Seoul Reflections

Final spurt for the inaugural Seoul Biennial of Architecture and Urbanism which will close on November 5th and time for an appraisal by Jason Hilgefort who participated in the event (Disclosure: as did Christian Burkhard, this website’s Editor in Chief). But here is Jason:

Zaha Hadid’s DDP, the venue for the Biennale’s Cities Exhibition

To start off it must be stated that the Seoul Biennale is extremely impressive in its shear ambition. For a first time biennale its scope, goals, vision, actions upon the city, attempt to engage citizens is wildly far reaching. This is in part a credit to its currently governmental realities. The city itself has recently put in motion a series of very large gestures throughout its urban landscape and this is just its latest project on/in the city.

Playing the city (in Zaha Hadid’s DDP)

In relation to these governmental goals, the site selection itself is of note. The ‘exhibition’ was spread into three ‘sites’ throughout the city. Perhaps the most obvious and iconic space is the Cities Exhibition, which was located within the Zaha Hadid designed Dongdaemun Design Plaza [DDP] – curated by Helen Hejung Choi. With a twisting, ramping space wrapping around a central open void that was subdivided into a bazaar-like marketplace of ideas, the spatial experience was memorable to say the least. And it was an astute curatorial solution to the non-standard, challenging formal reality of the venue. The whole of the looping series of quick hit installations along the swooping ramp in many ways stood out spatially.

Exhibits on the ramp of the DDP in the Cities Exhbition

However it was the exhibition on Pyongyang, North Korea by Dongwoo Yim and Calvin Chua stole the show. The painstakingly recreated one to one installation of the reality of an apartment in the communist city alongside the series of drawings, statistics, and a ‘make your own catalogue’ elements scattered throughout were a showstopper.

Cities Exhibition on Pyongyang, North Korea

Yet quietly the goal of having often ‘non design’ teams set up exhibitions in the space, each on their own city was the true innovation. Seeing each city tell a story from not just architects or design teams gave a diversity and depth of voices to the exhibition often not seen in international biennales.

In contrast, the Donuimun Museum Village was an illustration of adapting a historic quarter in the city to host an international event. And a further differentiation, this vision for ‘The Nine Commons’ (the title of the Biennale’s Thematic Exhibition) focused much more on the technical elements of our built world – featuring the likes of Beatriz Colomina, Philippe Rahm, Tomás Saraceno, and many more dealing with matters like air, fire, and social media.

Impressions from the Thematic Exhibition at Donuimun Museum Village

Although there were many eye catching installs [Beyond Mining Urban Growth by Dirk E. Hebel, Philippe Block mushroom-tastic layered installation must be commended], the one that sticks in my mind is the ’Driverless Vision’ by Urtzi Grau, Guillermo Fernández-Abascal, Daniel Perlin, and Maximilian Lauter.

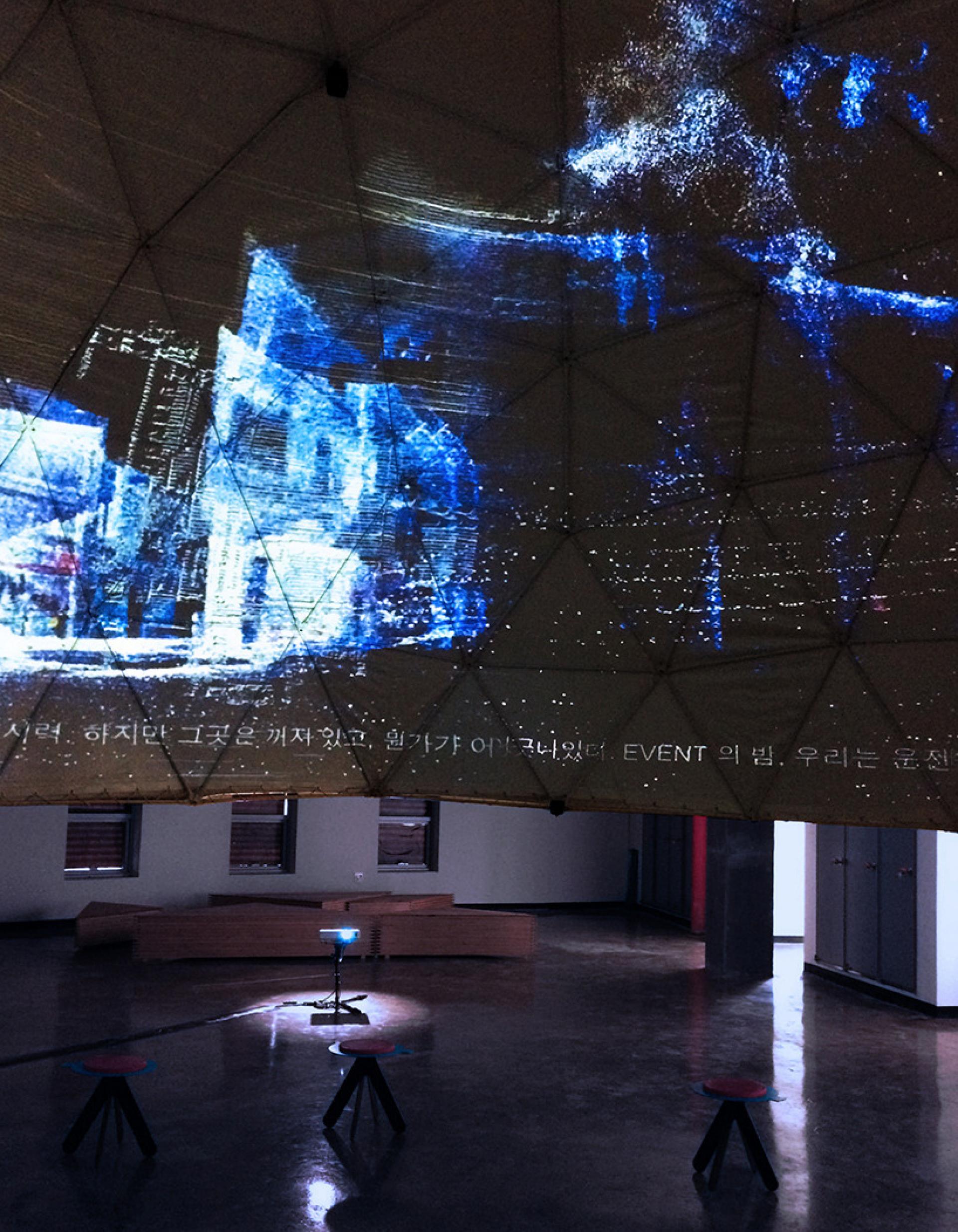

Driverless Vision exhibit at the Seoul Biennale

It stepped beyond the idea of merely self-driving cars into a hauntingly beautiful dystopian possible future with autonomous vehicles roaming a human-less city; oddly managing to humanise a technical future by removing the humans.

Broadly, much can be said for the value of taking on the hot topic of commons in the current professional discourse and expanding upon it. However, one can also suggest that the exhibition dilutes the topic to be almost everything and perhaps gets lost in the technical implications of a theme that would have been a more ideal medium for engaging the public in urban/architectural issues.

“Do We Dream Under The Same Sky”, exhibit at the Thematic Exhibition

The two main sites (DDP and Museum Village) sit to the east and west of the city centre, in respect to western and eastern historical narratives of the city; as well speak to contemporary global and historical local languages through the built forms of each site. This juggling of new and old is well executed and adds a multi-layered quality to the ideas put forward. But perhaps the most provocative of all was the ‘third site[s]’ of the Live Projects locations, in addition to the looooong and impressive list of public programs throughout the city [tours, forums, films, libraries, international architecture studious, etc]. For myself, the most relevant and more visually iconic of all spaces was the ‘Productive City’ within the Sewoon Sanga mega structure.

The site of Sewoon Sangga with a view to the mountains in the north

This part of the exhibition was an engagement with the existing aging building sitting amidst a on-the-verge-of-changing mixed use industrial area. It was more of an architectural programmatic operation used as a tool for framing a discussion in society. It represents a local action in the city itself and not merely an exhibition of internationally provocative ideas.

Mixed use small scale industrial area next to Sewoon Sangga

Its efficacy will only be able to be judged in the long run, but it relates to similar curatorial goals in the perhaps other most internationally well-known architecture/urbanism biennale in Asia – the Shenzhen/Hong Kong Biennale [of note: the author was a sub-curator]. Because these cities are moving so rapidly, or maybe because they have learned from the ‘showcase’ nature of Venice and other events – they seek to use these exhibitions as a method to work upon and open up the doors for a discourse about the city and the challenges it is facing. Each looks distantly abroad, yet simultaneously zooms in to enable local action.

In closing, I must share an off-the-cuff comment from a friend that still rings in my ear. For all of its far reaching agendas - from international to local, from technical to metropolitan – there exists a gap in the ‘middle’. This biennale of architecture and urbanism doesn’t have much ‘architecture’. In many ways the buildings chosen to exhibit within were the strongest architectural elements [Zaha, old village, modernist mega structure], but were merely the backdrop or frames to the issues explored. It is tough to draw conclusions about what this says about the biennale, Seoul, or the state of our cities. But this void does seem to echo a common passivity toward the discussion of buildings themselves within the profession of architecture. The complexity and possibilities of technology and our cities are alluring and exciting, but perhaps in the pursuit of the ‘interesting’ we miss the tangibility of ‘just a building’ and how it speaks to layered issues of the world today.

- Jason Hilgefort

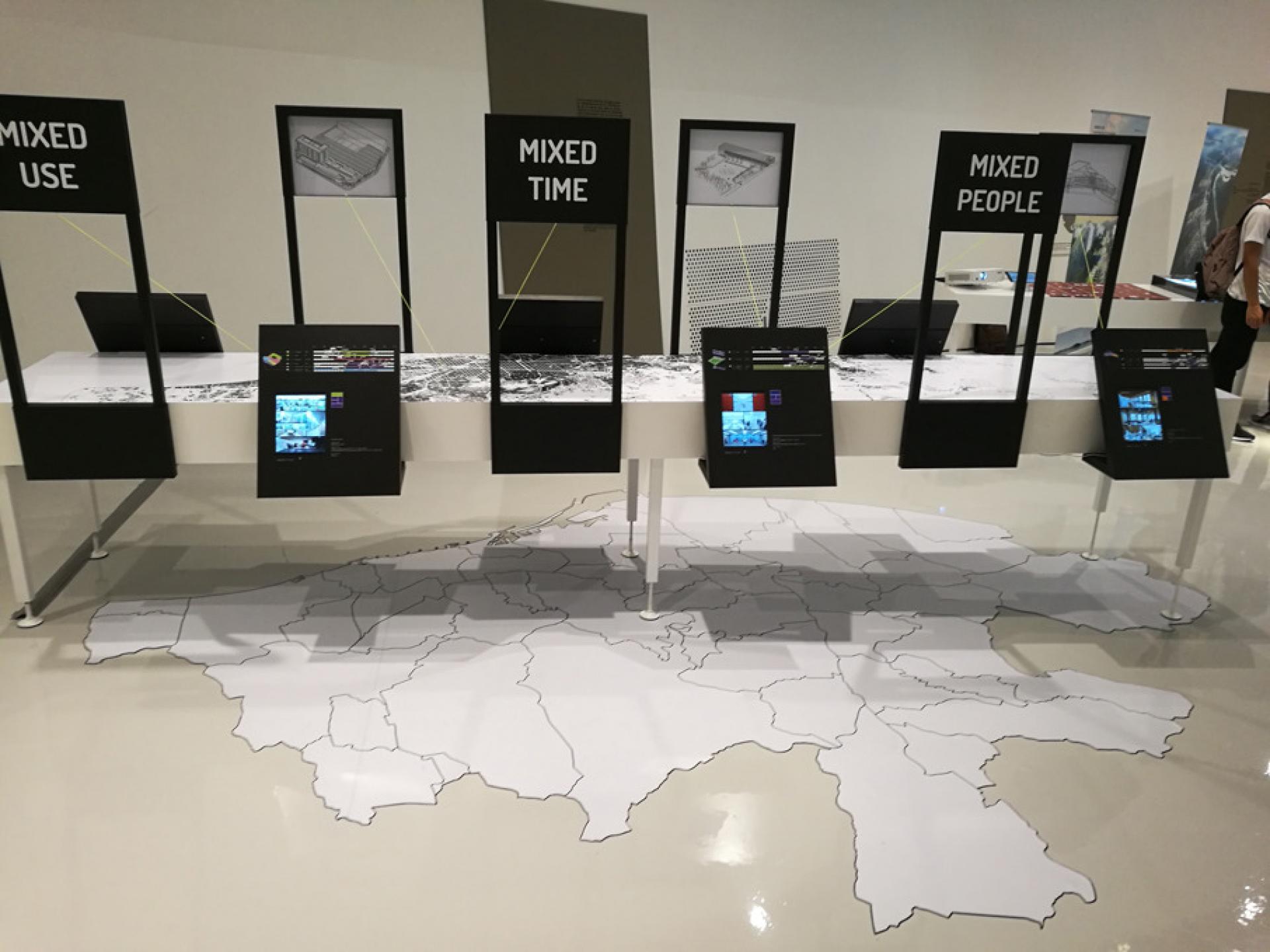

Some projects featured on the ramp of the DDP at the Cities exhibition:

Barcelona: Mixed Use, Mixed Time, Mixed People. Barcelona Metropolitan Area (AMB) & Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC)

Cities in China: Ghost Cities. Sarah Williams, Civic Data Design Lab, MIT

Berlin: Die Laube. Quest (Christian Burkhard, Florian Köhl)

Macao: Shaped By Use. Nuno Soares, Filipa Simões

Shenzhen: Shenzhen to PRD (Pearl River Delta) Method. Future+ Aformal Academy (Jason Hilgefort, Merve Bedir)