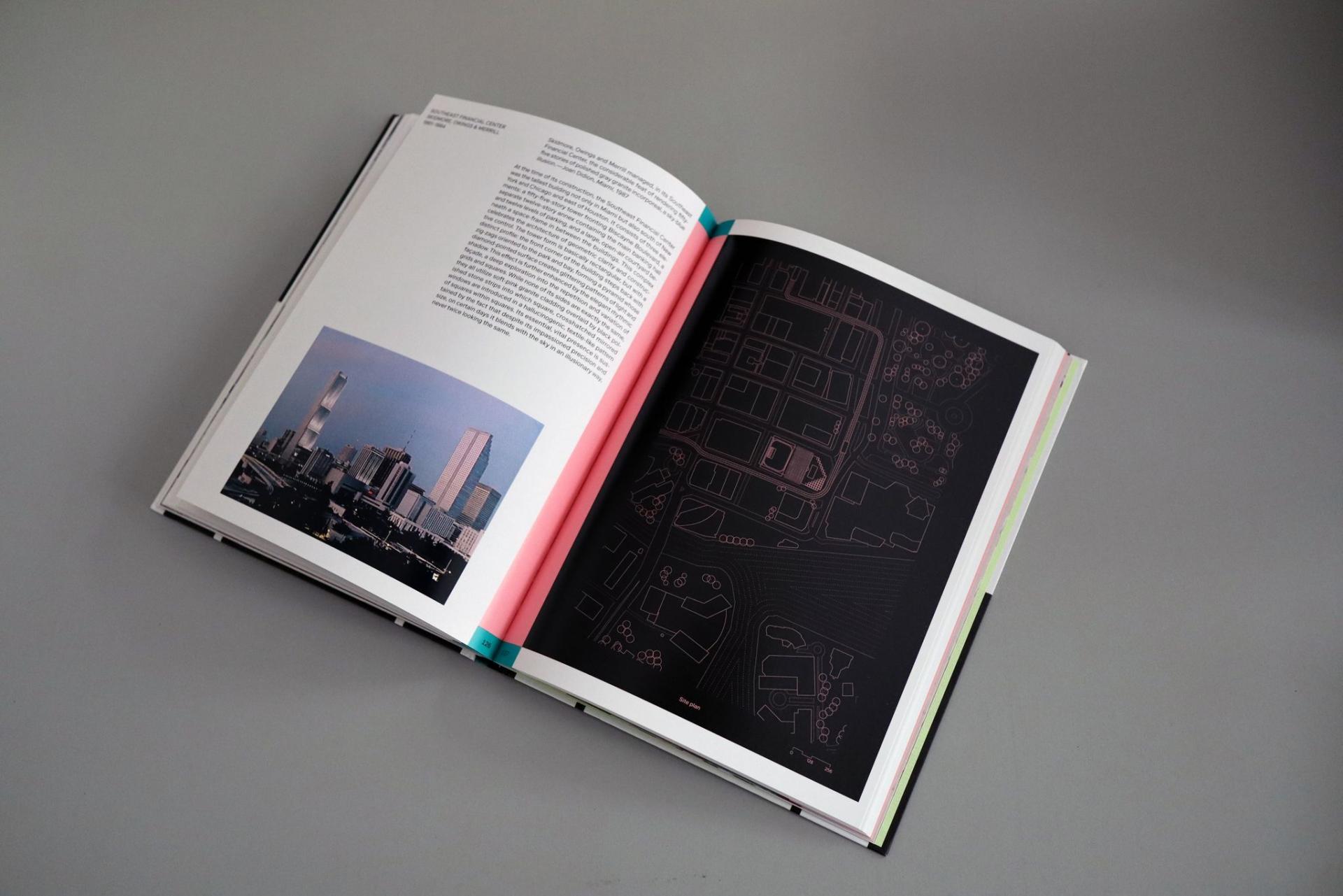

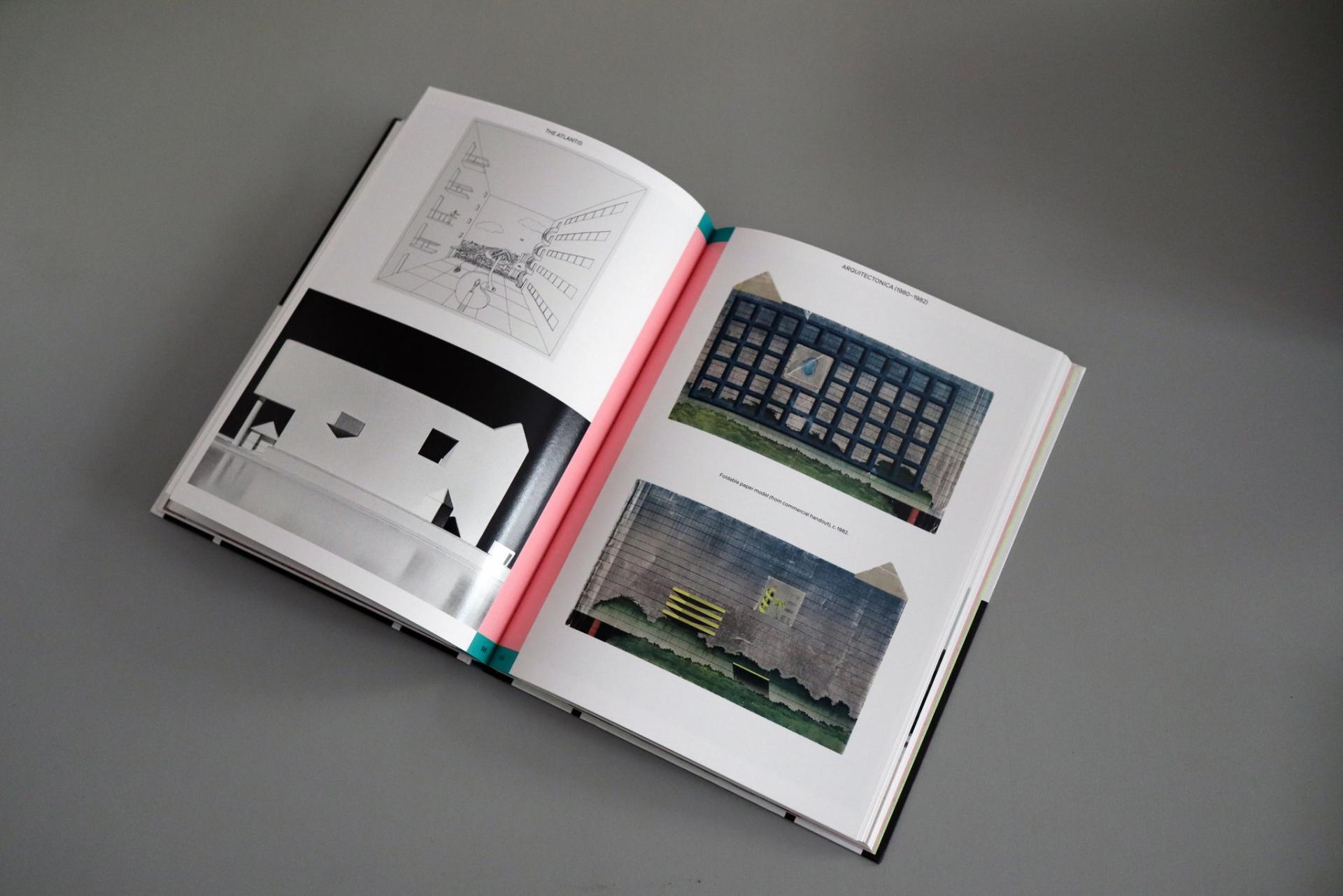

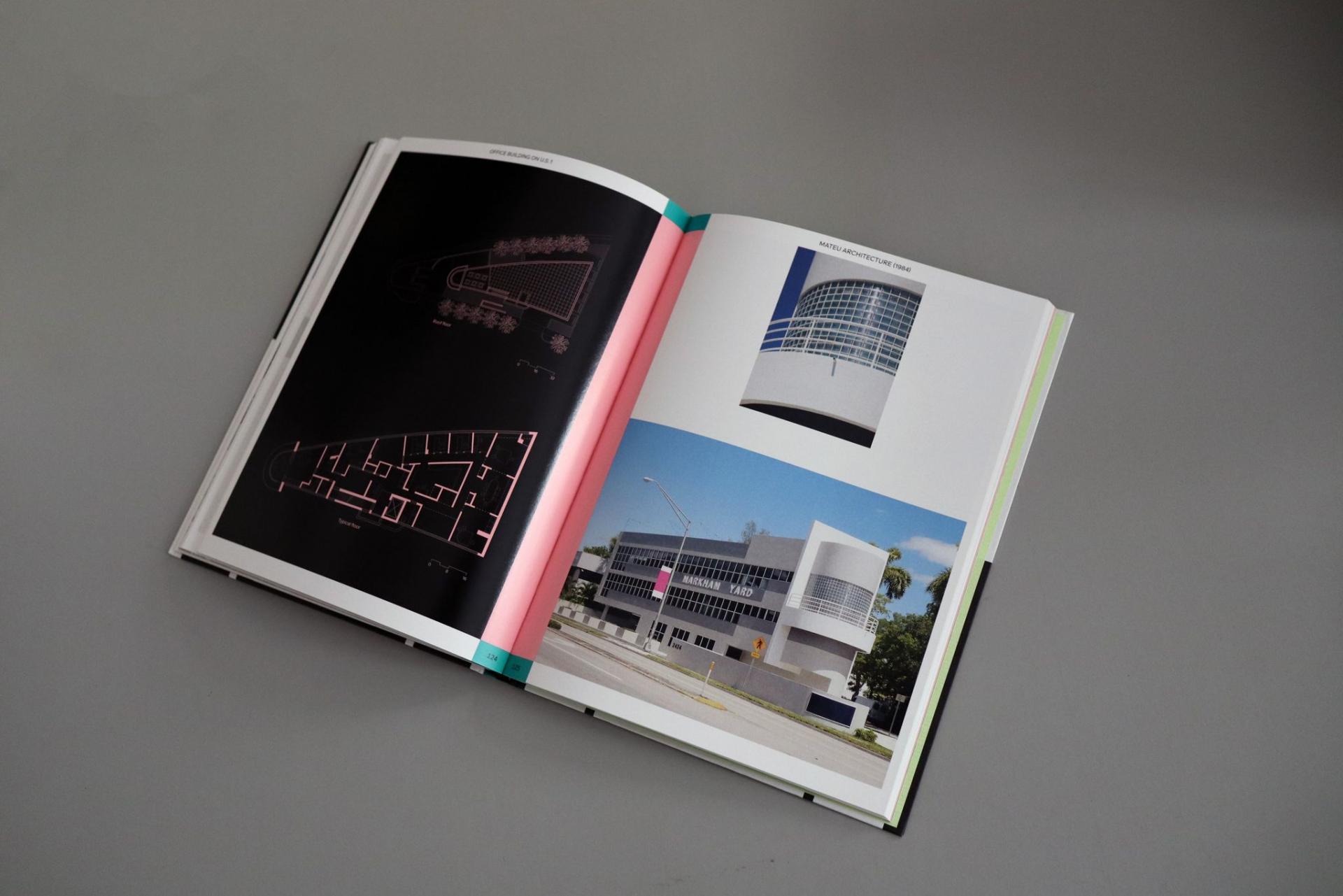

The in-depth essay is followed by short introductions with archival or new photographs (and drawings) of 19 projects made my S.O.M, Philip Johnson & John Burgee, Mateu Architecture, Duany Plater-Zyberk, Isamu Noguchi and – of course – Arquitectonica. It’s like eating a pistachio, raspberry, mint and vanilla ice cream: you know you shouldn’t like it and that it’s gonna make you sick, but you cannot stop. Still, and that’s probably the goal of the book: many of those buildings are now in danger – the taste of the inhabitants has changed, downtown Miami craves for densification and the constructions are too young to become historical monuments (think about the IBA87 in Berlin). A whole visual chapter is allocated to the demolition of The Babylon (1981) by Arquitectonica, and alerts us that it might be our last chance to visit those buildings believing we are undercover cops driving a white Ferrari.

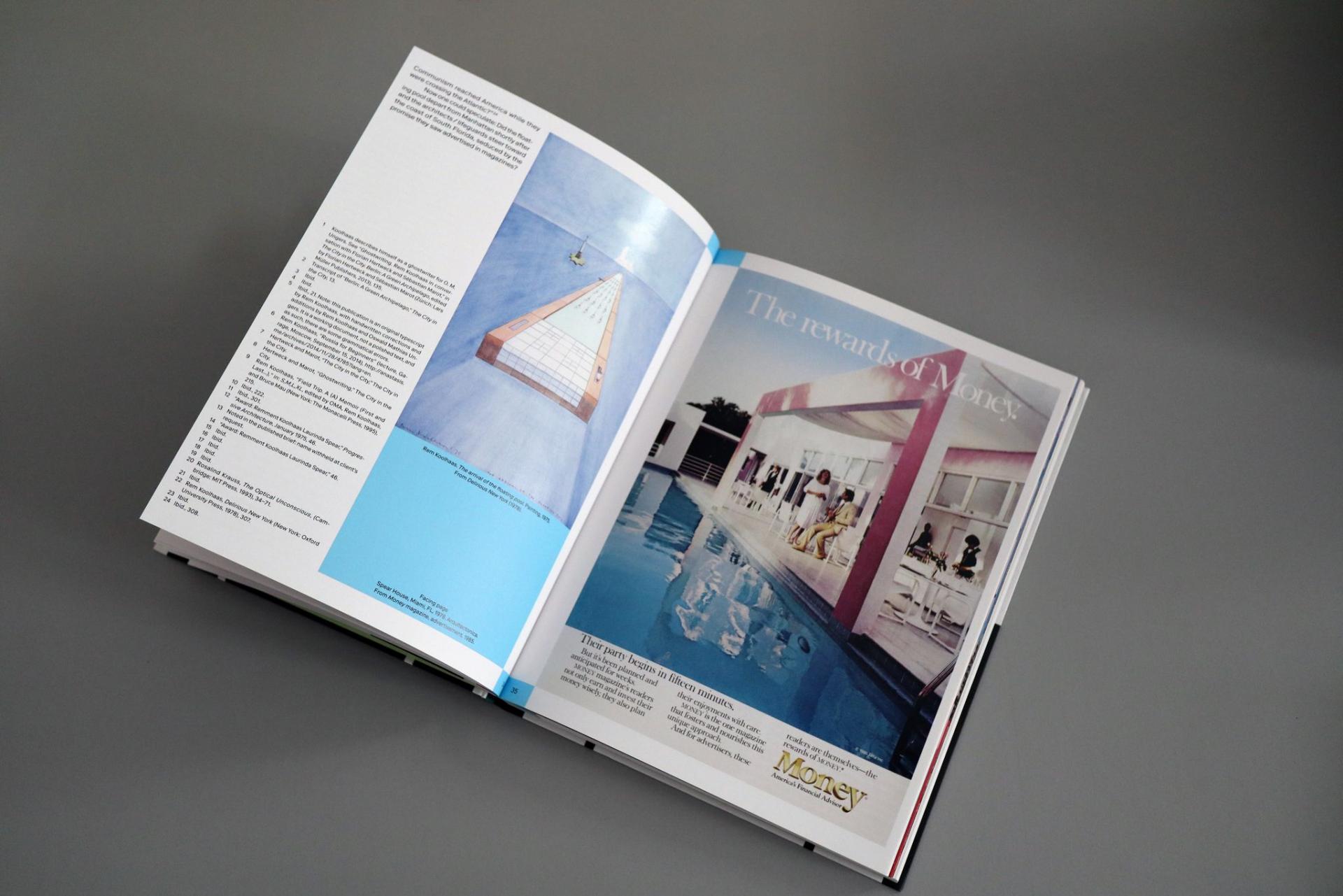

Now comes a spoiler, like in movies, but I’m gonna tell you how the book ends (so stop reading here if you don’t want to know)… The final spreads are dedicated to fashion shoots that were done in the Spear House for GQ or Vogue. The legs of a lady in a bikini enjoy the swimming pool, a young man in pyjama stares into our eyes, other people sunbath on the terrace or jump into the water. They pose with their perfectly clean clothes and rather impossible haircuts (too much hairspray involved, much too much – but that’s the 1980s). What becomes clear, looking at those images, is that architecture – here, is more than a decor. It’s a part of a lifestyle that includes nice cars, expensive watches and shiny garments, making the American dream a kitsch and unattainable Gesamtkunstwerk. A total work of art.