Pioneer Architects II

It’s time again to meet five women which left their magnificent outputs and have no credits for their work in architecture. Second edition of Pioneer Architects presents Eilien Gray (Ireland, 1878-1976), Jane Drew (United Kingdom, 1911-1996), Jane Jacobs (USA/ Canada, 1916-2006), Marion Mahony Griffin (USA, 1871-1960) and Norma Sklarek (USA, 1926-2012).

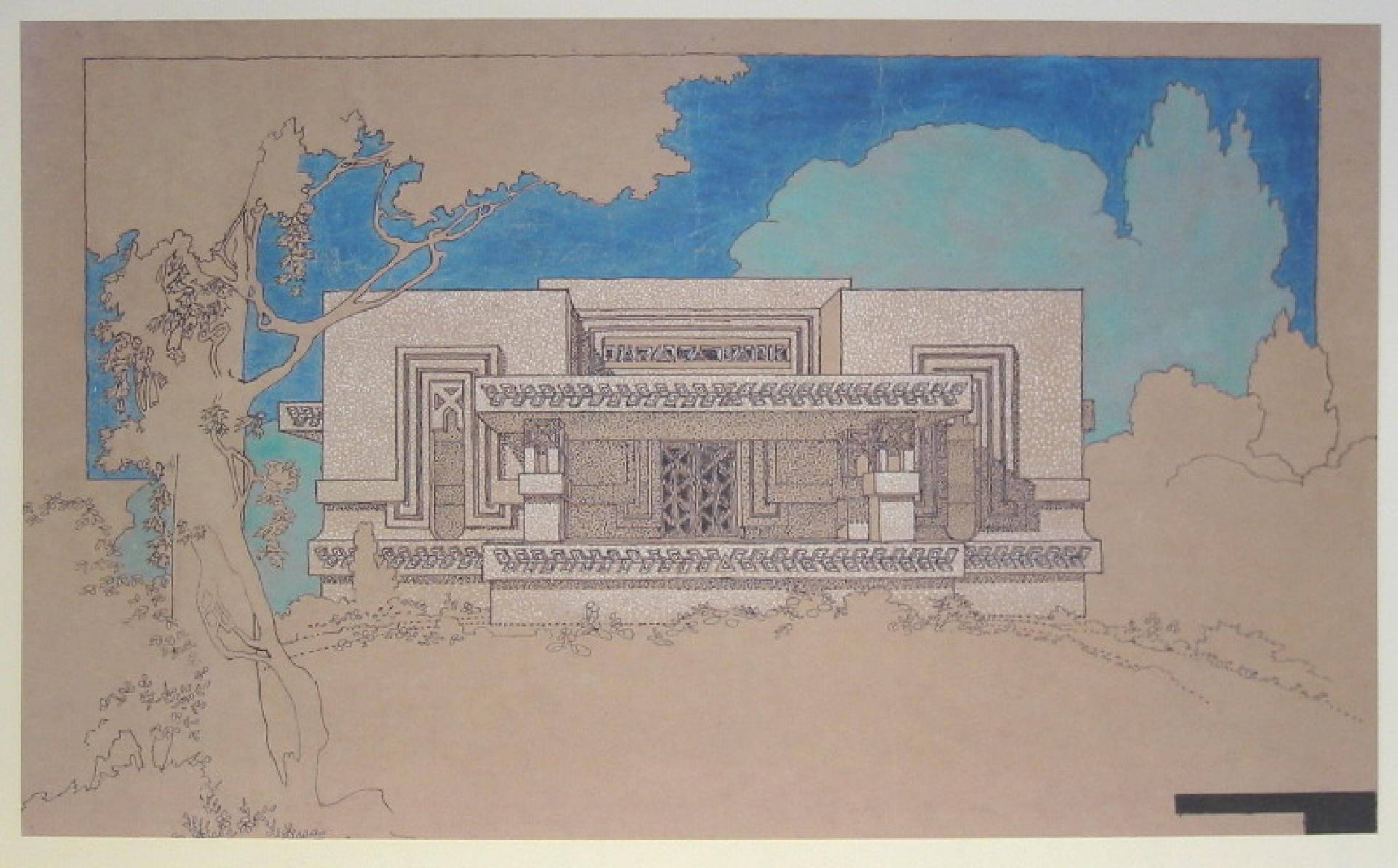

Mahony Griffin was the first employee of Frank Lloyd Wright in 1895. | Photo via Architectural Record

Marion Mahony Griffin was one of the first licensed female architects in the world. She graduated at MIT in 1894. Mahoney exerted a considerable influence on the development of the Prairie style, while her watercolor renderings soon became synonymous of Wright’s work. As was typical for Frank Lloyd Wright at the time, he didn’t credited her. Their collaboration ended in 1909 when Wright left for Europe, offering to leave the studio’s commissions to Mahony. She declined.

Architectural aquarel by Marion Mahony Griffin. | Photo via Alchetron

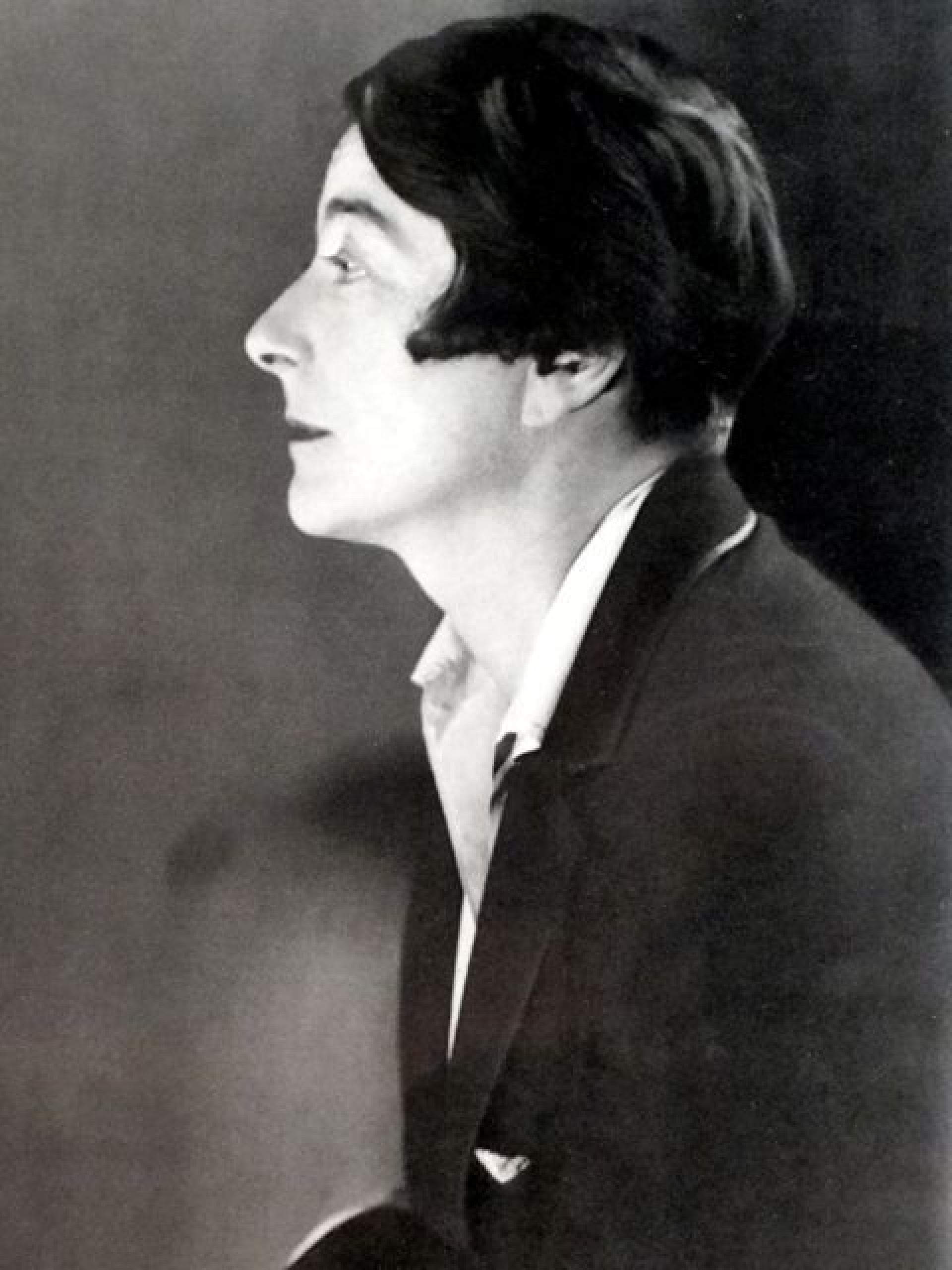

An Irish furniture designer and architect Eileen Gray was a pioneer of the Modern Movement in architecture. She was the first women recognized for her work in industrial design. At the outbreak of World War I, Eileen was driving an ambulance in Paris. Later she returned to London and open a workshop for furniture design in Chealsea. She earned a reputation of a first European artist which adapt the Asian traditional techniques in 1922. For Gray a house was not just a machine to live in but “the shell of man - his extension, his release, his spiritual emanation.“

Le Corbusier was a fervent admirer of architecture of Gray. | Photo via Skelton

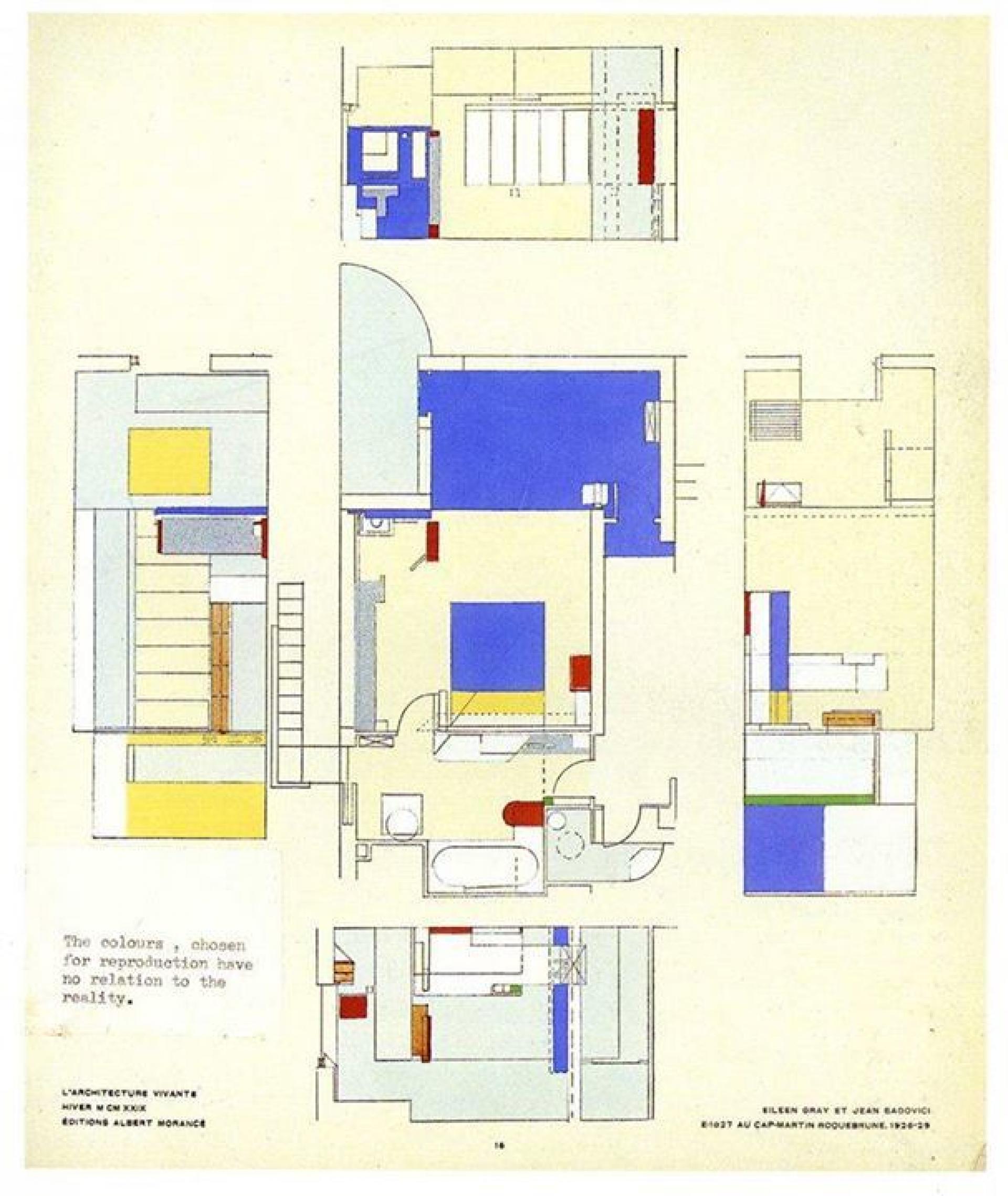

Gray began experimenting with architecture since 1926, when he became a collaborator of the Romanian architect Jean Badovici (1893-1956). Her most known house is E 1027.

Eileen Gray’s plan of E-1027. | Photo via Agent of Style

Jane Drew was an English modernist architect and town planner working in the United Kingdom, Africa, Iran and India. She received her qualifications at the AA School in London. Shortly after her studies she became involved in the Modern Movement, through the Congres International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM). Drew became one of the principal founders of the Modern Movement in Britain, which was represented by MARS (Modern Architectural ReSearch), an association of architects and painters with stated principle of "use of space for human activity rather than the manipulation of stylized convention.”

Jane Drew has met Henry Moore, Elizabeth Lutyens and her husband Maxwell Fry through the movement MARS. | Photo by Jorge Lewinski

Secondary School Entrance in Chandigarh (1951-53) was designed by Jane Drew. | Photo via WIA

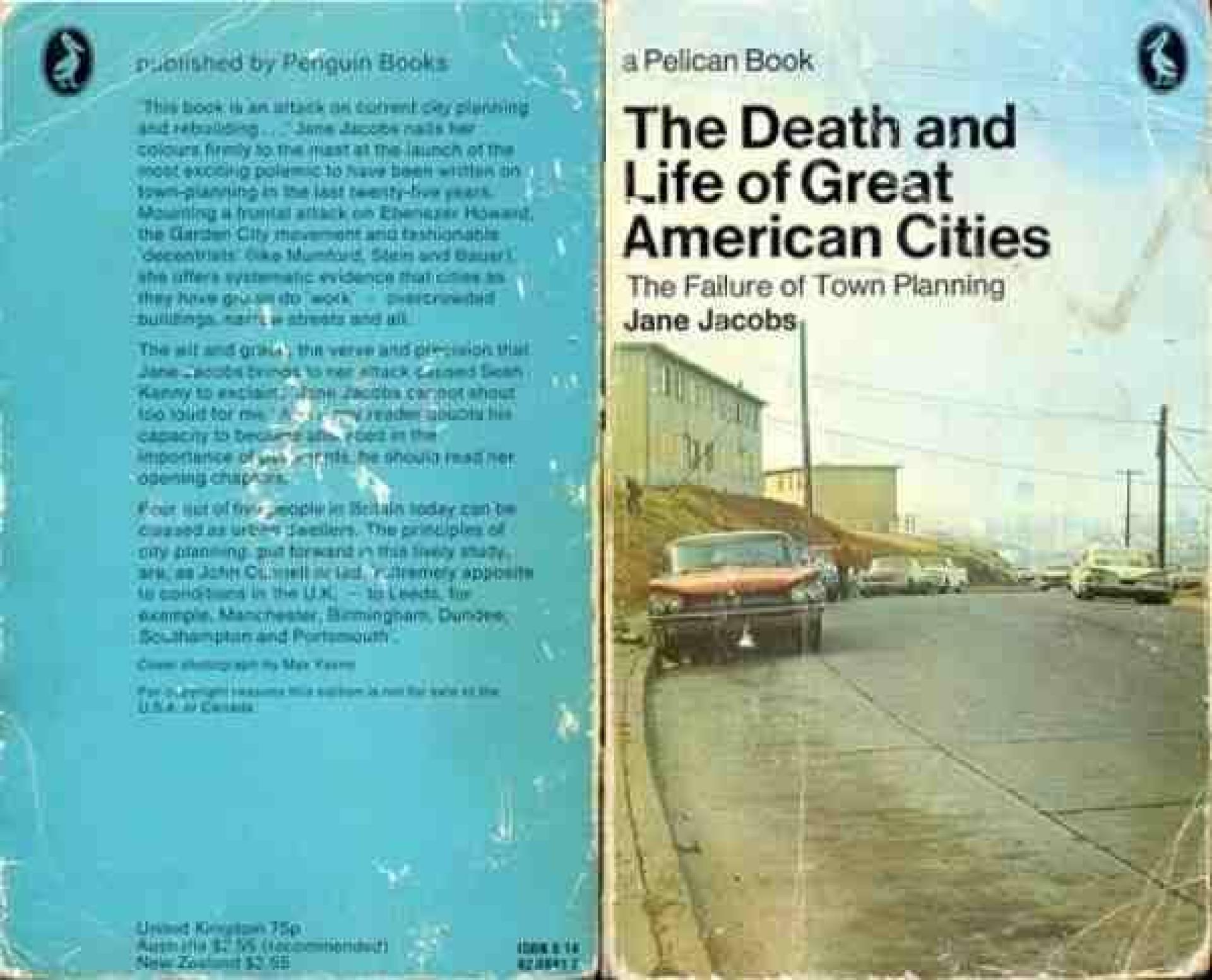

A writer and activist Jane Jacobs with primary interest in communities and urban planning is best known for her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). This powerful critique of the urban renewal policies of the 1950s in the United States has been credited with reaching beyond planning issues to influence the spirit of the times.

“Citizen Jane” was known for organizing grassroots efforts to block urban-renewal projects that would have destroyed local neighborhoods. | Photo by Fred W. McDarrah/ Getty Images

In 1968, Jacobs moved to Toronto. She decided to leave the United States because of her objection to the Vietnam War. She quickly became a leading figure in her new city. A frequent theme of her work was to ask whether we are building cities for people or for cars.

The critique of the urban renewal policies of the 1950s in the United States; writed architecture by Jane Jacobs. | Photo via Architecture and Urbanism

Norma Sklarek was the first licensed African-American female architect and the first black female fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1962. After a year at Barnard College she enrolled at Columbia University’s School of Architecture, an accomplishment all on its own considering that Columbia only accepted a handful of women each year. In 1954 she become one of the first African American women to be a licensed architect in the U.S.A.

Sklarek was unable to find a position with an architecture firm, so she went to work for the New York Department of Public Works. | Photo via Inc

Sklarek’s best known project is renovation of Terminal One at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX).

Much has changed since Sklarek first started working. Of the nearly 250,000 working architects in the U.S., nearly 10,000 of them are African-American. For obvious reasons, Sklarek has helped foster that change both as an example, and through her own direct efforts to make a difference. In 1990 she became the only black woman elected to the American Institute of Architecture (AIA) College of Fellows.