Emblem Of A Better Germany?

It was a black Mercedes-Benz car with its famous star that added the air of a different era, the Federal Republic of Germany before the fall of the Wall, when its capital was Bonn on the Rhine River in West Germany, and not Berlin. Placed before the steps of the monumental façade of the German pavilion, once build as the Bavarian pavilion and then decisively altered by Nazi Germany in 1938, every German visitor would read this car as a sign, an emblem of what came to be known as “Made in Germany”, high quality cars, machines, and other industrial goods that were seen as responsible for the so-called “Wirtschaftswunder” (economic miracle) after WWII, the economic rebuilding of West Germany.

On the one hand, this car is a desirable object, vintage and expensive. In my family, you knew you had made it when you could afford a Mercedes-Benz. You could tell, when my parents bought their first Mercedes-Benz, they were full of pride. And they still drive the same car and feel the same way about it, although now it’s a rather old car.

On the other hand, you could also read the continuities of 20th century German history into this juxtaposition of car and pavilion. Because what is the link between the Nazi façade and the later car? You might answer this question with the seamless integration of Nazis in German politics and business and the financial gains of many German companies (including Daimler-Benz) during the Nazi period thanks to forced labor, expropriation, and simple opportunism. The juxtaposition places you, at least as a German, between guilt and pride, haunting memories and desire.

Adjacent to the left of the big front door of the German pavilion in Venice, the visitor was greeted by an elegant section of a roof jutting out above a much smaller door. It was a hint that the interior of the pavilion was taken over by another structure, a partial replica of the former Chancellor’s residence in the former capital of the country formerly known as West Germany. A somewhat nostalgic remnant of a bygone past, a country and political system that were fundamentally altered by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany. It was the Germany I was born into, with Bonn being the capital until 1999 and the Chancellor’s residence – or Kanzlerbungalow (‘Chancellor’s bungalow’) – constantly in the news. As much as it was nostalgic, Lehnerer and Ciriacidis’ pavilion had an uncanny feeling to it. Inside and outside were suddenly called into question, different times collapsed into each other, with the democratic bungalow inserted into the Nazi pavilion. Or was the story told more complex than that, as with the car parked in front of the pavilion? The story was, for sure, one about architectural representation.

The Chancellor’s bungalow was built in 1964 by the architect Sep Ruf for Ludwig Erhard, the second Chancellor of West Germany. Erhard was the German politician who stood like no other for the ‘economic miracle’ of West Germany after WWII. As the Federal Minister of Economic Affairs under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer from 1949 until 1963, when he became Chancellor himself for three rather unlucky years, he promoted what he termed the social market economy and gained widespread popularity with this economic concept. Although Erhard worked for the German state as an economist during the war, he rejected Nazism and was in contact with members of German resistance groups. It seems fitting therefore that as Chancellor he hired the fellow Bavarian Sep Ruf to design the new Chancellors residence in Bonn. Ruf was known for his functional designs in the tradition of the Bauhaus and older modern architects, who had mostly emigrated during the 1930s, likeLudwig Mies van der Rohe. Ruf’s elegant bungalow in Bonn payed homage to designs of the Bauhaus and Mies in particular. The latter’s Barcelona Pavilion, the German Pavilion at the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, has often been mentioned as a reference.

Dining room of the bungalow of the Chancellor in Bonn.

By 1964, Ruf had already worked for the federal government several times. Together with another modernist architect of the postwar period, Egon Eiermann, he had for example built the German pavilion for the world fair in Brussels in 1958. He was, thus, well informed about West Germany’s representational needs. The Chancellor’s bungalow spoke not only of the Bauhaus and the better, modern Germany that was supposed to be represented by buildings in its tradition like those of Ruf, Eiermann and others, but it also established a clear link to modern architecture internationally. Looking at the bungalow, some might be reminded of the famous Case Study Houses at the West Coast of the USA. After all, it was the declared aim of West German politicians to make the Federal Republic part of the Western political sphere (‘Westbindung’, or policy of the alignment with the West). I would guess that these two aspects, the tradition of a better, modern Germany and the alignment with the West, were first and foremost represented by Ruf’s bungalow in Bonn.

The second Chancellor of Germany, Ludwig Erhard.

The third Chancellor, Kurt Georg Kiesinger, took over from Ludwig Erhard in 1966. He was a former member of the NSDAP and disliked the Chancellor’s bungalow for its functional, ‘cold’ design. He had many things altered before he moved in and brought with him antique furniture pieces in stark contrast with Ruf’s modern architecture. Most of the other Chancellor’s after him agreed with Kiesinger’s view on their official residence. They were looking for something more comfortable and cosy (gemütlich). Under Chancellor Helmut Kohl the interiors had changed so fundamentally that it was hard to still see Ruf’s designs behind thick layers of carpet and bulky sofas and chairs. Not to speak of the new 1980s glittery lighting. Although partly preserved in the original building in Bonn, these alterations, additions and layers were not present in Venice.

Prince Philip, Queen Elizabeth II and the ex-Chancellor of Germany Helmut Kohl front of the bungalow of the Chancellor in Bonn.

It was a clearer picture or juxtaposition that Lehnerer and Ciriacidis drew. Only the brief blaze of fire in the Chancellor’s fireplace could have been something of a reminiscence to the other, the not-so-modern, not-so-open, cosy Germany that gathered around home-and-hearth. The Germany I grew up in. Just like the Mercedes-Benz, a fireplace was something quite desirable for the generation of my parents. You had to have one. And now, decades later, my parents even installed a new one. As if you couldn’t or wouldn’t want to live without it. Herman Miller’s Eames Collection that Erhard chose for his initial version of the bungalow at the River Rhine might have always been too expensive for most Germans, but they also represented a certain idea of Germany, like the whole bungalow an internationally oriented, better Germany – and not necessarily the real one. I wonder, does the real, and not the ideal, ever get represented? It might be an interesting task for a future German pavilion at the VAB.

The bungalow of the Chancellor in Bonn.

West Germany claimed the Bauhaus as its heritage since the 1950s, through the founding of the Bauhaus-Archiv in Darmstadt in 1960, countless exhibitions and books and buildings seemingly in its tradition (there were similar efforts in the GDR a little later). 2019, the year of the centenary of its founding, saw the Bauhaus at the height of its representational instrumentalization, it had become a major part of German cultural diplomacy. Yet, the Bauhaus has oscillated between national claims and International Style even before it was closed by the Nazis. This oscillating reception of the Bauhaus was crucial in making sure that the Bauhaus would continue to be productive until today. Looking back in 2020, the German Pavilion at the 14th VAB is also a vivid illustration of the complicated history of the Bauhaus and Germany.

The Invisible Church

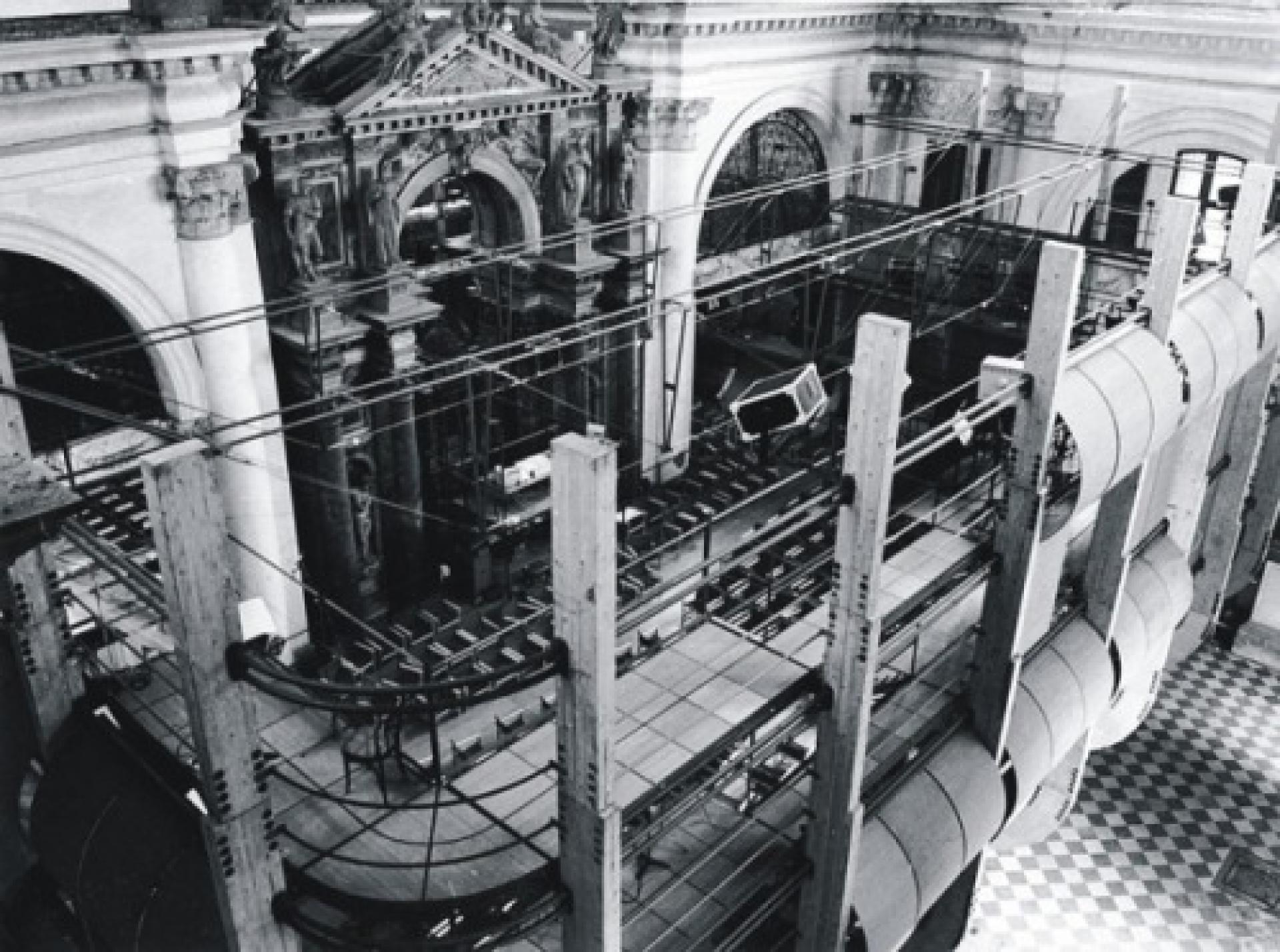

The structure designed by Renzo Piano on that evening occupied it all; a maze of scaffolding, where to navigate it was to play a role in it, and a brief description of the “huge musical instrument and sounding board that housed the stage, audience and orchestra” to be seen from the seats at the center of that all-encompassing stage.

Music Space for Prometeo Opera by Renzo Piano Architects (1984), San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Fondazione Renzo Piano

Music Space for Prometeo Opera Section Drawing by Renzo Piano Architects (1984), San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Fondazione Renzo Piano

Everything was ruddy, shadowy, and indistinct. Even more so when they had just lit up the stage and my eyes were dazzled, and I was barely able to see that enormous door wide open, through the vast and incredible hole that swallowed the whole of the lower portion of the altarpiece.

Music Space for Prometeo Opera by Renzo Piano Architects (1984), San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Fondazione Renzo Piano

The musicians positioned themselves along the staircase, the lights dimmed and Prometheus began to fill the room with its flame, in a musical conversation between the wooden panels, the omnipresent scaffold and the hidden walls of the church.

Prometeo Opera Musicians Rehearsal (1984) in San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Fondazione Renzo Piano

I like to believe the music made her visible for a moment and I was able to see her face —even if covered— for the night.

Prometeo Opera Opening Night (1984), San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Fondazione Renzo Piano

Maybe it was just the illusion of wanting to see her real face. Maybe it was the face of Prometheus before the doors of light and thunder closed again.

“Black here and white there-in patches. She’s a kind of half-breed, and the colors come off patchy in places instead of mixing. I’ve heard of such things before. And it’s the common way with these venues, as anyone can see.” The reality is that the church was invisible. She had always been. Piano and Nono’s imagination created a place that fitted in with what they thought they knew about her glaring real absence. They dressed her in masks, clothes and artifices for her to become them in time. In this little church, form was background. What we witnessed there was not a mere representation of Prometheus; it was Prometheus. Beyond the brief moments that her stolen radiance lasted, she would stay only Prometheus. For the more they included her in the conversation, the more invisible she was to all the present. The church was silent and nodding, and those were her best qualities; a magnificent vision of what real invisibility means —the mystery, the power, the freedom, the licentiousness— where they saw no inconvenience in disposing of the helpless building. They arrived at the conclusion that a destitute church could become the manifestation of anything.

Twenty-eight years elapsed since the Italian music and pyrotechnics, when the Mexicans arrived with their ideas for promoting folklore.

Culture Under Construction - The Collectivity of Cultural Space Installation Photo Montage 2012, San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Arquine

The same biennial, the same pretensions, the same assumptions, the same scaffold, that now covered her from the outside; new brighter and more colorful banners fluttered in the Venetian summer breeze laying over the church once more.

Culture Under Construction - The Collectivity of Cultural Space Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2012, San Lorenzo Church, Venice | Archdaily

The gesture stood as a true triumph of artifice over reality, choosing the most crowded moments of its square to show the cultural power of a distant country, which found itself eagerly seeking to show its appreciation for the ruin, preservation and millennial constructive capacities. They decided to elevate the scaffold and extended it to the façade —as the Italians had done in their time to her interior— covering the church’s entrance in its entirety with a pompous mask.

With some ingenuity, imagination, but above all money, she assured them a visible place at the Biennale at the cost of her own. But pacts are easy to break, especially if they are written on air and promised from afar. They would soon realize the terrible contradiction: after the frantic gestures to recover the church by Mexico —which surprised more than one— the headlong pace after the summer that swept her away, the inhuman bludgeoning of all the tentative advances of curiosity, the taste for winter that led to the closing of doors, the pulling down of blinds, the extinction of candles and lamps after the party, the church was still empty.

San Lorenzo Church Interior 2012, San Lorenzo Church, Venice, Italy | Arquine

She disappeared for a while, but with the return of the Biennale-eaggered tourists that the summer brings, so did the scaffolding, this time to cover the wounds underneath Ariel Gusizk’s Cordiox.

The inner emptiness was of absolute clarity; her invisibility transcended the concealment of her ordinary face. The Church for the first time was half-bare, and yet, the only thing we could —we wanted— see were her improvised clothes. Those scaffolds that had already become the building; whether to cover its altars, its ceilings, its facades, or its wounds, allowing us to see in time those transitory garments that, by opposition, had turned her into a mystery, a wrapped caricature, a silhouette. She would appear and disappear with the Biennale, but no one would notice or care anymore, so they cut her loose. When they removed the scaffold, banners and the lights, they only verified what we already knew. She had long been gone.